AWARE: Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, cofounded in 2014 by Camille Morineau, is a French nonprofit dedicated to the production and dissemination of information about women artists from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Operating through partnerships with museums, universities, and research centers, AWARE has an international outlook and organizes events—symposia, academic study days, prizes, fellowships, guided visits—aimed at making these artists visible. Photo, left to right: Eléonore Besse, Camille Morineau, and Matylda Taszycka © Margot Montigny

Zélie Chabert is a research programs assistant at AWARE. A masters student in the geopolitics of art and culture at the Université Sorbonne Nouvelle, Paris, she studies the management of cultural projects and institutions. She supported Camille Morineau and AWARE staff Eléonore Besse and Matylda Taszycka, the curators of the Modern Women section within Frieze Masters, London.

The latest Art Basel report revealed, once again, that the representation of female artists in the art market “remains persistently lower than their male counterparts.”1 This echoes the 2022 Burns Halperin report, which showed that between 2008 and 2020, art by women artists made up just 11 percent of American museum acquisitions.2 Though 2022 saw historic strides for women artists, notably in Cecilia Alemani’s exhibition The Milk of Dreams at the Venice Biennale, women artists still largely make up the invisible part of the iceberg. This lack of visibility is a complex issue, reaching far back into the past, with the erasure of women artists from art history, and into the present day, where women are in the majority in art schools but systematically find fewer opportunities, less institutional recognition, and less remuneration than their male counterparts. As bell hooks, Adrian Piper, Harmony Hammond, Renate Lorenz, and many others have shown, in the past and now, women artists of color and artist members of the LGBTQI+ community are faced with even greater obstacles.3 Art by Black American women artists, for example, made up 0.5 percent of American museum acquisitions in 2008–20 and just 0.1 percent of worldwide auction sales in 2008–22.4

AWARE: Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions is a nonprofit founded in 2014 to be a force for change. Devoted to increasing public awareness of woman-identifying artists of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, AWARE is based in Paris but works internationally. Its free, bilingual (French/English) website now features over a thousand biographies of women artists from across the globe, art-market “stars” catalogued and cross-referenced side by side with lesser-known artists, all placed within their historical context. This reveals the specificity of each artist’s practice, dismantling the myth of the existence of “feminine art” or “women’s art.” Rather than attempting to expand the canon, nonhierarchical cataloguing and a global outlook allow AWARE to chip away at art-historical norms. The organization’s other initiatives range from podcasts and cartoons to partnerships with international museums, such as the Centre Pompidou and the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, and the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. Simultaneously building on past research while opening new avenues for scholarship, AWARE is a tool for curators and researchers, collectors and gallerists, as well as for the wider public.

When AWARE organized the Spotlight section of London’s Frieze Masters show in 2022, its curatorial thinking was consistent with its nonhierarchical approach: lesser-known series by recognized artists such as Leonor Fini were presented in dialogue with work by Sister Gertrude Morgan and Vivian Springford. AWARE’s 2023 Modern Women exhibition, an entirely new section of Frieze Masters, goes a step further, demonstrating Griselda Pollock’s refutation of the idea that “there were no women modernists” and reconsidering what we mean by modern art.5 The section spans 1880 to 1980, a century that begins with the first wave of feminism in Europe and the United States and covers the 1970s, integrating second-wave feminism and the beginnings of feminist art. Modern Women takes its name from a groundbreaking book published in 2010 by New York’s Museum of Modern Art, and has its base in Lucy R. Lippard’s idea that “feminism’s greatest contribution to the future of art has probably been precisely its lack of contribution to modernism.”6 It breaks with the idea of modernism as a single, linear, and progressive narrative by revealing, on the contrary, the diversity of “modern” practices in echo of diverse political contexts and struggles, as well as searches for singular forms of expression. Modern Women builds on landmark feminist exhibitions such as L’altra metà dell’avanguardia 1910–1940, at the Palazzo Reale, Milan, in 1980; elles@centrepompidou, at the Centre Pompidou, Paris, 2009–11; and We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965–85, at the Brooklyn Museum in 2017. Our aim is to present modernities from the perspective of l’altra metà, reframing the modern by addressing a century of creation through multiple points of view, and encompassing a broad range of mediums: painting, sculpture, textile, computer art, and photography. The works range from the nonpolitical to the overtly activist. The section progresses by interweaving different narratives, dialogues, and echoes, from figurative to abstract to feminist. It demonstrates simultaneous modern perspectives, highlighting the singularity of each artist’s production while encouraging deeper readings.

