A freelance art researcher based in New York, Delphine Huisinga has been working closely with the Gagosian publications team on a series of ongoing projects for the past five years. She was also the researcher for the fourth volume of John Richardson’s Life of Picasso. Photo: Pamela Berkovic

Alison McDonald is the Chief Creative Officer at Gagosian and has overseen marketing and publications at the gallery since 2002. During her tenure she has worked closely with Larry Gagosian to shape every aspect of the gallery’s extensive publishing program and has personally overseen more than five hundred books dedicated to the gallery’s artists. In 2020, McDonald was included in the Observer’s Arts Power 50.

Larry Gagosian has played a fundamental role in shaping the art world of our time. Much has been made of his ambition, instincts, and perseverance right from the beginning of his career: he took risks, always worked with the best artists he could, and established connections between important East Coast artists and West Coast collectors; and he supported performance art, Conceptual art, and photography, all three of which were having pivotal moments in the 1970s, when he started out. This essay shines new light on some of the key moments of his early career, specifically between 1972 and 1977.

The date most often given as the beginning of Larry’s career as an art dealer is 1980, when he opened the Larry Gagosian Gallery in Los Angeles. As early as 1972, though, he had been working to find ways to support creatives and to build a business of his own. Early on he was presenting exhibitions and works by artists who had or would have outstanding careers, including Diane Arbus, Richard Avedon, Chris Burden, Vija Celmins, Judy Chicago, Christo and Jeanne-Claude, Lee Friedlander, Barbara Kruger, Bruce Nauman, Ed Ruscha, and others. He was selling art to some of the most important collectors on the West Coast before he turned thirty.

Larry spent his childhood in downtown Los Angeles and his teenage years in the Valley. His father was a municipal accountant who later trained to be a stockbroker; his mother was an actress. He spent little to no time in museums as a child and had no training in art history. He graduated from UCLA in 1969 with a degree in English literature. After graduation he took various jobs, including working as the assistant manager in a record store, boxing groceries in a supermarket, and taking the midnight shift at a gas station. For over a year he worked in an entry-level role at the William Morris Agency for $90 a week, supervised briefly by Michael Ovitz, though he also worked for Stan Kamen, reading manuscripts and answering phones. Larry recently recalled, “Kamen was an agent with one of the best client lists in Hollywood at the time. He represented Warren Beatty, Elliott Gould, Steve McQueen, and others. It was a lot of fun to work with him because I was able to meet really cool people.”1 He left that job to work as a parking attendant in Westwood, which paid more money.

The part of the story that is less well-known starts in 1972, when he opened the Patio (also called the Open Gallery), an outdoor market in a lovely old Spanish building in the center of Westwood Village, where movie theaters and ice cream parlors brought the neighborhood to life. The building had an L-shaped courtyard running from one street to another, and Larry rented this open-air patio space for $75 a month—which he borrowed from his mother—so that he could offer artisans a place to sell their goods. He even took out a restaurant license so that his sister could sell apricots there. Larry recently mentioned that he showed watercolors by Henry Miller at the Patio: “I found out that Henry Miller lived in Santa Monica Canyon and he was a literary hero of mine. It wasn’t necessarily the most impressive art that I had ever seen, but I was fascinated by writers who made art as well.”2

The Los Angeles Times dedicated an article to the Patio:

Every night this month and on weekends for the rest of the year about 25 craftsmen have been paying Gagosian $6 plus 10% of their gross to shiver and sell to the shopping traffic born of Westwood theaters, restaurants, and college shops. . . . Besides its obvious commercial value, the gallery seems to function on other levels as well. Gagosian believes it has replaced the old Free Press bookstore as the last place in Westwood for hanging out without buying anything. . . . They had Anthony Marks’ paintings on mirror (he did a one man show in London) and Ron Cobb (the cartoonist for the Free Press) has exhibited here.3

Even at this earliest moment we can see traces of Larry’s business acumen and his affinity for the visual arts. And he must have been onto something: he got a write-up in a major newspaper.

