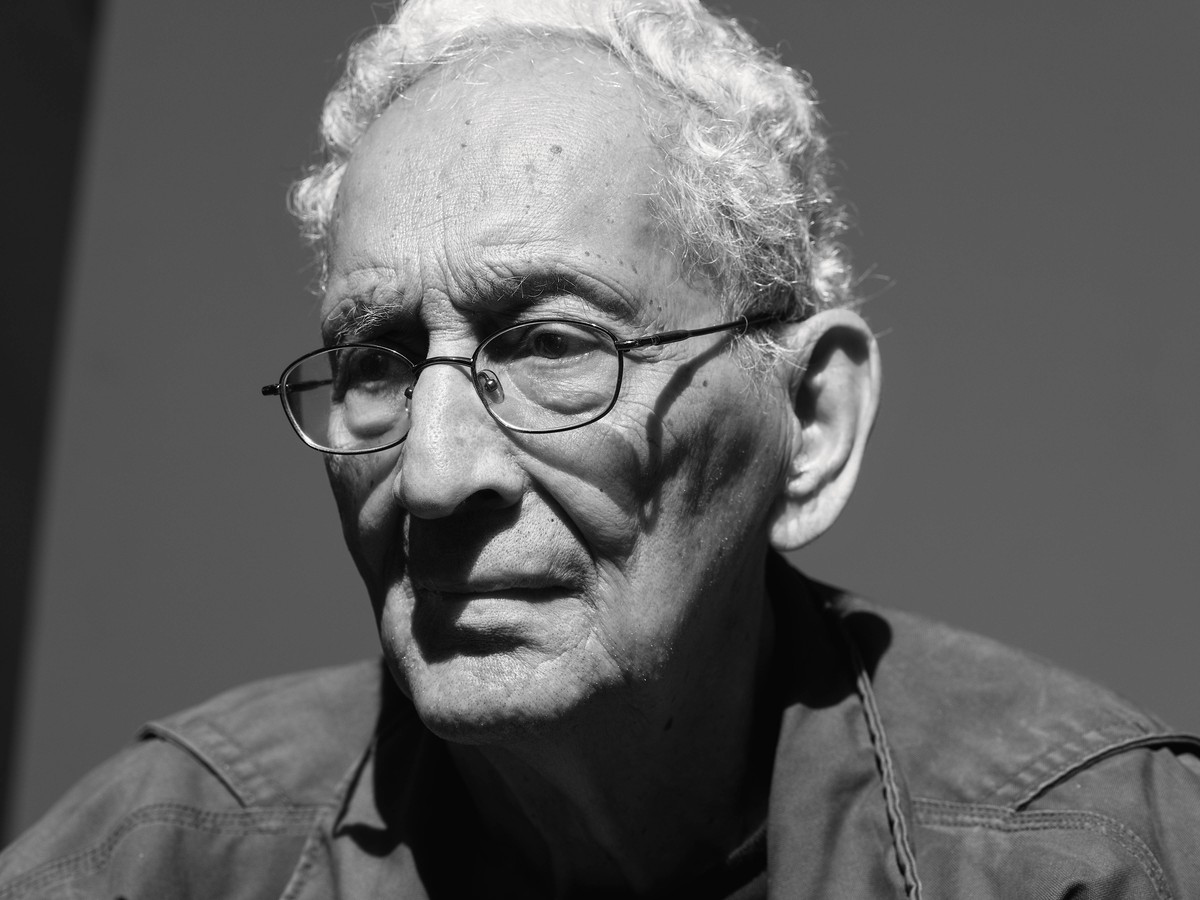

Megan Kincaid is an art historian and curator. Kincaid has taught on modern art and critical theory at New York University and her scholarship has been published by the Museum of Modern Art, Duke University Press, and others. In May 2024 she will receive her PhD in art history from the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University. She holds a BA from Columbia University.

Megan KincaidI know you’ve just left work in your studio and have numerous projects underway, but I wanted to start at the beginning. You’ve lived in New York since 1958, right after you graduated from Princeton. Do you consider yourself a “New York artist,” or an “American artist” for that matter? In 1958 those designations were significant—they announced the new artistic vanguard working against European tradition.

