Larry Gagosian

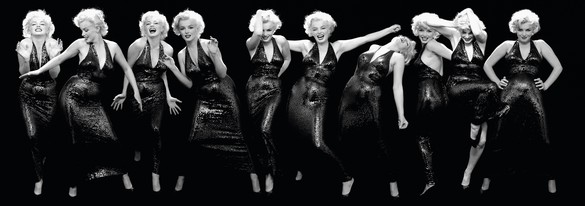

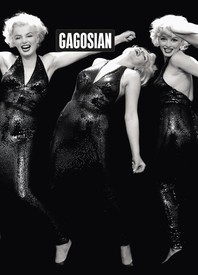

One of Richard Avedon’s most well-known portraits is of Marilyn Monroe in a moment of pensive introspection. Because she looks melancholy, and also because she would die less than five years after it was taken, it’s often referred to as “Sad Marilyn.” The world is less familiar with this mural of Marilyn, which Avedon produced using new advances in photography technology in 1994. This is what I find fascinating: it’s composed of images photographed in 1957, the same night as the iconic Sad Marilyn. Look closely and you’ll notice she’s wearing the same dress. Marilyn’s range as a performer is undeniable when you digest both images. In the mural, she is the opposite of sad: she’s a wild animal in her stride, a glamorous cascade of the ultimate female form, which has been immortalized for decades. It’s like choreographer Bob Fosse’s version of The Human Figure in Motion, Eadweard Muybridge’s 1901 book of photography that dissected human forms. For me, the most appealing part of this work is the notion that we are watching two legends at the peak of their powers: Avedon behind the camera and Marilyn in front of it. I’m a huge collector of Avedon’s portraits. In addition to the Sad Marilyn, I have acquired images of John Huston, Groucho Marx, Charlie Chaplin, Jean Renoir, and others. Avedon has a signature style and you know an Avedon when you see one. I admire his ability to keep someone in front of a camera until they exposed their true self, whether that meant waiting for them to crack and show a vulnerable side, or just cranking up the music and letting them go wild. With Marilyn, it seems he did both on the same night, which was surely one of the longest and most memorable of his career. (After all, he must have cherished the memory of that 1957 shoot to revisit it thirty-seven years later and make a new work out of it.) I met Avedon many years after he photographed Marilyn. I’d visit him in Montauk and we’d have hard-boiled eggs and champagne, which he said was his favorite breakfast. He was always upbeat, bright, and talkative. I regret never asking him about Marilyn, because I’m still fascinated by her. But I find solace in knowing that now, years after they’ve both passed, the world is still reveling in their mysterious processes, epic careers, and undeniable mark on pop culture.

Deborah Willis

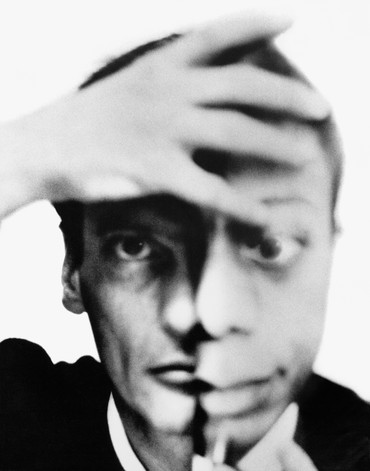

Framing a portrait of two artists who are also known as activists can be viewed as a complex production. The first time I saw the image it engaged my curiosity about masking, twinning, and storytelling. I selected this image because of the beauty of the constructed moment when I viewed it and the combination of the political and the personal merged in one single image. I have researched the philosophical writings of Baldwin and the aesthetic images of Avedon for years and find this pairing of identities an excellent example of hope, possibility, and friendship in the long rights struggle that included cultural transformations.

Spike Lee

To my dismay the great photographer Richard Avedon never took a portrait of me. It just never happened, but all was not lost. The New Yorker featured an Avedon portrait of Malcolm X with the review of my film. On my mantelpiece is that portrait of Malcolm signed to me by Avedon. I also have now on the walls of my 40 Acres and a Mule office in Brooklyn portraits of Lena Horne, Joe Louis’s right-hand fist, Marlon Brando, and Brando with Frank Sinatra. Richard Avedon was as great as the portraits he took of the greats.

Awol Erizku

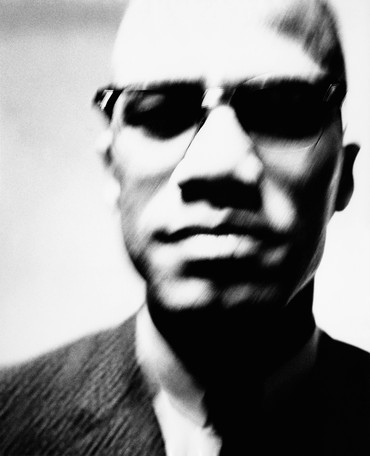

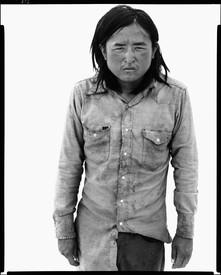

Considering the fact that this particular portrait was made in the midst of the most tumultuous and divisive decade in world and American history, marked by the civil rights movement, the Vietnam War, political assassinations, and the emerging “generation gap,” I have a strong conviction Avedon was aiming to capture the spirit of Malcolm X and not just his image. Despite Avedon’s technical and conceptual intentions with this image, I find this portrait of Malcolm X abstruse and yet inherently compelling. The departure from his conventional portraits to this expressive style is perhaps indicative that this is (in fact) a psychological portrait or an attempt to express Malcolm’s dynamic within the country at this time.