At the Patio, Larry noticed vendors selling posters: they were buying the posters for a couple of dollars each, framing them, and selling them for fifteen or twenty dollars each. He could see that they were making good money, so he went into the business and started making a couple of hundred dollars a night, plus bringing in rent from the spaces on the Patio. As Dodie Kazanjian would write in Vogue over fifteen years later, “He was living in the same eighty-dollar a month apartment, a stone’s throw from the beach in Venice. He was reading all the time (‘I was very, very deep into literature and music’), enjoying the beach, ‘hanging out,’ playing tournament chess, and talking about writers until two in the morning in coffee shops. (‘I sound like a beatnik. I wasn’t.’)”4

He had enormous energy and extraordinary ambition. Once he set his mind to something, there was no stopping him.

Constance Lewallen

To better understand the art scene that Gagosian entered in Los Angeles in the 1970s, we might want to go back briefly to the mid-1950s. In 1955, Los Angeles had plenty of homegrown artists, but few galleries and no museum dedicated to contemporary art. The prosperity of the time, combined with the ever expanding entertainment industry in the city, would grow the cultural economy. In 1957, Walter Hopps and the artist Ed Kienholz opened the Ferus gallery; the following year, Irving Blum moved from New York and purchased Kienholz’s share of the business. The Ferus scene nurtured LA-based artists including John Altoon, Larry Bell, Billy Al Bengston, Robert Irwin, Craig Kauffman, Ed Moses, and Ken Price. In 1959, Virginia Dwan—later an early champion of Conceptual art, Minimalism, and Earthworks—opened her first gallery, finding space in Westwood. She would show plenty of work by local artists while also introducing artists from New York and Europe to LA.

In the 1960s the West Coast scene fostered a whole generation of artists, including Chicago, Celmins, Nauman, Ruscha, John Baldessari, David Hockney, and so many more. At the Pasadena Art Museum in 1962, Hopps organized the first-ever group show of Pop art in the United States, New Painting of Common Objects. By the middle of the decade the Los Angeles County Museum of History, Science, and Art had divided into two institutions, one of them the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. In 1965, Artforum magazine moved down from San Francisco into an office above the Ferus Gallery.

Even while the arts community flourished, it was a challenging time in the city. The Vietnam War was tearing the country apart; young men were being drafted against the backdrop of antiwar protests. The Manson-family murders and random acts of violence heightened the looming sense of fear that haunted residents.

During this period, the Watts neighborhood in southern Los Angeles was home to a vibrant Black community and to a number of Black artists working in assemblage who would later prove hugely influential, including Melvin Edwards, David Hammons, John Outterbridge, Noah Purifoy, and Betye Saar. But the devastation caused by the Watts rebellion of 1965—which witnessed brutal violence, widespread looting, arson, over thirty deaths, and more than $40 million in property damage—left a calamitous mark on the community. When asked about the rioting, Larry has said, “In 1965 I was at UCLA, and the Watts riots [made a deep impression] on me. The intensity and scope of it was beyond anything that I had ever seen or experienced. I’ll never forget it.”5

This was also a time of community building in the Latino community. In the East Los Angeles Walkouts (or Chicano Blowouts) of March 1968, 15,000 students protested unequal educational opportunities in high schools, ultimately presenting a list of demands to the city’s Board of Education. The first Chicano art gallery, established in East Los Angeles in 1969, actively promoted the growing movement, celebrating artists whose works responded to social protest and community empowerment.

