Corey Keller is an independent historian of photography based in Oakland, California. From 2003 to 2021, she was a photography curator at SFMOMA, where her critically acclaimed exhibitions included Dawoud Bey: An American Project (2020; co-organized with the Whitney); Signs and Wonders: The Photographs of John Beasley Greene (2019); and Francesca Woodman (2011).

Putri Tan joined Gagosian in 2006 and is a director based in New York. She manages a number of the gallery’s artists, among them, Harold Ancart, Walton Ford, Sally Mann, Spencer Sweeney, and Francesca Woodman.

Putri TanCorey, the exhibition you curated at SFMOMA in 2011, Francesca Woodman, provided a broad retrospective view of her work, which was necessary because a great number of those photographs hadn’t been widely seen in the United States for about twenty-five years. Many of your selections were lesser-known works that offered new insight into Francesca’s art and interests. I wonder if today you feel there are still overlooked areas of Woodman’s work, or whether there’s a specific focus you would explore if you were to curate an exhibition anew?

Corey KellerAt the time of that exhibition, Francesca hadn’t had a major survey in the United States. Nonetheless, a whole mythology had already attached to her work. The way it was talked about was not only defined by a body of scholarship but was also deeply informed by her biography. I felt like I had a responsibility to try to complicate those readings a little bit and to take a more expansive look at her practice. She was such a young artist, it was hard to decide where her “serious” work began. I chose not to include the work she did when she was still a high school student in Colorado, although I did write about it in the catalogue essay. I started with her time as an undergraduate at RISD, which is probably her best-known work. But I wanted to give a sense of the scope of her photography, not just the incredible work that she did in college and in Italy but also her artist’s books and videos and the incredible diazotypes she made in New York, work that didn’t necessarily immediately come to mind when we thought of Francesca Woodman. So I tried to show the expansiveness of her practice, the complexity of it, and also that just before she died, it was moving in a direction quite different from where she had started.

The other thing that felt very important to me was to remember just how young she was, and to remind viewers that most of this work was done while she was a student. That’s not meant to be disparaging. Many writers have struggled to characterize her work, and the scholarship is conflicting: she’s a feminist, she’s not a feminist, she’s a surrealist, she’s not a surrealist. . . . and I think the reason we can’t quite pin her down is that she was still finding her way as an artist. She was an artist in formation, and artists in formation are exploring; they’re trying things out. So I wanted to make room to appreciate that kind of youthful play, that self-exploration, which I felt hadn’t been admitted into the picture of Woodman yet.

PTYou touched on her interest in making work serially. The SFMOMA exhibition included groups of related works and existing series, as does our Gagosian show. How do you think the serial aspect of the work informs our general understanding of what she was thinking about in her photography?

CKIn a journal, or maybe a letter, Francesca wrote about making work the way she learned to play piano, in that you start with a theme and then learn the variations on the theme. The composer begins with a simple theme and then elaborates on that theme over many variations, embellishing the melody and exploring it at different tempos and in different keys. The angel is a theme that appears over and over and in various manifestations across Francesca’s work, even arguably in her very earliest work from high school, where she posed nude in the cemetery against the gravestones. From the very beginning, she’s clearly thinking about the body, and death, and the figure of the angel. The imagery is not consistent but the ideas she’s exploring are. She tended to work out a problem over time, in different contexts, and to return to themes many times from different angles. She did do a few pictures that are sequential—they’re obviously meant to go one, two, three, four, in an order. But in general her approach to sequence is more like a tangled web of relationships than like a string of pearls on a necklace.

PTIs there a particular body of work or an image to which you return often?

CKI’d say the thesis installation, referred to as Swan Song [1978], that she did at RISD. It’s much less known than her other work, because it was an actual physical installation and had to be experienced in person. I don’t think she ever showed it again, but I often work with undergraduates and what they choose to present for their BFA thesis shows is important, right? It signifies where they see themselves at the end of a four-year education and where they’re hoping to go. Francesca took herself very seriously—far more seriously than a typical undergraduate, I’d say—so I think we have to take her final work as a student seriously, too.

