Adam Szymczyk is a curator and author based in Zurich. He studied art history at the University of Warsaw and was a cofounder of the Foksal Gallery Foundation, where he worked as a curator from 1997 to 2003. He was director and chief curator of Kunsthalle Basel between 2003 and 2014, and then served as artistic director of Documenta 14 in Athens and Kassel between 2014 and 2017. At present, he is curator-at-large at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. In 2022, he founded the Verein by Association, a nonprofit association for contemporary arts and culture in Zurich. Photo: © Melanie Hofmann, Zurich

I have been asked on many occasions what we actually taught the students in the Environmental Art department at Glasgow School of Art. . . . Douglas Gordon’s comment that he was taught, ‘To sing. Not how to sing, but simply TO sing’ described a prevailing attitude in the department.

—David Harding, “On Singing”

My first encounter with the work of Douglas Gordon was in 1995, one year before he received the Turner Prize. While in Amsterdam at de Appel’s curatorial training program—initiated by the art center’s director at the time, Saskia Bos—I visited the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven together with fellow students Annie Fletcher, Nina Folkersma, Clive Kellner, and Kay Pallister to study the collection and learn something about exhibition-making from the then-director of the museum, Jan Debbaut, and his colleagues. “When on a research trip as a curator in a foreign city, don’t waste your time: always take a cab from the airport,” advised chief curator Frank Lubbers wisely. We were penniless, but, luckily, Douglas Gordon’s show was on view. It was the most comprehensive museum exhibition of his work to date, and we weren’t prepared for the experience.

As the third installment of the museum’s exhibition series Entr’acte, the show brought the title’s express intent to its limits. It was an overwhelmingly impressive understatement—like a casual exercise in tightrope walking—with great suspense in endless stasis. Large and medium-sized rear projections of Gordon’s now-iconic video works seemed to hover supernaturally in the dark cavernous space of the Van Abbemuseum’s factory-like galleries. Upon leaving the museum, I found a 35mm slide in a white plastic frame in a pocket of my jacket, which I thought had made it there by miracle, yet it was, as I understood only much later, Gordon’s unsolicited souvenir for visitors (would a gift made this way be the opposite or an analogue of theft?)—a black-and-white photograph of a man with eyes closed, a half-crazy smile, and outstretched hands. What I assumed to show a lone play of blindman’s buff turned out to be the portrait of a mind reader (Pocket Telepathy, 1995). He has been trying to read my thoughts ever since.

In Bangladesh, blindman’s buff is called “blind fly.” In the exhibition, a large projection showed a close-up of a fly lying on its back, dying, in a loop. The piece, Film Noir (Fly) (1995), was disturbing, repulsive, embarrassing, fascinating. So were the other dark videos, including Trigger Finger (1994), a close-up of a hand whose finger compulsively pulls a trigger that is no more, and 10ms-1 (1994), a looped fragment of archival footage recording a World War I soldier, shell-shocked, attempting to stand up. The title refers to gravitational acceleration, or the pull of the Earth—as did Bas Jan Ader when he said, “Gravity made itself master over me.” The soldier seemed to be receiving stage directions off-screen, but the video itself was silent, and there was Silence in the Museum, as announced by Gordon in a text piece in 1992.

In 1998, a major monograph on Gordon’s videos and works with text, aptly titled Kidnapping, was published by the Van Abbemuseum. Among the works discussed in the book (and included in the Eindhoven show) was the piece List of Names, begun in 1990 and ongoing, listing all the individuals Gordon remembered ever having met. I still recall the frisson of looking for my name on the list, but I cannot remember whether I found it. Now, I am not searching for it anymore.