The LA gallery scene changed in the early 1970s as the country went into an economic recession. Many of the galleries that had helped to develop the city’s reputation as a cultural center closed, or moved to New York or Europe; these included Ferus, Rolf Nelson, Virginia Dwan, Felix Landau, and Eugenia Butler. This shift likely played a role in opening up more opportunities for younger dealers to make their mark. Describing the hard turn taken by the Los Angeles art scene in the early 1970s, the West Coast art critic Peter Plagens wrote, “The West Coast hit the late sixties with some optimism: Los Angeles had established itself as the ‘second city’ of American art and expected to provide for the coming art-and-technology boom. But a funny thing happened on the way to the pantheon: The West Coast art scene hit the skids—not collapsing, but flattening out. The most noticeable leveling took place in Los Angeles, where hopes were raised highest.”6

By December of 1974, Larry had opened a small indoor gallery in the same building complex as the Patio, at 1017 Broxton Avenue. Prints on Broxton was advertised as “selling contemporary prints, custom frames, and original graphics, by a wide range of artists, including Hundertwasser, [Frank] Stella, [Victor] Vasarely, [Joe] Goode, [Paul] Wunderlich, and Chicago.”7 By that point the business focused on making custom frames and selling signed lithographs for several hundred dollars each. Kim Gordon, who would cofound the iconic band Sonic Youth a few years later, was one of the framers. She remembered this period in her memoir Girl in a Band: “Frame after frame—I must have assembled thousands of those things, and the dimensions twenty-four by thirty-six are still carved in my brain.”

Even when he only had one wall to show on, he did it well.

Doug Cramer

In 1975, Larry turned thirty years old. His energy for business was expanding, his taste in art was growing more sophisticated, and he started paying close attention to art magazines. One day he was flipping through Art in America or Artforum and saw photographs by Ralph Gibson. The images made an impression on him and he felt they would make a beautiful exhibition in Westwood Village. Gibson lived in New York so Larry gave him a call, they had a great conversation, and Gibson invited him to make a studio visit. Larry had not been to New York more than once but he made the trip, went to Gibson’s loft on West Broadway, and left with an Agfa box filled with photographs. He brought these back to Los Angeles, had them framed, mounted the exhibition Ralph Gibson: New Directions, and brought Gibson out for the opening. A few of the images were a bit risqué, which shocked the landlord, who almost shut the show down before it opened; but Larry convinced him that the work was in museum collections, which impressed him enough to leave it alone. Robert Mautner at Artweek reviewed the show: “Although a few of the better known images from the books have been included in his show at ‘Prints on Broxton’ in Westwood village, the most exciting aspect of the exhibit is the new work which is being presented for the first time in this area. . . . the exhibit is a must for Los Angeles viewers.”9 That is a remarkable review for the first serious exhibition that Larry put together. And he sold all of the prints.

It turned out that Gibson was repped by Castelli Graphics, the dedicated prints and photography gallery of Leo Castelli. This was fortuitous for Larry because the introduction to Castelli led to a long and prosperous working relationship between the dealers. To broaden the reach of his gallery’s artists beyond New York, Castelli had collaborated with West Coast galleries since the 1960s, most significantly with Blum of Ferus. By the time he met Larry there was a precedent in place for a working relationship that would allow Larry to present Castelli’s artists to Los Angeles audiences, creating new market opportunities for them, although this wouldn’t begin until the 1980s.

In that same year of 1975, Larry hired Constance Lewallen, who had worked for Klaus Kertess at the legendary Bykert Gallery in New York before moving to Los Angeles in 1972. She had taught a few art-history classes at Santa Monica College and was working at Cirrus Editions, which published prints with some of the best artists in Southern California. Larry persuaded her to leave Cirrus and come to work for him, helping to put her on a path to becoming an influential bicoastal curator of contemporary art. At Prints on Broxton, she organized the exhibitions while he took care of the business side: “He didn’t know much,” she would remember, “but he sure learned fast. He had good instincts before he had the knowledge and that intensity was always there. He read and read and read. He had enormous energy and extraordinary ambition. Once he set his mind to something, there was no stopping him.”10 It was a bold move for a young businessman who had run a gallery for less than a year to hire a budding young curator. Lewallen “had good ideas,” Michael Auping writes, “and Gagosian, who was at an early point in his own career, embraced them. He had offered her a big raise (a whopping $25 more a week, which was a lot back then) to leave her previous job and she remembered that time fondly, even sometimes recalling, ‘He let me bring my kids to work when they weren’t in school and I couldn’t get a babysitter.’ In those early years, Connie’s expertise was influential in shaping the gallery’s burgeoning program, which spanned between classic modernism and the new avant-garde.”11 Looking back over Larry’s career, one can see that he has always sought guidance and advice from people he respects, particularly by hiring museum-level curators. This pattern has continued into the present day, with some of the most sophisticated scholars and curators of our time joining his gallery over the years.