The exhibition combines her interest in the body in space, the expressions of presence and ethereality, with a new experiment in scale. The prints are much larger than anything she’d printed up until that point: before those works, she never printed anything larger than 8 by 8 inches and these are more like 40 by 40 inches, maybe larger. She installed them in the architectural space of the gallery, not in frames but pinned to the wall, mostly in pairs, in a corner of the gallery, all the way up at the ceiling or down at the baseboard. And she included a mirror, so that the space of the gallery was also incorporated into the experience of seeing the work.

The installation illuminates the issues that became increasingly important to her, that you then start to see elaborated in the diazotype work she did later in New York. Because so few people saw that installation, it probably hasn’t had that much of an impact on how people have viewed her work, but to me it marks the beginning of a shift in her thinking. Even the way she took those pictures is significant: she drilled a hole in the ceiling of her studio and the camera is positioned above, looking down through it, so there’s both a kind of voyeurism and an omniscience to the point of view. It’s a sophisticated way of thinking about looking, about being seen, about the body in space, and the way space affects our encounter with artwork.

PTRight, not only does she consider space within the photographs but she also asks us to experience the space around her work within its presentation. Could you elaborate a little on how you think the space around Francesca’s body operates in her images?

There’s both a brutality and a monumentality about the bodies she depicts, and you don’t quite know whether they’re trapped or liberated.

Corey Keller

CKI would say for starters that it really demonstrates the level of ambition she had. I think that’s one of the most striking things about her as an artist. I don’t know if you remember yourself when you were twenty years old—

PTOh god, I try not to remember.

CK[Laughter] Yeah, I would really hate for anybody to spend the kind of time thinking about what I did as a twenty-year-old that people have spent thinking about what she did as a twenty-year-old, right? I think she’s imagining something for herself, a kind of place in the world. I feel like she’s thinking about taking up more space, in a sense. She shifted from intimate small-scale photographs to a practice that forces the viewer to think not only about bodies in space but about their own body in space as a viewer.

PTAt the time of the retrospective, you were one of the very few curators able to see all the work that Francesca held on to in her lifetime, and that passed on to her parents after her death, as well as a limited number of her personal archival materials. Given that Gagosian and the Woodman Family Foundation now have the ability to share more of this material for study, I wonder if you think there are new possibilities for scholarship and interpretation and how you see that changing the landscape around her work.

CKI think there’s a huge opportunity. I was just thinking, When can I write the next book? For a while, her parents, the artists George and Betty Woodman, were understandably sensitive about letting people look at Francesca’s journals, because they felt her words had been misinterpreted or exploited in the past. But with thoughtful scholarship I think there’s a great deal to be learned. For starters, Woodman wrote in her journals about exhibitions she saw. She has invitations and announcements and clippings tucked in there. It becomes really exciting to look at her work in the context of what she herself was looking at, because she was a voracious art-looker—she’d grown up going to museums with her family her entire life, and she read and looked at everything. You can’t think of her as this isolated genius who sprang into the world completely and fully formed; she’s deeply, deeply enmeshed in a larger world of art.

I would personally love to explore more deeply the web of artworks and artists Francesca was interested in. When I was working on the SFMOMA exhibition, for instance, I wanted to know if Ralph Eugene Meatyard was somebody she was looking at. Katarina [Jerinic, the Woodman Family Foundation’s collections curator] sure enough found a clipping of a quite obscure article about Meatyard in an issue of Criss-Cross Art Communications, a publication with which Francesca’s father, George Woodman, was heavily involved through the University of Colorado. She would likely have encountered it there. That’s fascinating to me because Meatyard’s work was not as widely known then as perhaps it is now. So it suggests a real awareness of what other photographers were doing, but also makes me want to look more closely at the particular artists she had an affinity for. There’s tons of research to be done on connections like that.

