Harry Thorne is a writer and an editor at Gagosian. He lives in London.

I like living, breathing, better than working . . . my art would be that of living.

—Marcel Duchamp, in Pierre Cabanne, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, 1971

D’ailleurs c’est toujours les autres qui meurent (Besides, it’s always the others who die).

—Epitaph on Marcel Duchamp’s tombstone, Rouen, France

Beat 1

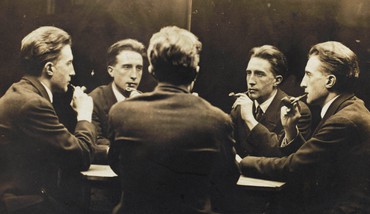

On April 6, 1966, Brian O’Doherty and his wife, Barbara Novak, hosted a dinner for Marcel Duchamp. Invitations were extended to Teeny, Duchamp’s wife; Parmenia Migel Ekstrom, a ballet historian and author; Arne Ekstrom, an art dealer and Parmenia’s husband of thirty-three years; and the gallerist Richard Feigen. But it was Duchamp who, figuratively at least, was seated at the table’s head. In his honor, Novak brought down a copy of Julia Child’s Mastering the Art of French Cooking, volume 1 (1961), and assembled a suprêmes de volaille aux champignons, a rich dish of chicken and mushrooms swimming in a cream sauce. Unsympathetically, she followed this with an English trifle. “Duchamp looked at this high-cholesterol extravaganza and demurred,” O’Doherty would recall. “He may have thought it was an attempt on his life.”1 (Duchamp ate everything.)

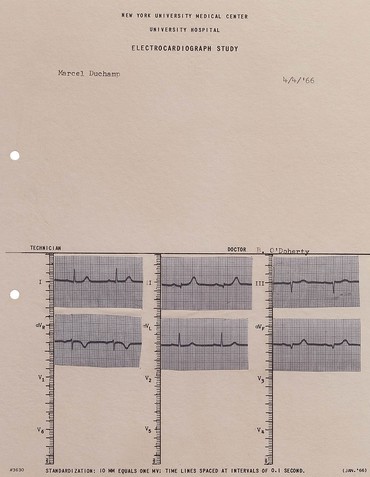

Once the plates had been cleared, O’Doherty invited Duchamp into the bedroom and asked him to remove his shirt—a questionable request fulfilled without question. Duchamp was then instructed to remove his shoes and socks, hike his pants to his shins, and lie on his back. “If I had said I was going to take out his heart,” O’Doherty later wrote in an account of the evening, “I suspect he would have been mildly curious as to how I was going to go about it.”2 With his patient in place, O’Doherty applied an electrode gel to his wrists and ankles, attached to them the cold metal leads of a rented electrocardiograph machine, and proceeded to take a series of readings of Duchamp’s heart. As the machine’s inked needle juddered its recordings onto an unfurling reel of gridded paper, the pair observed in silence. Duchamp lay unmoving, still, as the procedure ran its course. “How am I?” he asked, as O’Doherty gathered his readings, his proof of life. “Thank you,” he followed up, buttoning his shirt, “from the bottom of my heart.”3

Beat 2

An electrocardiogram (ECG or EKG) records the heart’s electrical activity. A single heartbeat appears as a wave, a swift burst of energy that, when scrutinized, reveals three smaller bursts collectively termed PQRST. Each PQRST segment corresponds to a different part of the contraction cycle. The P wave, which on a recording reads as a shallow lift, shows the depolarization of the heart’s upper chambers, or the atria. The QRS complex, often the most dramatic upward spike on a reading, represents the subsequent depolarization of the left and right ventricles, while the T wave, a second slight elevation, shows their repolarization. As we move through the P and QRS waves, we open up our hearts. With T, they slam shut once again.