In July of 1975, Larry put together a summer group show of drawings, paintings, and assemblage that marked the first time he showed work by Burden, Nauman, and Ruscha, among others. By that point Burden had already developed a reputation for his unnerving performance art. Auping, then a local grad student in art history, remembers,

Along came Chris, who woke us all up from our meditations. You could not ignore his drama and I have no doubt that he was conscious of constituting an assault on Light and Space as a term and a phenomenon. . . . [Robert] Irwin taught on and off at the University of California, Irvine, when Chris was getting his masters there. It’s easy for me to see now that his grueling masters show—which consisted of Five Day Locker Piece (1971), in which he locked himself in one of the school’s small portfolio lockers for five days—was a twisted reaction to Irwin’s and James Turrell’s use of a NASA anechoic chamber to sensitize themselves to space and light.12

Lewallen once recalled the early days of working with Burden: “I remember one day Chris Burden came and wanted to air a TV ‘commercial’ where he’d say, ‘Leonardo Da Vinci, Michelangelo, Rembrandt, Vincent van Gogh, Pablo Picasso, Chris Burden!’ He sat at my little desk at the Gagosian Gallery after it moved to La Cienega Boulevard, and together we called TV stations and bought ad slots. You could get a 2:00 am slot for $50 or something.”13

In August of 1975, Prints on Broxton became Broxton Gallery, marking both the success of Larry’s first year in the space and a notable shift in his approach to the business. Larry says, “I had started showing and selling more high-end works of art. The business was shifting away from prints and editions, and though there were plenty of shows of photography, they were more serious exhibitions.”14 Broxton Gallery’s first show was Duane Michals: Photographs. Michals had enjoyed a solo exhibition at New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) just a few years earlier.

A few months later Larry brought together the complete lithographic works of Vija Celmins, an exhibition that many years later he would remember as pivotal: “My first show that wasn’t photographic was Vija Celmins. I really loved Vija Celmins’s work, and I was able to assemble her entire oeuvre of graphic work.”15 Lewallen recalled meeting Larry for the first time when she was working at Cirrus Editions:

[Cirrus] was printing artists like Ed Ruscha and Vija Celmins at the time as well as lots of younger LA artists. . . . that’s when I met Larry Gagosian, who nobody knew then. He had a poster gallery in Westwood and wanted to buy Vija Celmins’s long ocean lithograph from Cirrus. It’s a beautiful print. The edition had sold out but he would call all the time wanting to buy it, and I’d say, “You know, I have to tell you, we just don’t have any available.” He was relentless. And finally I told Jean Milant, who was the Cirrus’s founder and director, “This guy is driving me crazy. Can’t you find a proof or something?” And he did. He actually found an artist’s proof. So one day Larry called and I said, “You’re not going to believe this, but we actually do have a print to sell you.” So then he had the gall to say, “Will you deliver it to me?” . . . It turns out that I was living close to his shop, so I agreed. And the funny part is that [after he hired me] there was one month he couldn’t pay me, and he gave me that print.16

He started collecting more seriously, acquiring Joseph Beuys’s Felt Suit (1970), for instance, and he was careful to deal with artists whose work captured his attention, excited him, and pushed at the edges: “Something that I’ve always paid attention to is to work with the most important artist that I could.”17 He didn’t shy away from challenges and his enthusiasm for ambitious artists such as Burden began to push them to think bigger. He also found ways to cultivate the collections of clients. As early as 1976, he started selling to David Geffen, whom he met through Kamen, one of his former bosses at William Morris. He also grabbed the attention of Barry Lowen, a television executive who spotted the Beuys suit in the window of his gallery. Lowen in turn made the introduction to Doug Cramer. And Steve Martin was active on the scene as well, often stopping by the gallery to see the shows, discuss the art, and get to know Larry.