The four artists and works on the following pages are among those included in Modern Women. In the spirit of AWARE’s website, each artist’s “portrait” has been written by a different art historian from the nonprofit’s team.

— Eléonore Besse, Camille Morineau, Matylda Taszycka

Ethel Walker

Decoration: Evening (1936)

“I am going to be painted, stark naked, by a woman called Ethel Walker who says I am the image of Lilith,” wrote Virginia Woolf in her diary in the early 1930s.7 Walker would already have been in her seventies at the time, but got on well with the Bloomsbury group (whose members she invited to parties, according to Woolf’s diaries), sharing their nonconformist attitude; the lesbian Walker dressed in masculine “severe tailored costumes with shirt and tie and felt hat.”8

Walker’s art tells a tale of two halves. Her many landscapes, still lifes, and portraits of friends and acquaintances—notably the artist Barbara Hepworth—were entirely the expected subject matter for women artists at the time, and it was thanks to these works, realized in an English Impressionist style, that she gained membership to the New English Art Club in 1900, becoming the first woman to do so. She represented Britain at the Venice Biennale four times, in 1922, 1924, 1928, and 1930, and was made an associate of the Royal Academy, London, in 1940. More unusual for the time, and most striking, are her monumental paintings of female nudes. Although she was particular about her models and how they looked when they sat for her—insisting they wear no makeup, especially no “filthy” lipstick—her nudes do not seem to represent people she knew.9 Rather, they stand for abstract ideas, such as the soul (Zone of Love, c. 1930–32), or for symbolic qualities, such as “Ecstasy” or “Aspiration,” that Walker would note down on the back of her drawings.

Around 1910, Walker began a long series of “decorations” featuring nude female figures set in golden-age scenes. Decoration: Evening is characteristic of this series, showing women who appear to be living in the kind of Sapphic community that lesbian artists and literati such as Nathalie Clifford Barney attempted to re-create in 1920s Paris. Evening features four nudes, two of them taking relatively naturalistic poses, two represented in a way reminiscent of ancient Greek sculpture, a feeling heightened by the classical triangular composition. Their idealized bodies glow in the soft dusk light, rendered by a desiring female gaze that nonetheless presents each woman as an individual with distinct physical features. The central figure in particular is represented with a poignant interiority—a far cry from a purely eroticized female nude.

—Eléonore Besse

Tarsila do Amaral

Paisagem com ponte (Landscape with Bridge, 1931)

“I invent everything in my painting. And I stylize whatever it was that I saw or felt,” said Tarsila do Amaral in an interview of 1972.10 She asserted this power of invention and reinvention as early as the 1920s through her involvement in Brazil’s Pau-Brasil and Antropofagia movements, of which Paisagem com ponte is an expression. Pau-Brasil— meaning “brazilwood,” the country’s national tree—revalorized Brazil’s native culture, invoked here by the lush colors of the local vegetation (palm trees, banana trees, agaves) and by the façades of pink, green, and blue houses, not to mention the gradations of blue of the sky, mountains, and lake. These nuances operate as a leitmotif in do Amaral’s Pau-Brasil series and appear in her work from 1924, when she spent a period in the Brazilian state of Minas Gerais, where her sensibility was influenced by popular Brazilian motifs and subjects. Following the Semana de Arte Moderna (Week of modern art), a festival of modern art, literature, and music in São Paulo in 1922, she turned from portraiture to concentrating fully on Brazilian landscapes, of which Paisagem com ponte is an example.

Do Amaral drew her modernist pictorial vocabulary from the avant-garde of Paris (where she lived from 1920 to 1922), notably Fernand Léger and Robert Delaunay. But she reinvented the language, as the ambivalence of Paisagem com ponte attests, with its tension between nature and culture. The two animals in the painting, with their chestnut color and elongated forms and curves, recall do Amaral’s pivotal Abaporú (1928; “Cannibal,” in the Tupi-Guarani language), and both works invoke the Brazilian aesthetic concept of antropofagia (anthropophagy), laid out by Oswald de Andrade, then do Amaral’s husband, in the Manifesto Antropófago of 1928. The concept of anthropophagy—in do Amaral’s and de Andrade’s thinking, the capacity of Brazilian art to absorb and digest external influences so as to invent its own language—translates into the irruption of the bridge in the painting. It occupies the foreground, and its industrial gray and black colors sharply contrast with the rustic landscape. It suggests a gateway that could represent the link both between the countryside and the modern city, where urbanization and industrialization were continuously accelerating, and between the two countries from which do Amaral drew inspiration, Brazil and France.

