Michael Auping is an independent curator and art historian. He is well known as a curator and scholar of Abstract Expressionism, and has organized exhibitions of Arshile Gorky, Philip Guston, and Clyfford Still. He has also organized major exhibitions of Georg Baselitz, Anselm Kiefer, and Susan Rothenberg. His latest book, 40 Years: Just Talking About Art, was published by Prestel in 2018.

Alison McDonald is the Chief Creative Officer at Gagosian and has overseen marketing and publications at the gallery since 2002. During her tenure she has worked closely with Larry Gagosian to shape every aspect of the gallery’s extensive publishing program and has personally overseen more than five hundred books dedicated to the gallery’s artists. In 2020, McDonald was included in the Observer’s Arts Power 50.

Earlier this year, Michael Auping unearthed two photographs that he had saved since he was a graduate student—forty-eight years ago—documenting the preparation of a performance that Chris Burden planned for the Newport Harbor Art Museum in Southern California in 1974. The performance never happened. That said, it almost happened but was abruptly canceled because of the possibility that the museum might burn down, endangering the artist, his audience, and a number of Mark Rothko paintings on-site nearby. In this first installment of the At the Edge series, Auping gives us a glimpse into the mindset of a young, aggressive, and ambitious artist in the early stages of his career.

Alison McDonaldLet’s start by setting the scene: it’s 1974 in Southern California. What is the LA art world like at this point?

Michael AupingThere was a lot going on in the Southern California art world of the 1970s, but in my young mind there was an aesthetic holy trinity: Ed Ruscha, the father of California Pop, and in my eyes the Jasper Johns of the West; Robert Irwin, a phenomenological guru who trained our eyes to navigate the Light and Space of architecture; and Chris Burden, a young artist who wasn’t looking for light, but rather the psychological and political shadows of people and institutions.

AMcDDo you consider Chris’s early performance work a reaction to the Light and Space movement?

MAThere was an initial backlash to Light and Space, mostly from outside Southern California. The talk—generally from New Yorkers—was that creativity came from an artist’s discomfort with the world. The perception was that Southern California didn’t have this discomfort. The Light and Space movement—which I loved and still do—seemed to be, and in fact was, a pure meditation on perception. There appeared to be no discomfort, only pure seeing. Then along came Chris, who woke us all up from our meditations. You could not ignore his drama and I have no doubt that he was conscious of constituting an assault on Light and Space as a term and a phenomenon. Even then, in the moment, you had glimpses of what was happening.

Irwin taught on and off at the University of California, Irvine, when Chris was getting his masters there. It’s easy for me to see now that his grueling masters show—which consisted of Five Day Locker Piece [1971], in which he locked himself in one of the school’s small portfolio lockers for five days—was a twisted reaction to Irwin’s and James Turrell’s use of a NASA anechoic chamber to sensitize themselves to space and light. Even then, in his earliest work, you could see that Chris was transforming a widely admired movement into his own personal kind of darkness.

AMcDWhat’s your connection to this moment? Were you a student?

MAI was a graduate student in art history at Cal State Long Beach. To support myself I was working part-time at the Newport Harbor Art Museum as an installer/preparator alongside a young photographer, Brian Forrest. The two of us were assigned to assist Chris with the preparations leading up to his performance there. For a young art-history student, it was fascinating to see how Chris could upend what I thought of as a traditional hierarchy, one that put art history at the top, museums second, and artists third. Over the course of two weeks, he flipped that whole hierarchy on its head: Chris was going to be on top, art history second, and the museum third. He created a kind of chaos in the museum that I haven’t experienced since in my years as a museum curator (with the exception of working with Anselm Kiefer, but that’s another story).

AMcDHow was he able to do that? Can you walk me through the process from your point of view?

MAFrom the beginning, the negotiations between Chris and the museum were fraught with secrecy and tension that gradually built up, to a greater degree than what I now think of as a typical process. There were tensions from both sides, the artist and the museum. To understand that tension, which Chris often generated in his pieces, particularly early on, it’s important to understand the context. Chris always understood and often built his work upon the context of a situation.

By 1974, Chris was already internationally infamous. He had already made some of his most controversial works, the most well-known being Shoot [1971], in which he stoically stood at the end of a white gallery and had himself shot by a friend with a .22 caliber rifle. Among other messages, that piece announced early on that Chris would not back down from danger or controversy, even for a museum show. Newport Harbor would have been his first show or performance in a museum. The way Chris thought, he wouldn’t have felt it worthwhile to do anything benign, he had to make a strong statement. It’s hard to describe the psychological uncertainty that Chris could create in those early days among his audience, institutions, and even art-world friends. You either loved him or you hated him.

AMcDTell me about the Newport Harbor Art Museum. I know that much later, in 1997, it became the Orange County Museum of Art. But what was the institution like at that moment in the mid-1970s?

MAThe Newport Harbor Art Museum had an early history of being on top of the SoCal zeitgeist. There were two curators there at the time, Phyllis Lutjeans and Betty Turnbull. They wanted to be the first museum bold enough to do a Burden piece. These women had a lot of guts. Newport Beach is in Orange County—sailboats, yachts, palm trees, and dichondra lawns. Burden was the perfect artist to scare beachy suburbanites out of their complacency and self-satisfaction.

Phyllis was a true renegade and a classic example of how Chris could manipulate your psyche. Two years earlier she’d been at the center of Burden’s TV Hijack: during an interview she was doing with him for a local television station, Chris pulled out a large knife and held it to her throat. He threatened to cut her if the station stopped the live transmission. According to Phyllis, Chris didn’t tell her in advance that he was going to turn the interview into a confrontational performance. When it was all resolved without bloodshed, Phyllis said she didn’t think Chris would have hurt her, but she didn’t seem absolutely sure.