Larry was leaning into his presence on the West Coast as a way to attract East Coast artists with solid reputations and followings, expanding their audience reach and connecting them with a serious new client base.

Alison McDonald

The gallery was getting traction in the media, with reviews coming in for most of Larry’s exhibitions. When he opened a Friedlander show in 1976, an Artweek reviewer observed, “The Friedlander exhibit at Broxton Gallery provides a rare opportunity for west coast viewers to experience the rare depth and insight of this well-known east coast artist.”18 At this point Friedlander had an established reputation in New York; along with Arbus and Garry Winogrand, he had been the subject of John Szarkowski’s groundbreaking New Documents exhibition at MoMA in 1967, endorsed as one of a new generation of photographers focused less on documenting “truths” than on examining their own perceptions of and interactions with the world. With shows like this one, Larry was leaning into his presence on the West Coast as a way to attract East Coast artists with solid reputations and followings, expanding their audience reach and connecting them with a serious new client base.

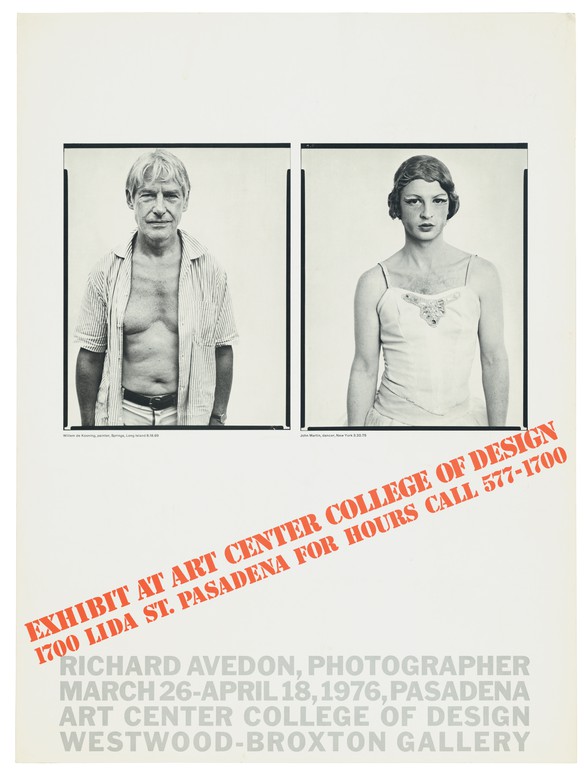

Larry first encountered Avedon’s murals in New York’s Marlborough Gallery in 1975, in the photographer’s first major show at a commercial gallery. Each of the four murals on view depicted a row of larger-than-life figures lined up side-by-side, towering over the observer. One of them showed eleven members of the Mission Council, a group of generals, diplomats, and other officials responsible for running the Vietnam War. This work was shown alongside a mural of the Chicago Seven, a group of men who had protested that war and had been arrested and charged with conspiracy to incite riot. The show captured the tension of the era and participated in the evolution of photography as an accepted medium of fine art. Larry wanted to bring it to Los Angeles, as he had successfully done with other exhibitions:

Stunned by their scale and audacity, I made immediate inquiries about bringing the exhibition to the West Coast, where I was based at the time. My first gallery in Los Angeles was diminutive, far too small to accommodate these photographs of unprecedented scale, but I managed to negotiate for the exhibition to travel to the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena, where it opened in the spring of 1976, before continuing on to Seattle, Tokyo, and Montreal. At the same time, I presented an exhibition of smaller, related works in my gallery, some of which remain cornerstones of my personal collection to this day.19