Frank StellaI wanted to try to see if I could support myself. It was a pretty straightforward idea about being a New York artist. There wasn’t any doubt about that. And that was what the style was, everybody else was a New York artist, too. I think you came to New York because that was where the art you were interested in or cared about was being made. And it was all New York artists, there just wasn’t any question about it. That was where all the artists were exhibiting; the work was being shown all the time there. And you have to remember one thing too about being an artist and being young: the art was available, and it was free. You could go around to galleries and museums and that was it: everything was being shown and you could be part of it.

MKBy that time, Abstract Expressionism was supposedly on the decline—Minimalism and Pop were steadily coming into view. Did you sense a shift?

FSNo, I didn’t see the decline. It’s hard to say, it was all one thing. What were you going to say—Jasper [Johns] and Bob [Rauschenberg] weren’t Abstract Expressionists? There’s a lot of Abstract Expressionism in Pop art. By and large what was going on was pretty much the same. What the emphasis was or how it came out normally wasn’t that surprising.

MKYou were also all exhibiting at the same galleries.

FSOr drinking at the same bar.

MKThe Cedar Tavern. Were those nights quite fun?

FSThey weren’t boring.

MKIn the Black Paintings [1958–60], considered your breakout series, the compositions are comprised of repetitive concentric lines following the shape of the canvas. You have said that the focus on line was in some ways a continuation of Jackson Pollock’s drip paintings, though in a more austere language. Did you understand this body of work to be a departure?

FSI didn’t think of it as any kind of real break or anything. I was looking, I guess, to do something that was just a little bit less bound up and less gestural without being totally “abstract,” as they say. I was looking for a little bit of each.

MKYou were part of a very ambitious cohort, too. You describe other artists as constantly “invading” your space.

FSYou needed somebody to be with you a little bit. It was just to feel you were working on something and had something to do. It was a sense of belonging, you know—that was the main thing. You had a job, somewhere to support yourself, and you had a life with your friends. It was pretty loose. Since I was young then, everyone else seemed young, too. You could say it was a pretty childish environment.

MKNot too many adversaries, then?

FSWell, you know there’s that story, I got it from Carl [Andre] but I’m sure it’s true, you know, arguing with [Franz] Kline about how you know a good artist, or what’s a good young artist. And Franz said, “You know, it’s easy, you take them off the stools here in bars and you lift the grate off the sewer out there and you throw ’em down the sewer and then put the grate on top. The one who crawls out first is the best artist.”

MKThis sort of macho rhetoric of American art at mid-century is heavily contested today in terms of the inclusivity of these movements—do you feel that’s an accurate assessment of that time, that it was a boys’ club?

FSI guess so. There were girls there too. It was pretty loose, and what seems surprising to me looking back a little bit is how self-contained it was; everybody was pretty confident about what they were doing somehow. To be honest I knew what everyone was doing and it was kind of, it seems silly now and everything, but you either liked it or you didn’t and you didn’t worry about it. I was pretty happy with most of the painting that I saw.

MKReconstructing this social context, you were involved in the political and social revolutions of the 1960s. Looking retrospectively, you can see certain changes occurring: you break out of a limited palette into a vivid color spectrum, and the shaped canvases beginning in 1966 directly interrogate “real” space. These formal changes might be evaluated as indexes of social consciousness, liberation, radicalism.

FSI think they should have been, but not very much, because you took all of that for granted. You went to a march, or you gave a print to this cause or that cause, but it was really just something you did and went on with. At some point it got to be ridiculous. There was a crackdown on the guys in prison so everybody had to do something to help out with prison reform; I made a poster and they complained it didn’t have enough color in it. So you can see where we were.

MKYou’re heralded as a forefather of Minimalism. Part of that legacy unfurled from your now axiomatic statement on artistic literalism: “What you see is what you see.” Do you still feel that way?

FSYeah, unless you can show me something else. I don’t know what happened or what it was; it was a pretty casual remark! Donald Judd was doing this reverse criticism about the kind of thing that goes on in Europe, where you’re always talking about the meaning of the work, and they would tell you what’s in the painting and I couldn’t see it. But they probably did. That’s what’s actually kind of interesting about it.

MKFor you, then, is meaning always interpretive and open? You often attach clear titles to your abstractions, directed to literature or places.

FSWhen you start looking at what you’re looking at, you can go anywhere.