Amber Valletta

I’ve always been drawn to this image of Twiggy because Avedon’s incredibly keen eye and mastery of composition are so clearly defined in it. The symmetry of the horizontal lines in the dress, her gentle facial expression, the demeanor of her body, the twilight of the studio light: it’s all exquisite. Avedon was a master of capturing a person’s interior world at the same time he was creating a specific moment in time. Though it is a fashion picture—with a fashion credit in its title—it’s even more moving as a portrait of Twiggy, the boundary-breaking, era-defining model who launched a fashion revolution. Avedon had an entirely modern view of photography, and so much of his work has defined the history of fashion photography and continues to inform much of its future. I’m honored to have worked with him and have been moved by his work since I first encountered it. He was and remains a true legend.

Kim Kardashian

I’ve always been taken by Richard Avedon’s portrait of Elizabeth Taylor because it epitomizes her timeless beauty. In this image, he proves why she was such an icon of her era yet, at the same time, completely transcended it.

Denise Oliver-Velez

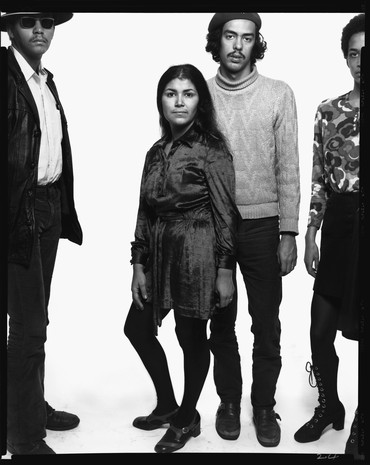

Looking at that photo reminds me of how very young we were to have the weight of leading a large group of members who were mostly younger than we were—and the amazing pressures we were faced with; we literally were Young Lords twenty-five hours a day—with a driving need to help our people while being harassed and spied on by multiple police agencies—local and federal.

Hilton Als

When I was growing up, I admired Truman Capote’s unabashed queerness. He put it out there at a time when folks thought it best to keep it in. Back then, being out could get you arrested. It took a certain amount of toughness to be who you were if you were gay and unashamed in the 1940s, also a belief in what you could project as an out gay man: an effete stylishness, and a belief in fantasy. Dick captures that in this lovely, misty, and mystical portrait of a unique American artist.

Sally Mann

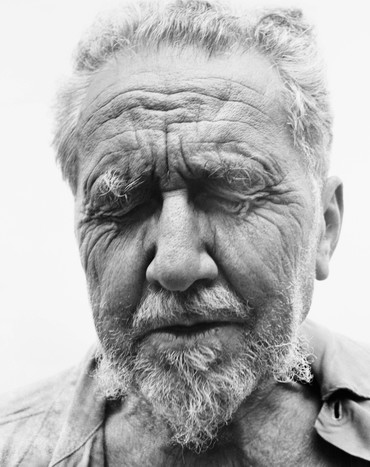

A few years ago, a picture of a man’s contorted face was used for the cover of a novel. I imagine it was chosen because of the ambiguity of the expression, although the title helpfully informs us that this was the subject’s expression at orgasm. So, unless something is terribly wrong with the guy, we can assume his face was contorted in pleasure.

The Avedon portrait of Ezra Pound is similarly ambiguous—as almost all good photographs are—although there is no mistaking what is on Pound’s face for orgasmic pleasure. At first glance it might appear to be anguish or deep grief, and that would not be an impossibility by any means. Ezra Pound was a man of oceanically deep sorrows, and he was also batshit crazy.

In 1958, the year this picture was taken, he had just been released from the bughouse, as he called it, at St. Elizabeths Hospital in Washington, DC. Shortly after this, he adopted his very public vow of total silence, which he steadfastly maintained, breaking it at long last by proclaiming, “I have never made a person happy in my life.” Interestingly, Cy Twombly told me that during this famous silence he happened to be sitting behind Pound in his private balcony at the Spoleto festival and clearly heard him speak to his wife, Olga; his voice was raspy and weak, but he was lucid. Or as lucid as a man can be who has been locked up outside like an animal in a 6-by-6-foot wire cage, keeping company with the doomed father of Emmett Till, while writing on pieces of toilet paper the uneven but often brilliant Pisan Cantos.

In this moment captured by Avedon, Pound’s expression could reflect the exquisite intensity of concentration as he declaims those very cantos to his friend William Carlos Williams, or it could be the revelatory moment before the camera when he realized he was, in his own words from “Canto 115,” “A blown husk that is finished / But the light sings eternal.”

We can never know what this wounded, bitter, and confused man was feeling, and the unknowing, the question, the gift of ambiguity is what Avedon bestows on the viewer.

Avedon 100, Gagosian, West 21st Street, New York, May 4–July 7, 2023

Artwork © The Richard Avedon Foundation