The attention won by these and the Marlborough shows helped to propel the institutional recognition of an overtly political body of work. They came at a critical moment in Avedon’s career, solidifying his reputation beyond the fashion photography that had catapulted him to early success. Larry was well positioned in the south-California art scene and saw a role he could play for the artist at that moment: he was attuned to the acclaim and audience reach that Avedon had achieved in other aspects of his career, he understood the region’s institutional dynamics, he embraced Avedon’s powerful imagery, and he recognized the potential for all involved. In March of 1976, around the time of the Pasadena exhibition, he ran an ad in the Los Angeles Times: “Broxton Gallery is the exclusive southern California representative of Richard Avedon.”20

Larry’s interest in photography persisted throughout the 1970s. In May of 1976 he hosted Broxton Sequences: Sequential Imagery in Photography, which presented eighteen photographers, including celebrated figures such as Michals, Lynda Benglis, Bernd and Hilla Becher, Walker Evans, and more. That July he showed works by Bill Brandt, Jo Ann Callis, and Abigail Perlmutter; and in 1977 he exhibited color photographs by William Christenberry, William Eggleston, John Gossage, Joel Meyerowitz, Nicholas Nixon, and Stephen Shore. Between 1975 and 1977 he hosted fifteen photography exhibitions, including solo presentations by Bevan Davies, Larry Fink, Steve Kahn, André Kertész, and, twice, Elyn Zimmerman.

One day Chris Burden came and wanted to air a TV commercial. . . . He sat at my little desk at Gagosian and together we called TV stations and bought ad slots.

Constance Lewallen

In 1976 Larry opened Robert Wilhite: Telephone performance OR Attendance by telephone only, a performance-based work that could only be viewed in the form of verbal descriptions spoken by the artist to callers on the telephone—the space’s windows were blocked out, no two callers got the same description, and half the callers received a sound work created for the event. Wilhite had attended UCLA and had been a student of Bell, Irwin, and Moses; in 1977, when Burden curated a show of performance art at the Los Angeles Institute of Contemporary Art titled Live from L.A., he invited Wilhite to participate. Even this early in Larry’s career, we witness his embrace of performance and conceptual works, which are often set outside commercial parameters and produce no physical objects that can be sold. His desire to support artists working in this way clearly laid the groundwork for future interactions with artists such as Walter De Maria, whom Larry would champion in the future.

Brice Marden was represented in a group show at the gallery, alongside Ruscha and other artists, as early as 1976. Curated by Lewallen and titled Works on Paper: East and West Coast Artists, the show brought together an impressive selection of artists working across styles, ranging from expressionist abstraction to sharp-focused realism. A review describes it as presenting “a pluralist panorama of what drawing is and dares to be these days.”21 Larry had shown work by Ruscha in a group show as early as 1975, then again in Lewallen’s exhibition in 1976.

Originally from Oklahoma, by the 1970s Ruscha was a fixture in the Los Angeles art community. He had met Castelli in 1961, had had his first solo show at Ferus in 1963, had enjoyed success at a young age, and his reputation was still on the rise. While riffing on Pop art and other art-historical references, his work was entirely unique. Blum recalls, “Ed Ruscha came to my attention in 1963. He was doing fascinating work. Those are the years of the big Twentieth Century Fox logo, the mural-size Standard-station paintings, the large painting of the L.A. County Museum on fire.”22 In the 1970s, Ruscha was exhibiting with Castelli in New York and at Ace Gallery in Los Angeles, but he started working with Larry in small ways, such as group exhibitions. The seeds of that relationship would grow into a dynamic partnership that would continue for the next five decades.