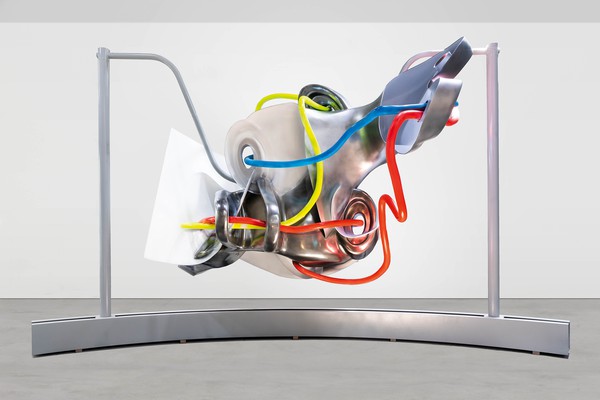

MKOvert figuration often entails a degree of didacticism. Yet when you pull in concrete references in your recent sculptures—stars, smoke rings, rivers, hotels—it’s always in oblique ways.

FSI see the world pretty much the way everyone else sees it, but I’m not driven to represent it very much.

MKYou’ve used technology to stage imaginative form on a monumental scale that encroaches on reality itself.

FSThat may be true. I have people who help me. You know, I think of maybe a Rubens painting when the guy comes in to paint a lion. There’s a level of technology in fabrication, and when you’re working in the foundry and actually making the thing, that’s pretty interesting. If I learned anything, that’s the way I learned most of it. The part about making something, or the fabrication—you have to go back to the technology to give the fabricators the information they need. It’s like doing your geometry lesson: you’re not doing so well, so you’ve got to get a tutor. A lot of artists were able to do what they wanted; they were artisans as well as artists. A lot of them, like David Smith, came from a job—he’d been a welder.

MKThere’s an amazing room in your studio filled with dozens of maquettes—is there anything you have pegged to realize on a large scale?

FSThere are quite a few models; most of them will get a little bigger. You go from small to medium to large. Small is a little tough, in a way, but I like that. Then medium is pretty good. And then I have to decide which ones I want to go large with. Since you’ve been working on them for quite a while, you have a sense of the ones you sort of like a little better than the others, or that you want to pursue. Sometimes you pursue ones that you think might just be too tough for you, so you get brave and try to do it.

MKYou refer to confronting “problems” that artworks present. Is art fundamentally agonistic? This seems ingrained in the Sisyphean tasks you set up for yourself—like making a work for every chapter of Melville’s Moby-Dick [1851].

FSThat just happened. If I hadn’t gotten annoyed at my son Michael, I wouldn’t have done that. He said “You don’t have to do all of the chapters,” as though I couldn’t figure that out for myself.

It’s the quickness of the hand. The hand and the eye. That’s what makes art: the flow.

Frank Stella

MKBut you’ve always worked in series.

FSYeah, I’m trying to think. . . . The ones I’ve not done as a series are pretty small. It has to do with the flow of the work—where you are, who you are at the time. I don’t think that much about it. My experience has been that what makes the work function is what gets attention. The work strikes you and it makes you pay attention to it somehow.

MKThe work’s ability to grab attention suggests that it possesses an agency, even an attitude. You have quite a sense of humor—do you think your sculptures can communicate that?

FSEvery once in a while, things just seem so obvious and so right and so good. But often with those pieces you come back to them or never get away from them, one way or the other. And then some things seem sort of dopey, but that’s usually because you don’t know enough about them. But then I suppose things could get even dopier if you explored them a little bit more. But that’s the way it is: you have to make something.

MKDo you mind the ones that are dopey?

FSNo, everyone seeks amusement.

MKYou know, when people see works like Smurf Hotel [2019], they immediately smile.

FSOh, that’s good. I like to stay away from my work when it’s being viewed. I remember Bob Rauschenberg videoing the people who were looking at his paintings.

MKIn his Aesthetics [1835], Hegel said the pitfall of modern art is its penchant for self-reflexivity—it was becoming art about the art, or art about the text. Against that tendency, in the 1960s you said that you wanted to make art that “couldn’t be written about.”

FSOoh, yeah. I was a bad boy. But you know, I wasn’t very successful; you can take that any way you want.

MKWell, exactly. You ended up being written about extensively.

FSI guess it’s just a question since the word “formalism” has gotten such a bad name, as they say. If it’s “just about itself,” it sounds like everything else has been excluded. But you can say it being just about itself and in the same breath including everything else there is to include.

MKThat gets to the imaginative possibility of formalism—that inventing around form moves beyond your surroundings.