ECGs are an old technology—the first electrocardiogram, conceived by the Dutch scientist Willem Einthoven, was constructed in 1911; it weighed 600 pounds and required a team of five operators—but they remain in constant use today. The heart contracts in a specific and orderly fashion: one chamber followed by the next, and the next, to ensure the smooth passage of blood. These contractions are organized by an electrical flow, one regulated by the opening and closing of sodium- and potassium-ion channels. If you attach leads to the extremities of the body and to the chest wall, you can track the direction of this electrical flow. Placing these leads in different positions around the body allows you to view this flow from various perspectives. If electrical activity is surging toward the lead, the reading will carry a positive inflection. If it is retreating, the inflection will be negative. ECGs allow us to glimpse every angle of the heart’s beat, to hear every tone of its voice.

Beat 3

O’Doherty completed a medical degree at University College Dublin in 1952 before relocating to Boston in 1957 to study at Harvard. In 1958, shortly after receiving his MSc, he abandoned science and became the writer and host of Invitation to Art, a local public-television show, as well as an artist and critic. He would later become an art writer for the New York Times, editor-in-chief of Art in America, and, for nineteen years, director of the film, radio, and television section of the National Endowment for the Arts. In 1967, O’Doherty commissioned Roland Barthes’s key poststructuralist text “The Death of the Author” for issue 5+6 of Aspen magazine, which took the form of a conceptual-exhibition-in-a-box and also included Susan Sontag’s “The Aesthetics of Silence”; in 1976, he wrote Inside the White Cube: The Ideology of the Gallery Space, an era-defining essay on the commodification of art that fundamentally altered our thinking around the sociology, economics, and aesthetics of art galleries.

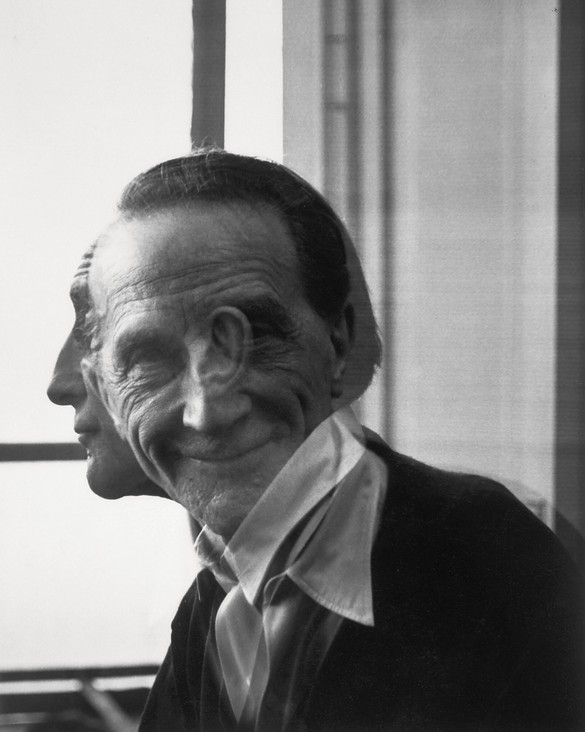

But from his earliest years in the United States, O’Doherty actively pursued Duchamp—as many have, as many will. (“I went from Boston to hunt him down,” he later said, validating the predatory edge of this sentence.)4 At that point, in the late 1950s, Duchamp was not a household name. John Cage, Robert Rauschenberg, and Jasper Johns were familiar with his work and were supportive, but he had yet to achieve the status of trickster god, of art world immortal. Indeed, in 1965, having left the New York Times for Newsweek, O’Doherty pitched an article in which he made the then audacious claim that, following Pablo Picasso, Duchamp would be remembered as the most significant artistic figure of the twentieth century. The article was rejected, deemed hagiographic in the extreme. O’Doherty resigned his post in protest.