—Zélie Chabert

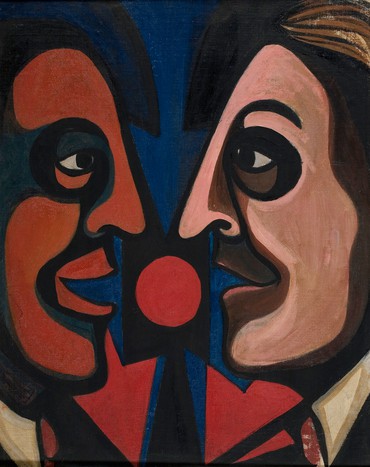

Faith Ringgold

Two Guys Talking (1964)

The US Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibited all types of discrimination based on race, color, and national origin. It was against this backdrop that Faith Ringgold found her artistic voice. An African American artist who was born in 1930 in New York, the epicenter of modern art in the second half of the twentieth century, Ringgold was the daughter of a Harlem fashion designer. As a child she was immersed in the worlds of culture and art, growing up in the wake of the Harlem Renaissance, a movement that fostered a sense of racial identity and pride among African Americans in New York and beyond.

Ringgold’s work is part of the movement that continued the cultural fight for the civil rights of African Americans but it also promotes the interests of another distinct minority, that of African American women. A turning point in her artistic career occurred when she was rejected for membership in the Spiral collective (1963–65), a group of African American artists, led by Romare Bearden, that included just one woman, Emma Amos. These dual focuses of activism are particularly evident in Ringgold’s American People Series (1963–67), which built on her Early Works (1960s), the series that includes Two Guys Talking. This painting shows two male heads in profile, outlined in black; they are engaged in conversation. The title is open to multiple interpretations. Is this a conversation between individuals of different skin colors, a negotiation of some kind, or an outright confrontation? A routine encounter or a vociferous political debate? Does the mask-like quality of the faces reveal a social dimension? The artist speaks to her use of a dark palette: “I work from the blacks and browns and grays that cover my skin and hair. My vision of myself necessarily extends to [the] colors of everything else in the world.”11 But if Ringgold is representing the Black community, where is the place and voice of women in this picture?

This conundrum seems to be addressed in Ringgold’s The French Collection Part 2: #11, Le Café des Artistes (1994), a painting with accompanying text that acts as a statement linking the conditions of African Americans and women. Standing amid a throng of artists including Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Maurice Utrillo, Paul Gauguin, Vincent van Gogh, Loïs Mailou Jones, Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller, Jacob Lawrence, Elizabeth Catlett, and Ringgold, Willia Marie Simone—a fictional character from the French Collection series—proclaims her Colored Women’s Manifesto of Art and Politics, “What is very old has become new. And what was black has become white. ‘We wear the mask’ . . . Modern art is not yours or mine. It is ours.”

—Zélie Chabert

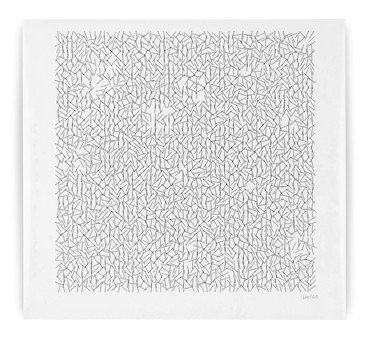

Vera Molnár

Interruptions (1968)

A graduate of Budapest’s Hungarian University of Fine Arts, Vera Molnár moved to Paris in 1947, fascinated by Cubism and drawn to the city that she viewed as the epicenter of the artistic avant-garde. There she met Sonia Delaunay (“the goddess of abstract art,” in Molnár’s words), who encouraged the younger woman to pursue her studies.12 She also collaborated with other artists of her generation, including François Molnár, whom she later married, and members of the artist’s group the Centre de recherche d’art visuel (CRAV, later renamed the Groupe de recherche d’art visuel, or GRAV), participating in their explorations of collective artistic creation.