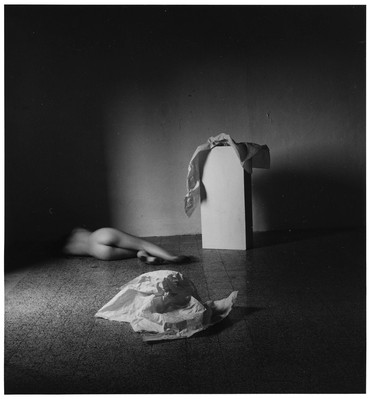

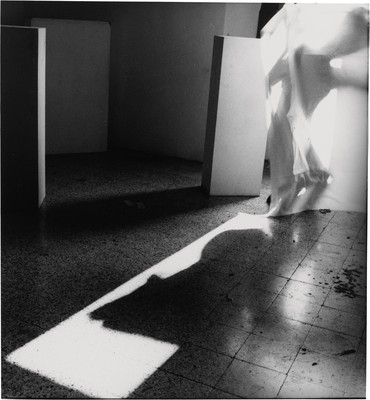

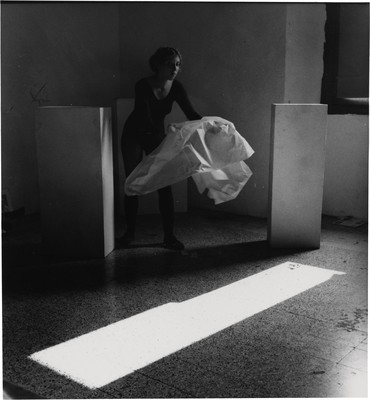

I think there are themes in the work that could be explored further. For the retrospective I organized the work chronologically, to give viewers a sense of how it developed over time. When you group the work thematically instead, you start to see connections across pictures that you might have missed otherwise. And in fact I think the selection for your show illustrates that in beautiful ways. The pedestal, for example: there are plinths in many of the works, from different groupings, that when you see them individually read like abstract shapes, but when you see the same pictures next to other works, the shapes are clearly pedestals. So now I see in one of those works not a figure lying on the floor next to a rectangular box but a figure who has fallen off a pedestal. Putting work you know in new combinations makes you view the same photographs through a totally different perspective. It’s exciting to shuffle it all up and see what new through lines emerge.

PTI love that you brought up that group of works, because for me, viewing them together for the first time was a revelation. The pedestals echo the frame of light falling on the floor. She uses light as a formal object in these images, mimicking the pedestal, an actual object.

CKI think I hadn’t fully realized until now just how important the pair of Blueprint for a Temple [1980] works are in her body of work. I think because she made them toward the end of her career, so shortly before her death, they almost don’t get digested like the rest of her work. They aren’t part of the Woodman mythology in the same way; it seems like a thing apart. And what the grouping in this show makes clear to me is that all her work was moving toward this, that the Temple was sort of a climax rather than an outlier.

PTI think that’s true. I mean, it’s remarkable that she makes these two monumental temple works in 1980 and finds an incredible delivery for all of these ideas—remarkable because of their scale, but also because the ideas are so fully formed. As you’ve said, everything in these individual images is extracted and distilled in such a profound way, literally using her body as architecture, forming a temple.

CKI love its monumentality—I mean, what could be more solid and majestic than a Greek temple? She wrote in her journals that she was tired of making small work, and here she certainly goes in a different direction. The piece evokes the epitome of classical perfection and it’s also hilarious, because all the different parts are pieces of her bathroom: bathtub claw feet, the pedestal for her sink—anyone who’s lived in a New York rental apartment recognizes that Greek key tile pattern. In a smaller diazotype mounted on the right of the larger work, she writes about the bathroom as a modern temple, this place of respite from the chaos of the world. She could be kind of a little imp. Which I think doesn’t always get appreciated about her as well. She was very funny.

