Alix Browne is a lifelong editor who has written about art, fashion, design, and culture for W Magazine, T: The New York Times Style Magazine, and others. She has a horse, of course.

Apelles of Kos, artist at the court of Alexander the Great, was a legendary perfectionist. So true to life was his work that when shown one of his horse paintings, real horses whinnied in recognition. (In an alternate telling, a stallion views the painting and attempts to mount it.) But one day Apelles painted himself into a corner. While trying to finish another equine masterpiece, he struggled to get the frothy spittle around the horse’s mouth to his exacting standards. In a fit of frustration, he picked up the cloth or sponge he had been using to clean his brushes and hurled it at the offending spot. And, well, this being the stuff of legend, you can probably guess the result: Nailed it!

It’s not a stretch to read this story of the artist hellbent on perfection as an allegory for the mindset of the artist more generally. The Pyrrhonist philosopher Sextus Empiricus would refer to Apelles in his discussion of ataraxia, a serene calmness untroubled by mental or emotional disquiet—something Apelles achieved only after literally throwing in the towel. Ataraxia was considered the ideal state for soldiers going into battle, but also, it would seem, for the artist staring into the abyss of a blank canvas. Fun fact: this story provided the title for artist Carol Bove’s 2011 installation The Foamy Saliva of a Horse.

Anyone looking for an actual horse in that Bove work may be disappointed. But that Apelles was attempting to paint a horse, rather than, say, a bird, or an ass, or a person, does not seem incidental. The relationship between artists and horses—between Homo sapiens and Equus ferus caballus, if you want to get right down to it—is long, complex, rich, storied, and copiously illustrated. The horse ranks among the most popular subjects in the history of art, second perhaps only to humans themselves. When that first anonymous artist walked into a cave in France more than 30,000 years ago, what did he choose to paint? A horse, of course.

Many artists have made horses their life’s work, including the eighteenth-century British painter George Stubbs—who arguably one-upped Apelles in the maniacal pursuit of realism, dissecting nearly a dozen horses in order to better understand their anatomy—and more recently the American artist Susan Rothenberg, who held the horse up like a mirror. “The horse was a way of not doing people, yet it was a symbol of people, a self-portrait, really,” she said. Rubens was a prolific painter of horses as well as an avid equestrian. Reviewing an exhibition of equine-themed works by Giorgio de Chirico, the writer Jennifer Krasinski speculated that as an artist devoted to the classics, de Chirico might have painted horses because, well, historically painters painted horses. But the truth is that pretty much every major artist living today has at one point or another had a horse walk into their purview. Name an artist and I will—with some luck—rustle up a horse.

Matthew Barney: Cremaster 3 (2002). Saratoga race track. A heat of zombie horses, all running dead, their flesh falling off of their bodies. Hard to forget that one.

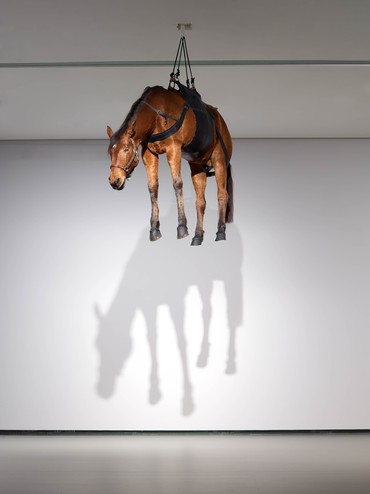

Maurizio Cattelan: The Ballad of Trotsky (1996). A taxidermied horse hangs limp from the ceiling—“a monument to the paralysis of a universal utopia and the usurpation of romantic idealism by the darker side of human nature,” according to his gallery.

Yayoi Kusama: Horseplay (1967). As part of this happening in Woodstock, New York, Kusama covered herself—and a horse—in polka dots.

Kara Walker: The Jubilant Martyrs of Obsolescence and Ruin (2015). Walker’s three equestrian figures refer to the Confederate Memorial Carving at Stone Mountain, Georgia. Bound at the hoof, Jefferson Davis’s horse, Blackjack, is being carried on the back of a female slave.

Christopher Wool: Untitled (1988). TROJNHORS. His first stenciled word painting.

Nick Cave: Heard (2012). This enchanting soundsuit performance piece brings a herd of horses to life.

Mamma Andersson: The Horse, the Ghost, the Sun (2020). As a child, she yearned to have her own horse.

Richard Prince: Untitled (Cowboy) (1989). That’s an easy one.

Marlene Dumas: The Horse (2015–16). A small, unexpected jewel.

Jeff Koons: Split-Rocker (2000). Half of a horse, anyway.

The truly horse crazy (and here I include myself) might delight in the discovery of a lesser-known audio gem recorded by Luc Tuymans and Miroslaw Balka in the lobby of the Porto Palácio Hotel, Porto, Portugal, in 1998 (and released as a limited-edition vinyl LP in 2008), in which the artists deliver their best horse impressions. Clip clop, clip clop. Neeeeiiiigggghhhh. The title of that one is, appropriately, Crazy Horses.

In painting, sculpture, photography, film, performance, and sound, we encounter the horse as a symbol of status, power, escape, beauty, fragility, suffering, vulnerability, virility. There are epic monuments and naive girlhood fantasies. Historical figures and unicorns. Studs and nags. And in these wide-ranging depictions of the horse, we also encounter ourselves, at our best and, occasionally, at our worst.