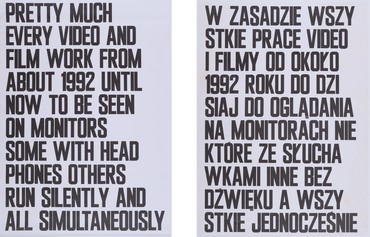

In 1999, Joanna Mytkowska, Andrzej Przywara, and I invited Gordon to do a show at Galeria Foksal in Warsaw, a notoriously tiny nonprofit space we ran together, with full dedication and aware of its history (it was founded by a group of artists, including Tadeusz Kantor and Edward Krasiński, and art critics in 1966), boasting a stellar cast of Polish and international conceptual and post-conceptual artists who mostly produced their works on-site. We thought Gordon would show one of his videos or make a new one—he chose to show all of them, including the ones I had seen at the Van Abbemuseum. The work’s lengthy title, Pretty much every film and video work from about 1992 until now. To be seen on monitors, some with headphones, others run silently and all simultaneously, nearly filled the classic Foksal poster, printed analog in stylish black block letters. Gordon simply gave everything he had to the show, and I have been convinced ever since that he is one of the most generous artists I know. We organized some thirty commercial TV monitors of any make and size we could find, in addition to a similarly heterogenous armada of crappy VHS players. We connected them to the TVs, plugged the power cables into multiple socket strips, and played it all. The effect was eerie. Here, an unshaved hand wrestling or caressing a shaved hand (and the other way around; A Divided Self I and II, 1996); there, a finger tattooed completely black, looking limp, sinister (Three Inches (Black), 1997—“the measurement of three inches corresponds to the idea that this is the distance that could make a fatal wound in the body; the distance necessary to penetrate a vital organ, the heart in particular,” in Gordon’s words); elsewhere, a bare-chested Morrissey in concert with the Smiths, looking mad and holy, an ascension in slow motion (Bootleg (Bigmouth), 1996). All those minor stage acts were so disparate that they made perfect sense together. Far Too Many Things to Fit into so Small a Box, as Lawrence Weiner (who also had a show at Foksal, in 1990) soberly observed elsewhere, in 1996. Context is half the work. Which half?

Our small space would heat up quickly and rather dramatically with the cathode ray tube TVs and VHS players all turned on at once. It gave the show the feeling of a basement club, a tiny, dimly lit den, or a nighttime binge-watching movie session at home. I was not able to experience this first impression again in any of the later exhibitions of the work that I visited, as it evolved similarly to the List of Names, with new films and videos becoming part of the piece. I was proud to see it in Mixing Memory and Desire, a show curated by Ulrich Loock at the Kunstmuseum Luzern, in 2000, but could hardly bear the fact that the intimacy and modesty of the setting in Warsaw had been translated into a public “archival sculpture” within a large group show at a museum. The piece was growing and growing. I saw it again in 2006, at the Royal Scottish Academy Building in Edinburgh, as part of Gordon’s homecoming retrospective spanning several locations, with beautifully installed text works at Inverleith House.

Recently, I stared at it at the Fondation Beyeler in Riehen in a curious one-day exhibition preceding a fundraiser on September 4, 2022, where I met Douglas in his trademark Scottish/Adidas attire, together with my co-student and friend from Amsterdam days, Kay (no Scottish attire), who has been working with Douglas since time immemorial. By then, the piece counted over ninety individual works—roughly three times more than in 1992—and it was described by the museum as an “encyclopedically aimed, compressed retrospective.” Raised on VHS, I can barely look at flat-screens (joking). At the Beyeler, I remember a bloodshot eye gazing at me from a large telephone screen used in the installation, and images of a burning grand piano in the beautiful and heart-wrenching work The End of Civilisation (2012), which Gordon filmed in Cumbria (where the Roman world once ended). I also glimpsed I had nowhere to go: Portrait of a displaced person (2016), which we showed during documenta 14 in Athens and Kassel in 2017—a mostly imageless, feature-length film of Jonas Mekas doing a voice-over reading of his eponymous diary, and appearing once to play a tune on the accordion. Other than that, I Remember Nothing. It was the last time I saw Pretty much every film and video work from about 1992 until now. Will I see it again?

The epigraph is from David Harding, “On Singing” (blog post), DavidHarding.net, June 26, 2022. Available online at https://www.davidharding.net/?p=438 (accessed January 18, 2024).

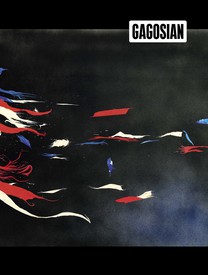

Douglas Gordon: All I need is a little bit of everything, Gagosian, Grosvenor Hill, London, February 1–March 15, 2024

Artwork © Studio lost but found/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, Germany, 2024