By August of 1976, the Broxton Gallery had moved into a space at 669 North La Cienega Boulevard that had previously been occupied by the well-known Mizuno Gallery. In September of that year it hosted Chris Burden: Relics, a pivotal exhibition showcasing artifacts from the artist’s early performances. Around this time, Larry acquired the padlock to the locker in which Burden had confined himself during Five Day Locker Piece, arguably his first mature work, for a price of $500. A review of the show by William Wilson in the Los Angeles Times read, “Chris Burden, widely noted for perpetrating scary acts some allege to be artworks, shows relics of his escapades. We see pushpins he instructed a volunteer to insert in his body, a knife with which he threatened to slit the throat of a collaborator, live electric wires he jabbed into his chest before a group of onlookers. . . . There are any number of ways to interpret Burden’s acts, few of which have to do with aesthetics.”23 Burden responded to the review later that month: “I found William Wilson’s review of my show at the Broxton Gallery to be misinformed, extraneous, and irresponsible. My work almost invariably suffers at the hands of the popular media, which have preconceived notions about what art can or cannot be.”24

I moved fast because I didn’t perceive what the boundaries were. There’s a benefit in not having any kind of preconceptions about structure or hierarchy.

Larry Gagosian

The exhibition that followed Relics, in October of that year, was Christo: Drawings, Collages, Photo-documentation, which celebrated Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s Running Fence project and was presented simultaneously with an exhibition on the work at the Pasadena City College Art Gallery. Running Fence was an enormously ambitious undertaking, developed after the artists’ influential 1971 orange Valley Curtain near Rifle, Colorado. Installation of the fence had been a massive endeavor, completed on September 10 of 1976; the work consisted of 200,000 square meters of heavy white nylon fabric hung from steel cables, eighteen feet high and over twenty-five miles long, stretching from Petaluma, California, to the Pacific Ocean. The project was the culmination of 3 ½ years of planning, negotiation, and collaboration, and was financed entirely by the artists through sales of preparatory drawings, collages, scale models, and lithographs—the kinds of materials in Larry’s exhibition. In response to the Broxton show, Henry J. Seldis wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “For those who missed Christo [and Jeanne-Claude]’s actual Running Fence up in Sonoma and Marin Counties, some excellent renderings of [their] concepts are also being shown. They reveal Christo [and Jeanne-Claude] to be first-rate drafts[people] as well as environmental conceptualists.”25

The following month, the Broxton Gallery presented twenty color photographs by David Hockney and photographic portraits of artists by Hans Namuth. The Los Angeles Times again reviewed the show: “Back-to-back solo shows of photographs by a painter and photographs of painters. The latter are by Hans Namuth who seems to play it fairly straight with his subjects. . . . The painter showing photographs is David Hockney, heir-apparent to the unofficial title of Britain’s best pictorial artist. Hockney’s photos are entirely in his familiar style. . . . his photographs are richly, almost uncomfortably, sensuous in, for example, images of a young male nude. This quality is suppressed in Hockney’s paintings and drawings objectified in urbane detachment.”26

When asked about other dealers he was paying attention to during these years, Larry said, “Nick Wilder had a gallery at the time and I visited frequently. He was showing Hockney and others. I remember a show of Cy Twombly blackboard paintings that knocked me out. Nick and I became fast friends and he let me spend time in his back room, looking for works that I could sell. He was an established dealer and a very good ally.”

Exhibitions at the Broxton Gallery continued until April of 1977, after which Larry started working from his house in Westwood. (He lived in a historic modernist complex, designed in 1937 by the renowned architect Richard Neutra.) Cramer recalls,

Barry [Lowen] told me there was a former William Morris agent who was in the business of buying and selling contemporary art, operating out of a little apartment in Westwood. Barry thought he had a great eye and wonderful contacts with this young new group, and he said he was someone I should know and work with. He took me to see him in a little one-room apartment with a sort of loft in it. It was neat and clean—as all of his offices and galleries since have been. Even when he only had one wall to show on, he did it well.28

Larry expanded his own collection as well: “I’d started buying some small works and drawings. I’d bought a Brice Marden piece. I’d bought a Sol LeWitt drawing. I was still kind of drawn to minimal art. It was more accessible at the time—by which I mean less expensive.”29 By 1978 he was traveling more and gaining visibility in New York. He was on the verge of the next step in his career: “I was a hard worker in California, but you can only do so much there. That’s one of the reasons I wanted to leave. I could always make a nice living and go to the beach every day and bodysurf and hang out, or I could come to New York and kind of ruin my life. I decided to come to New York.”30

1Larry Gagosian, in conversation with Alison McDonald, November 20, 2023.