But are the artists behind all of these works taking on the horse simply because they had no choice? In a way, you could argue, yes. Most of the artists I have spoken to a) have zero interest in horses in real life, or b) are actually afraid of them. The echo of hoofbeats through thousands of years of the history of art and horse-powered civilization aside, the horse nevertheless looms large in the contemporary imagination even as horses themselves have disappeared from everyday life. As Ulrich Raulff writes in his epic Farewell to the Horse: A Cultural History, “The more horses forfeit their worldly presence, the more they haunt the minds of a humanity that has turned away from them.” Every single great idea that fueled the nineteenth century, he argues—including freedom, human greatness, compassion, but also subcurrents of history such as the libido, the unconscious, and the uncanny—can be traced one way or another back to the horse. For centuries, the horse has shouldered not only the weight of our physical demands but also all of our metaphorical baggage. Indeed, the horse is unique insofar it is at once phoros (a carrier of something) and semiophoros (a carrier of signs). “We cannot go wrong,” Raulff writes, “if we describe the horse as the metaphorical animal par excellence.”

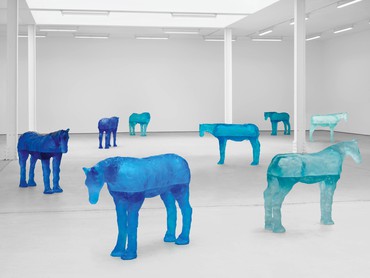

Ugo Rondinone has returned to the horse at different moments in his life as an artist. The first time was in the form of a rainbow poem sculpture spelling out the title of his exhibition a horse with no name (2002). Rondinone had recently moved to New York from Berlin, and the words, he says, addressed very well his new life in America—all broken dreams and unfulfilled expectations and a life left behind.

A year later, in 2003, while on a winter residency in Vienna, Rondinone became mesmerized by a horse he saw walking on a frozen lake, and ultimately took more than 500 photos of it from every possible angle and perspective. He must have seen something of himself in this animal. It became his second a horse with no name.

Years later, in a sort of meditation on the primal, Rondinone created an entire herd of 44 palm-sized horses, forming a single animal out of clay each day over the course of more than a month. In a subsequent series, fifteen of those earthbound lumpen horses were reincarnated as vessels of water and air, cast in blue glass, and bisected to form a perfect horizon between the sea and the sky.

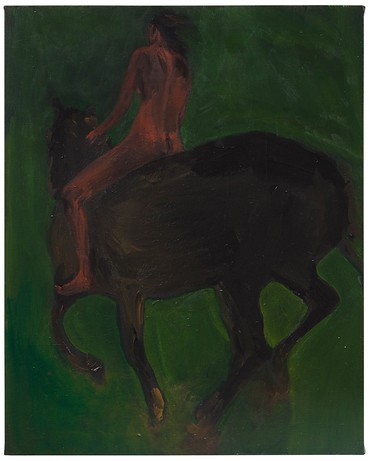

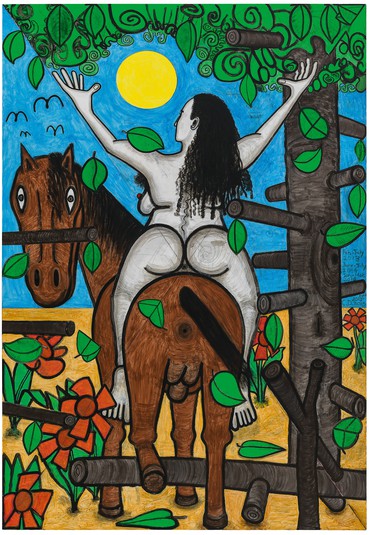

Danielle Mckinney also taps into the universal and the deeply personal in her intimate painting Haste (2021). “I want to capture the movement and the spur-of-the-moment energy of making a fast decision,” says Mckinney of her image of a woman riding bare and bareback into a night landscape. There is a dreamlike yearning to the painting. “Haste is also a tribute to my desire to ride a horse naked in a field,” says Mckinney, who admits to a deep fear of and a deep attraction to horses. “I don’t feel like I can do that in real life, but I can do it in a painting.”

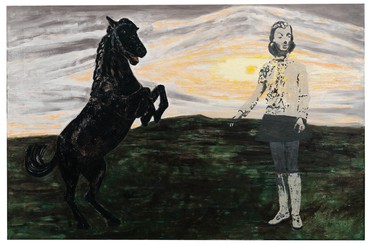

Carroll Dunham was staring down a blank canvas, trying to solve a formal problem, when the horse that would become the star of his painting Horse and Rider (My X) (2013–15) came to him. “This is quite a large painting for me, and the canvas leaned against the wall of two different studios for a couple of years before I really had a sense of what it should be,” he recalls. “I was involved with a large group of paintings organized around the idea of naked human females in nature. I had to struggle for a time before I realized that a figure couldn’t fill the vertical axis of the plane, and in that moment my mind’s eye saw her on a horse.”

A retired draft horse lives down the street from Dunham’s house and studio in rural Connecticut, and he dutifully went to study it, thinking he had some obligation to be realistic. “But soon I realized this was counterproductive and I had to build the horse myself as I made the painting.” Once he fully accepted the subject, he says, the painting almost painted itself.

I would not put money on horses whinnying in recognition of Dunham’s cartoonish equine subject. But there is something knowing—and human—in his expression, the way he turns his head to meet us squarely in the eye. What is he trying to tell us? “I think the horse is looking back out of the painting as a witness, a link between the world of the painting and our world,” Dunham says. “Just as the female human is only concerned with her world, that of the painting. I have no idea what this means.”