FSYes, but with form, somehow you don’t know how you picked it. Once you start with it, you have to keep going. It’s pretty much as complicated as making something look like what you’re seeing, like when someone is sitting in a chair in front of you. I also think that the painters and things I like, although they are often very different, people get into it. Take Ed Kienholz: there’s a lot of stuff there but it’s also so much about how it’s put together. And you look at it at the end, but there’s hand-eye stuff that happens really quickly. And you don’t get it and you don’t really care—because he did it for you and you look at it after. It’s not as obvious as it seems. When you think of Kienholz, I think of Rauschenberg and the Combines [1954–64]. It’s the quickness of the hand. The hand and the eye. That’s what makes art: the flow.

MKAre scale and spatiality also important for that flow in which the subjects of art can act upon each other?

FSI guess it’s true. A little while ago I would have had an answer for that, since I made a lot of things when it was quiet in the pandemic and then when I was sick I made a lot of small pieces, collages, and they’ve been received quite well. But I can’t go back to them. Not yet. Between my hand and my eye, I see things, I think about it, I could do this or that. But it just doesn’t happen. I don’t know how to explain those kinds of things.

MKSo there’s an immediacy to your actions and compositional decisions that can’t be broken down or explained, and probably shouldn’t be!

FSI won’t argue with you!

MKOn the topic of quickness: two of your passions are race cars and horses—both very fast, both possessing very elegant movement. Were you always attracted to that dynamism?

FSI’m afraid to say it, but games and sports and that kind of physicality were a big part of my upbringing. So I suppose you can say that for me, making art remains a childish activity. I was doing wrestling and lacrosse. My father was a world-class wrestler in his time, so that was kind of tough, because I was being coached, but I liked it. It was tough when you were trying to outmaneuver your father; as I used to say, he was not only stronger than I am, but probably smarter. It was always competitive no matter what level it was at. My mother painted with me right from the beginning. Like painting Santa Claus on the window during Christmas. She was an artist. She went to fashion school in Boston.

MKAre you competitive—maybe not with other artists but with yourself? Has that been part of your engine or ethic?

FSIt’s the only streak I have. Without a competitive streak, I’d just stay asleep.

MKBeing in a household that wasn’t totally adulatory might have helped cultivate that?

FSIt was way more than that. All the activity was really physical and rewarding in itself, and kept you busy. It had a goal. What more can you ask for?

MKYou remain so active; you often go salmon fishing. What do you get from those trips?

FSI think it’s just from the beginning with my father—starting at the time I was eight or ten years old, we went on trips together. That was a little different with my father because he had a more structured life, so leaving for vacation was really a break for him. He was a gynecologist, obstetrics and gynecology.

MKDid he embrace your career as an artist?

FSAs I said, it was a silly, competitive family [laughs]. No, as long as I didn’t hit them up for too much money, they weren’t too hard on me. They went to everything.

MKIn 1970, you were thirty-three when you had your first retrospective, and it was at the Museum of Modern Art [New York] no less. How did you process that achievement?

FSIt wasn’t a problem for me. It wasn’t so much about me—I guess it was partly about me, but I didn’t have a problem because [the curator] Bill Rubin was so straightforward, a kind of mentor: whatever Bill said, okay. I didn’t worry about it.

MKSome artists recollect that after major retrospectives they feel the need to change direction.

FSI think I changed a bit after. I just move along. The main thing is looking at what you do as much as anyone else does. When you get tired of looking at it, you can start thinking about doing something else.

MKDid you ever have to reconcile your public image and your daily life?

FSI was busy. There were a lot of things—the kids, everyday life. And the paintings seemed to fit into the middle of the day.

MKJust like a nine to five.

FSMore like it was ten to four, or a ten to three.

MKThere’s a tendency to romanticize the way artists live, how they dress and self-fashion. Like the fixation on the three-piece suit that you wore in the MoMA Sixteen Americans catalogue [1959], since you appeared so buttoned up.

FSYeah, that was because Hollis Frampton took the picture that they requested for the catalogue. We never gave it any thought; I thought it looked nice and so we sent that in. And then Dorothy Miller, who curated the show, called and said, Didn’t I have a more informal photograph?

MKYou’ve previously said that your formation as an artist was determined by the fact that you were born in 1936. Nearly ninety years later, do you still feel those ties to the past?

FSNo, you know, I’ve been here so long. But I guess I’m a Northeast product of something. New York is where you can see art. If it’s something you’re using to support yourself, you have to be here, or recognize it in a very serious way.

Artwork © 2024 Frank Stella/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York