The pair’s early interactions were tense, tentative. During their first meeting, at Duchamp’s home in New York in 1959, O’Doherty attempted to persuade him to appear on Invitation to Art. “Words,” Duchamp responded, with perceptible glee, “words don’t do anything.” He continued, relishing his own digression: “We are in the bath trying to explain the bathwater. We can’t tell ourselves from the bathwater.”5 Despite the pointed inscrutability of this statement, the pair became friends. Duchamp was, to O’Doherty, fascinating, impregnable, untouchable. He was uniquely skeptical of the purported sanctity of art. He was a fellow chess devotee. He was one of few who in O’Doherty’s eyes reached the dizzying level of James Joyce—“a brilliant man, for a writer.” “I felt that Duchamp is red-hot,” O’Doherty said, in a rare foray into the figurative, “and if you touch him, you get burned. So white-hot is, perhaps, better.”6

Beat 4

What did he want to see, when he peered into his friend’s heart? What did he want to find, record, tend to? On December 3, 1967, in Cape Town, Christiaan Barnard completed the first human-to-human heart transplant, transferring the heart of a twenty-five-year-old woman fatally injured in a car accident into the chest of a fifty-three-year-old grocer who was dying from chronic heart disease. O’Doherty, like Duchamp, was fascinated by the encroachment of the machine into the realm of man (or vice versa). For him, Barnard’s groundbreaking surgery claimed dominion over the beating heart, and, in doing so, reanimated the age-old conflict between poetry and science, between mystery and method. (Between what John Keats, Charles Lamb, and Benjamin Haydon drank a toast to in 1817: “confusion and mathematics.”)7 “In the light of the transplantable heart,” O’Doherty wrote in 1969, “does not the history of poetry, as Keats would have suggested, become strewn with ruined metaphors?” He persisted: “We find Dr. Barnard’s scalpel separating two ages from each other, and calling the specters of what we might call identity past and identity future to confront one another across a division called consciousness.”8

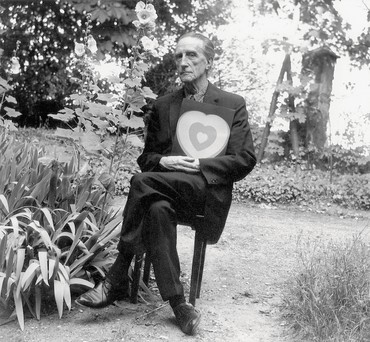

Duchamp’s heart represented more, to O’Doherty, than a convenient battleground for these specters. This heart had tales to tell. “A picture,” Duchamp mused with frequency throughout his life, “a work of art, lives and dies just as we do . . . it lives from the time it’s conceived and created, for some fifty or sixty years . . . and then the work dies.”9 (At his most fatalistic, he gave it just twenty years to live.) For Duchamp, a work existed while it was coeval with its audience. When said audience—and, by association, the lived context and conditions of that work’s creation—passed, so too was the work relegated to the archive of art history. (And as he reiterated, wisely or otherwise, “art history is not art.”)10 For Duchamp, the museum was a palliative-care ward, a comfortable space for ideas not long for this world, an inevitable death under sympathetic lights. “As a drug, it’s probably very useful for a number of people,” he said of art’s momentary release, “but as religion it’s not even as good as God.”11

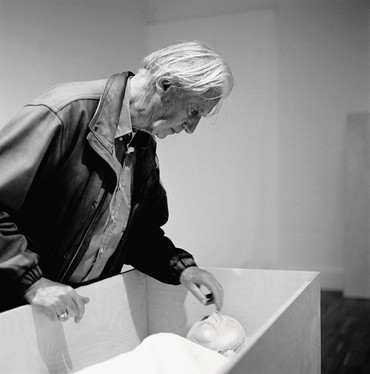

O’Doherty distributed Duchamp’s ECG into sixteen cardiogram readouts, preparatory drawings, and homemade oscilloscopes, which he collectively titled Portrait of Marcel Duchamp and exhibited periodically for years to come. In hanging (symbolically and literally) the still-beating heart on the whitewashed walls of the gallery—Duchamp’s purported mausoleum—he offered a pointed, poignant, and irrefutably funny rebuttal to the notion that artworks are mortal beings. His portrait would not condemn its subject to some fifty or sixty (or indeed twenty) years, but rather enact a magical stretching of time, drawing out Duchamp’s body, his place, his moment, and ensuring that he would exist in and as more than one thing at once. A fragmentation, a redistribution, a protraction—a safeguarding against the inexorability of human mortality. “He had given me my readymade,” O’Doherty recalled of his companion’s sacrifice, “his heart had made a readymade. . . . But that wasn’t good enough. I wanted him live. I wanted him alive.”12