Molnár’s visual vocabulary is closely related to geometric abstraction but her experimental approach involves trial and error, exploring scientific methodologies while at the same time calling their assumptions into question. She believes that this approach reveals the inconsistencies and random elements that occur within planned, rational systems, “forcing a questioning of the uncertainty that governs our entire life, our thoughts, memory, everything.”13 For the French critic Anne Tronche, her work entails “judgments about the vulnerability of the right angle.”14 With this idea in mind, Molnár’s art may be considered from a humanistic perspective.

Following preliminary experiments with an “imaginary machine”—making drawings by hand but basing them on computer programs—Molnár introduced the computer directly into her creative process. She delegated the execution of her artworks to these machines, thereby reinforcing her commitment to producing works in series. She did not entirely abandon the principle of randomness, however, and deliberately injected “1 percent of disorder” into the systems that she created. In 1968–69, she began the series Interruptions, a group of drawings whose structure is based on a grid pattern. The square surface of the support is covered with a fine web of identical rectilinear strokes to which the artist gives different orientations. Molnár accentuated this dynamic effect by including, or rather subtracting, empty spaces—“interruptions”—that introduce spontaneous elements into the composition.

The art historian Rosalind Krauss sees the grid as an archetypal form of “modern artistic production,” and Molnár’s work can be interpreted as an irreverent homage to the geometric abstractionists of modernism, particularly Piet Mondrian and Kazimir Malevich.15 She refers to them explicitly in some series, including an ensemble based on the letter “M.” Here, empty spaces evoke both eradication and the potential for a new beginning for an artist who describes herself as “a Conceptualist who likes to execute, who likes to see the work getting done.”16

—Matylda Taszycka

1Dr. Clare McAndrew, The Art Market 2023: A Report by Art Basel and UBS (Basel: Art Basel; Zurich: UBS, 2023). Available online at https://www.ubs.com/global/en/our-firm/art/collecting/art-market

-survey/download-report-2023.html?campID=NL-ANY-GLOBAL

-ENG-ANY-ANY-ANY (accessed July 12, 2023).

2Julia Halperin and Charlotte Burns, “Introducing the 2022 Burns Halperin Report,” artnet news, December 13, 2022. Available online at https://news.artnet.com/art-world/letter-from-the-editors-introducing-the-2022-burns-halperin-report-2227445 (accessed July 12, 2023).

3See bell hooks, Art on My Mind: Visual Politics (New York: New Press, 1995); Adrian Piper, “The Triple Negation of Colored Women Artists,” 1990, in Hilary Robinson, ed., Feminism-Art-Theory: An Anthology, 1968–2000 (Malden, MA: Wiley, 2001), 57–67; Harmony Hammond, Lesbian Art in America: A Contemporary History (New York: Rizzoli, 2010); and Renate Lorenz, Queer Art: A Freak Theory (New York: Columbia University Press, 2018).

4Halperin and Burns, “Introducing the 2022 Burns Halperin Report.”

5Griselda Pollock, “The Missing Future: MoMA and Modern Women,” in Cornelia Butler and Alexandra Schwartz, eds., Modern Women: Women at The Museum of Modern Art (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2010), pp. 28–55.

6Lucy R. Lippard, “Sweeping Exchanges: The Contribution of Feminism to the Art of the 1970s,” Art Journal, Fall/Winter 1980, p. 362.

7Virginia Woolf, The Sickle Side of the Moon: The Letters of Virginia Woolf, ed. Nigel Nicolson and Joanne Trautmann (London: Hogarth Press, 1979), p. 5:174.

8Emmanuel Cooper, The Sexual Perspective: Homosexuality and Art in the Last 100 Years in the West (London and New York: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1986), p. 108.

9See Lilian Browse, Introduction to Distinguished British Paintings 1875–1950: An Accent on Ethel Walker (London: Roland, Browse & Delbanco, 1974).

10Tarsila do Amaral, in Leo Gilson Ribeiro, “Entrevista Tarsila do Amaral,” Veja 181 (February 23, 1972): pp. 3–6.

11Faith Ringgold, quoted in Mary Walker, “Artist-Lecturer Cites Women as Thrown Out with the Riot,” Daily Reveille, October 5, 1973.

12Vera Molnár, in Vincent Baby, Interview with Vera Molnár (Paris: AWARE, 2022), p. 39.

13Ibid., p. 42.

14Tronche, quoted in ibid.

15Rosalind Krauss, “Grids,” October 9 (Summer 1979): p. 50.

16Molnár, in Baby, Interview with Vera Molnár, p. 54.

Texts by Zélie Chabert and Matylda Taszycka, translated from the French by Molly Stevens