2Ibid.

3Beth Ann Krier, “A Gallery of Folkloric Oddities,” Los Angeles Times, December 17, 1972.

4Dodie Kazanjian, “Going Places,” Vogue, November 1989, p. 415.

5Gagosian, in “In Conversation: Mike Milken and Larry Gagosian,” Gagosian Quarterly, July 7, 2020. Available online at https://gagosian.com/quarterly/2020/07/07/mike-milken-larry-gagosian-in-conversation/ (accessed November 15, 2023.)

6Peter Plagens, Sunshine Muse: Art on the West Coast, 1945–1970 (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1999), p. 155.

7Prints on Broxton, advertisement in Los Angeles Times, December 15, 1974.

8Kim Gordon, Girl in a Band: A Memoir (New York: HarperCollins, 2015), p. 65.

9Robert Mautner, “Ralph Gibson: New Directions,” Artweek 6, no. 23 (June 14, 1975): p. 13.

10Constance Lewallen, quoted in Suzanne Muchnic, “Art Smart,” Los Angeles Times, October 15, 1995.

11Michael Auping, “Game Changer: Constance Lewallen,” Gagosian Quarterly, Fall 2022, p. 186.

12Auping, in Alison McDonald, “At the Edge. Chris Burden: Prelude to a Performance,” Gagosian Quarterly, Summer 2022, pp. 85–86.

13Lewallen, in Dena Beard and Lewallen, “Making It Live: Dena Beard and Constance M. Lewallen in Conversation,” The View from Here no. 4 (October 11, 2016). Available online at https://openspace.sfmoma.org/2016/10/making-it-live-dena-beard-and-connie-lewallen-in-conversation (accessed November 15, 2023).

14Gagosian, in conversation with McDonald.

15Gagosian, in Peter M. Brant, “Larry Gagosian,” Interview, November 27, 2012. Available online at www.interviewmagazine.com/art/larry-gagosian (accessed December 2, 2023).

16Lewallen, in Beard and Lewallen, “Making It Live.”

17Gagosian, in Negar Azimi, “Larry Gagosian,” Bidoun 28 (Spring 2013). Available online at https://archive.bidoun.org/magazine/28-interviews/larry-gagosian-with-negar-azimi/ (accessed December 2, 2023).

18Robert Mautner, “Insight into Friedlander,” ArtWeek 7, no. 2 (January 18, 1976): p. 13.

19Gagosian, Foreword, in Mary Panzer, Louis Menand, Bob Rubin, et al., Avedon: Murals and Portraits, exh. cat. (New York: Gagosian Gallery, 2012), p. 7.

20Gagosian advertisement, Los Angeles Times, March 21, 1976.

21Sandy Ballatore, “Directions in Drawing,” Artweek 7, no. 15 (April 10, 1976), p. 5.

22Irving Blum, in Roberta Bernstein, “An Interview with Irving Blum,” in Ferus, exh. cat. (New York: Gagosian Gallery, 2002), p. 33.

23William Wilson, “Art Walk: A Critical Guide to Galleries,” Los Angeles Times, October 1, 1976.

24Chris Burden, “An Artist Replies,” Los Angeles Times, October 17, 1976.

25Henry J. Seldis, “La Cienega Area,” Los Angeles Times, October 22, 1976.

26William Wilson, “Art Walk: A Critical Guide to the Galleries,” Los Angeles Times, November 26, 1976.

27Gagosian, in conversation with McDonald.

28Doug Cramer, quoted in Charles Kaiser, “The Art of the Dealer,” Interview Magazine, July 1989, p. 56.

29Gagosian, in Brant, “Larry Gagosian.”

30Gagosian, quoted in Kazanjian, “Going Places,” p. 462.