PTYes, very funny. And you said this earlier: she had so much experience of the world at such a young age. I mean, her parents were artists and they traveled and she was taken to world-class museums. She was consuming the world around her. That’s rare. We were taken to places as young kids, but we weren’t always engaged—“we” meaning me, I’m speaking for myself. Woodman not only absorbed the art in the museums but she also looked at ordinary things like the bathroom tile and saw an opportunity to make art.

CKShe had a visual appetite that was just voracious. I mean, it must have been difficult to grow up with two successful artists as parents. How do you position yourself in that world? She was driven to look by professional ambition but also by a deep curiosity. I was laughing because I took my kids to the Vatican a couple of years ago and my kids, who were about nine and thirteen, declared it the most boring place in the entire world. Francesca was going to those places and she wasn’t telling her parents it was the most boring place in the world. She was probably all over it. Her parents used to send her and her brother Charlie off with sketchbooks so that they themselves could look at the art in peace. And my kids were like, “Where’s the gelato and can we get out of here?”

PTYou can’t fault them for that—gelato’s delicious. But I do think it’s remarkable how tuned in and fed Woodman was by the world around her.

THE GROUPING IN THIS SHOW MAKES CLEAR TO ME . . . THAT ALL HER WORK WAS MOVING TOWARD THIS, THAT THE TEMPLE WAS SORT OF A CLIMAX RATHER THAN AN OUTLIER.

Corey Keller

Do you think there are specific elements of her work that we need to reexamine as a contemporary audience, given the passage of time?

CKI think it’s worth reevaluating the context for her work, what was going on around her artistically. I’m particularly interested in looking at her work in relationship to the Pattern and Decoration movement, because that was in part a response to the cold, machined masculinity of Minimalism. Pattern and Decoration celebrated the feminine, craft, the handmade (which I think is also interesting in relationship to some of the stuff going on now), and it was a sensibility to which her father ascribed, as did some of the other artists she was personally close to. I think every time the machine looms large, this countercurrent springs up to meet it: an embrace of the tender and the intimate and the detail. But Pattern and Decoration never became a major mainstream movement, and it often gets downplayed as a sidenote. I think those sidenotes often give us a richer, more nuanced picture of what was going on at a particular moment.

When I was writing my essay for the exhibition catalogue, I was reminded that she was making these intimate self-portraits at the same time that the famous landscape-photography exhibition New Topographics [1975] was organized as a kind of summary of photography’s dominant mood. You couldn’t find two bodies of work more diametrically opposed. But art history tends to stick to certain narratives. If you say “1975” to a historian of photography, they reflexively respond with “New Topographics.” That’s the model we have of what’s happening in 1970s photography. But in fact it’s only a part of the picture.

You could also think about her work in relationship to Cindy Sherman’s film stills, which she started making in ’76? Nominally there’s a comparison to be drawn between two women making photographs in which their own bodies appear, but Sherman is deeply engaged with popular culture and the media machine and Woodman couldn’t care less about any of that. There’s no irony in Woodman’s work, no social commentary, no archness. She and Sherman are coming from two very different places and using the camera in entirely different ways. One of the lessons to be drawn from Woodman’s work is that a far more interesting story can be told about photography, and maybe especially photography by women, during that time.

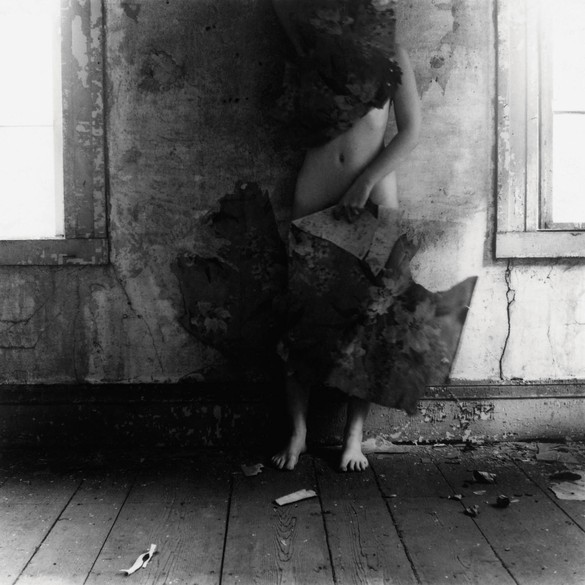

PTA motif that strikes me in Francesca’s work is the body collapsing into the environment, or into architecture—there’s a lot of classical imagery, ruins.