Beat 5

Both Duchamp and O’Doherty were shape-shifters. In their lives and their respective practices (if it is responsible to separate the two), they each took great pleasure in contradiction, disintegration, and self-reinvention in the face of convention. (“Nothing fits a priori into a fixed context,” Michel Sanouillet wrote of Duchamp; “poor zeitgeist,” O’Doherty once teased.)13 And so too did their identities slip and fall with sumptuous ease. In 1972, Duchamp found a second self in his beloved alter ego Rrose Sélavy, a pun on “Eros, c’est la vie” (Sex, that’s life). O’Doherty was intermittently the linguist Sigmund Bode, the art critic Mary Josephson, and the poet William Maginn, a name shared by a character in his novel The Deposition of Father McGreevy (1999), for which he was nominated for the Man Booker Prize. Most faithfully, he was the artist Patrick Ireland, an identity he adopted in 1972 following the murder of fourteen Ulster civilians by the British army on what would become known as Bloody Sunday. O’Doherty pledged to retain this unambiguously symbolic name until the British withdrew troops from Northern Ireland. On May 20, 2008, in recognition of their evacuation, he attended his own funeral, burying Patrick Ireland “with the hatred that gave rise to him.”14

There is no one true self: no pure being. We are all, to our own extents, Duchamp and O’Doherty, discovering and discarding our selves as we go. (“Most people are other people,” Oscar Wilde wrote, with knowledge of the topic.)15 One should not misconstrue Portrait of Marcel Duchamp as an act of homage alone. But in peering into Duchamp’s chest, in attempting to locate a lambent charge that could not be concealed or confused or made wholly new again, O’Doherty betrayed a desire to capture, for want of a better word, an essence. To get to the heart of things—not as a means to disavow or discredit what occurred externally, but to understand it. To know it, with clarity and care. To be with it, just for a beat. “I studied that heartbeat,” O’Doherty said, with such delicacy. “I drew the first lead, with its big T bump, very carefully. I wanted to become intimately acquainted with it.”16 But that wasn’t good enough. I wanted him live. I wanted him alive.

Beat 6

O’Doherty and Duchamp never discussed the heartbeat, nor the lives that it lived beyond its donor’s chest. But during the private view of O’Doherty’s first exhibition, at the Byron Gallery on Madison Avenue in 1966, which included a cardiogram and a series of accompanying drawings, Duchamp turned up. O’Doherty watched as the show’s muse crossed the threshold, crossed the room, and paused in front of his own heart. (“I was reminded,” O’Doherty said, “that Eugène Delacroix apparently said he hadn’t understood [J. M. W.] Turner’s paintings until he saw John Ruskin looking at them.”)17 And he watched, still, as Duchamp turned, pondered a nearby illustration of a chess problem, and left. O’Doherty may have perceived Duchamp’s reserve as disinterest—or, more damning still, distance. But unbeknownst to him, Duchamp held on that evening to a small piece of paper folded in his pocket. It read, as his tombstone in Rouen would read just two years later, D’ailleurs c’est toujours les autres qui meurent (Besides, it’s always the others who die).18

“Did he realize,” O’Doherty asked once the namesake of Portrait of Marcel Duchamp passed, “that [the work’s] true existence would begin when he had departed?”19 And did O’Doherty, when he himself departed in 2022, realize that this question—of life, death, and its supporting cast; of remembering and forgetting; of portraiture—would reach farther still? When Duchamp died, O’Doherty calculated the allocated quota of heartbeats in his lifetime. Connecting an oscilloscope to a small motor purchased on Canal Street, he reduced their speed, slowing them to a mere seven beats per minute. “When you divided seven into the number of lifetime heartbeats,” he wrote, “I could make him live two hundred years.”20 How to make our loved ones live one, two, three hundred years? How to make our loved ones live—not again, but on? Look into them. Trace their hearts. Hang them on the wall. “I felt that I had Duchamp’s secret,” O’Doherty said to an assembled audience in 2009. “And in a curious way, I felt that he had brought me to reveal much of my own.”21