CKFrom the very, very beginning, even from her high school work, there’s a sense in her pictures of the body either emerging from or being consumed by architecture, it’s never entirely clear which. Is she coming out of wallpaper in that room or is the wallpaper eating her? There’s a series where she’s in her studio and she’s moving in and around this big sheet of plastic wrap—there’s a formal elegance to the shapes, but also one can’t tell whether she’s being devoured or enveloped, revealed or concealed. It’s a wonderful ambiguity.

I was also looking at the picture Space² [1976] again, with the door that’s propped at that impossible angle and a body underneath it. I had always seen it as a dreamlike picture, where the door is almost floating gently, almost magically, in space. Look again and it’s a guillotine, it’s crushing, it’s dangerous. Her pictures remind me sometimes of Greek mythology: she looks almost like a beast, like the Minotaur in the labyrinth. There’s both a brutality and a monumentality about the bodies she depicts, and you don’t quite know whether they’re trapped or liberated. That’s a remarkable achievement.

PTIn those pictures the objects bisect the space and also consume it. Counter to that, as you said, is the body. I’m never wholly convinced of the idea that she is part of the architecture when she’s holding on to a column or contorting her body to fit into the environment or to disappear into it.

CKI think what’s interesting about the work is it’s never quite only about the space and it’s never quite only about the body, but it’s about the psychological spark that ignites when those two things intersect.

In terms of form, I think her choice of the square-format camera is really important. We’re so used to seeing things in rectangles—on a screen, for example—we don’t even notice how artificial a square is. When you photograph with a square format you have four corners and you have a center, but the relationship between the center and the edges is very different in a square from in a rectangle. For other photographers—Diane Arbus, for example—their work completely transforms when they trade in their 35mm camera for a medium format. The proportions of the negative change the relationship of the subject to the frame. I feel that Woodman doubles down on that relationship of subject to space, not just in what she chooses to photograph but also in how she chooses to frame it within the square format. In the very few pictures that she made with a 35mm camera, the impact of the square format of her work becomes very evident.

PTThat’s a good point. There are visual tensions in the work she made in the square medium-format negative, and then it gets totally blown out when she starts making these caryatids and she’s free.

CKThe frame is gone.

PTIt’s gone.

CKI think that’s part of the power of Swan Song as well. The frame becomes not the photographic frame but the architectural frame. And with Temple, the frame is made of the edges of the wall on which it’s hung. It’s that kind of relationship, rather than the subject, that becomes, in all her pictures, the most important.

PTThe relationship to the viewer?

CKTo the viewer, yes, but also between the elements within the photographs. Even in the pictures that seem to be of a single subject, there’s always something else in the frame. There’s that wonderful picture, it’s the back of a chair with that beaded object, it might be a collar but she wears it around her waist in a number of her pictures. It’s draped over the back of the chair in the foreground. Nominally we could say that’s the subject of the picture, but then, in the left background, you have Woodman posed, almost like a caryatid. She’s in soft focus, and I think her head’s cut off by the frame. So what is actually the subject of that picture? It’s 100 percent the tension created by having those two elements within the frame. It’s not about that belt thing on the chair and it’s not about the figure in the background. It’s about the invisible electric lines that connect the two.

Artwork © Woodman Family Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Francesca Woodman, Gagosian, 555 West 24th Street, New York, March 13–April 27, 2024