1Brian O’Doherty, “Taking Duchamp’s Portrait,” 1966, in Collected Essays (Oakland: University of California Press, 2018), p. 244.

2Ibid.

3Marcel Duchamp, quoted in ibid.

4O’Doherty, in ibid., p. 241.

5Duchamp, quoted in ibid.

6O’Doherty, in James W. McManus, “Oral history interview with Brian O’Doherty, 2009 Nov. 16–17,” Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, 2009. Available online at https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-brian-odoherty-15746 (accessed February 26, 2023).

7See O’Doherty, “The Politics and Aesthetics of Heart Transplants,” 1969, in Collected Essays, p. 99. If O’Doherty’s belief in the equal merit of science and art was ever in doubt, his subtle misquoting of this fabled toast alters its original meaning to support his view. The assembled group of Romantics, which also included William Wordsworth, were scornfully discussing Isaac Newton, who, Lamb believed, “had destroyed the poetry of the rainbow by reducing it to a prism.” Their glasses were raised not to “confusion and mathematics” but, facetiously, to “Newton’s health, and confusion to mathematics.”

8Ibid., pp. 105–6.

9Duchamp, in Jean Antoine, “Life is a game; life is art,” Art Newspaper, March 31, 1993. Available online at https://www.theartnewspaper.com/1993/04/01/life-is-a-game-life-is-art (accessed February 26, 2023).

10Duchamp, in George Heard Hamilton, Richard Hamilton, and Charles Mitchell, “A 1959 Interview with Marcel Duchamp: The Fallacy of Art History and the Death of Art,” 1959, Audio Arts, 1974, transcript in Artspace, February 21, 2018. Available online at https://www.artspace.com/magazine/art_101/qa/a-1959-interview-with-marcel-duchamp-the-fallacy-of-art-history-and-the-death-of-art-55274 (accessed February 26, 2023).

11Duchamp, quoted in Calvin Tomkins, “Not Seen and/or Less Seen,” New Yorker, February 6, 1965, p. 40.

12O’Doherty, in McManus, “Oral history interview with Brian O’Doherty.”

13Michel Sanouillet, Introduction, in Duchamp, The Essential Writings of Marcel Duchamp, ed. Sanouillet and Elmer Peterson (London: Thames and Hudson, 1975), p. 9; O’Doherty, “Strolling with the Zeitgeist,” Frieze no. 153 (March 2013). Available online at https://www.frieze.com/article/strolling-zeitgeist (accessed February 26, 2023).

14O’Doherty, in “Brian O’Doherty with Phong Bui,” Brooklyn Rail, June 2007. Available online at https://brooklynrail.org/2007/6/art/doughtery (accessed February 26, 2023).

15Oscar Wilde, De Profundis (London: Methuen, 1905), p. 83.

16O’Doherty, “Taking Duchamp’s Portrait,” p. 244.

17O’Doherty, “Strolling with the Zeitgeist.”

18See McManus, “‘Portrait of Marcel Duchamp, 3 Leads’ by Artist Brian O’Doherty, Face-to-Face Talk,” National Portrait Gallery, podcast, July 7, 2009. Available online at https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/portrait-marcel-duchamp-3-leads-by-artist-brian-odoherty/id312570523?i=1000056408414 (accessed February 26, 2023).

19O’Doherty, “Taking Duchamp’s Portrait,” p. 248.

20Ibid., p. 249.

21O’Doherty, speaking at the symposium “Inventing Marcel Duchamp: The Dynamics of Portraiture,” National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, July 17, 2009.