Phyllis understood how smart Chris was, but also how twisted. She wanted to do a show at the museum and you could argue that he owed her one. So she brazenly approached him and he said he’d think about it. As it turned out, the performance was as much about prelude as about final act.

After some cat and mouse, Chris eventually agreed. Everyone at the museum was excited . . . for a few days.

AMcDThen what happened?

MAWell, the plot thickened. The museum had just hired a new director, James Byrnes. He wasn’t an expert in contemporary art but he was well versed in Abstract Expressionism. Jim, bless his heart, wasn’t prepared for Chris Burden. Chris’s performances were like guerilla warfare. You never knew when one would happen; they weren’t advertised, you had to be invited, and the mailing list was small, his audiences were small, but intensely loyal. Usually no one except Chris knew in advance what he was going to do. There was always a sense of nervous anticipation, which he cultivated.

Not knowing the plan for Chris’s performance didn’t sit well with the new director. As the liaison between him and Chris, Phyllis was put to the task of finding out the nature of the piece the artist would do. Chris was silent on that subject during all the preparations.

Now, it’s important to mention that the museum had just closed Mark Rothko: Ten Major Works, which Jim had organized. It was a stunningly beautiful show. To bring out the light in the paintings, the walls were painted a dark maroon. The darkness of the galleries and the nuanced light that seemed to emanate from the paintings was much talked about. That show was well attended and extended due to its popularity.

I think, and a few others did as well at the time, that the Rothko show provoked and inspired Chris in various ways. Doing a performance in the wake of the Rothko adulation would be a challenge. There were still a few Rothkos in the museum’s storage room at the back end of the main gallery that hadn’t been returned to their owners. Rothko was still in the building. And Chris insisted that we keep the maroon walls that had been used for the Rothko show. To me, that was a sign that his piece would be to some extent about Rothko.

The way Chris thought, he wouldn’t have felt it worthwhile to do anything benign, he had to make a strong statement.

Michael Auping

AMcDLet’s talk about the performance itself. What were you tasked with preparing for it?

MAA week before the proposed performance, Chris had not given the museum a title or any sense of what the piece would be. He did say he’d require some assistance so Brian Forrest and I met with him. He was specific about what he needed: we had to get some bales of dry hay, a video camera with a long cord, and two monitors. A member of the museum’s board lent us a truck so we could go out to a ranch in the foothills to get the hay. There were two trips, as I recall. Chris asked us to break up the bales and spread them around the perimeter of the main gallery, which was a large, cavernous space.

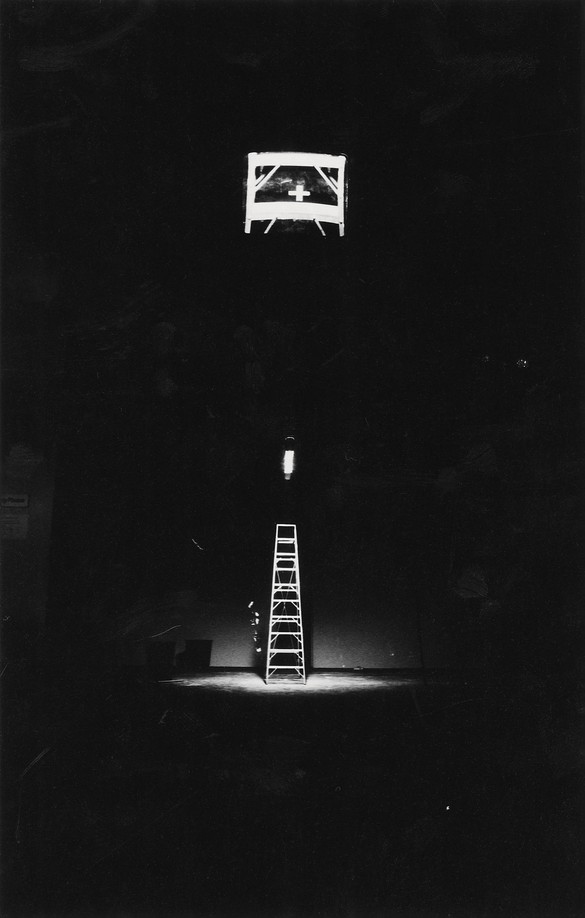

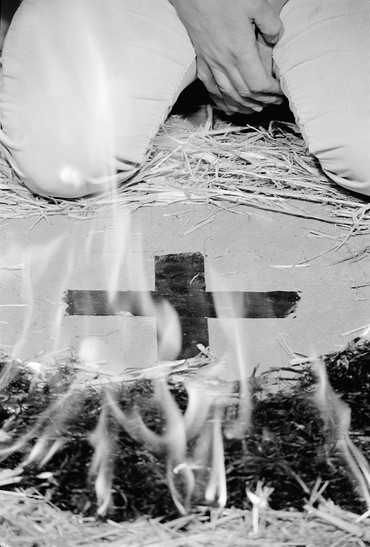

Once that was done, Chris placed two large pieces of masking tape in the center of the gallery, making a cross shape. The ladder that appears in Brian’s photos wasn’t there for the performance itself but for the setup: we hung the video camera from a high beam in the ceiling, its lens pointing down to the cross, which inhabited a relatively clean, circular area of the floor not quite encroached upon by the hay. Chris didn’t want any lights on in the cavernous gallery, except one pointed down on the cross. The hay was spread around the floor, and its brown-yellow color, surrounded by the maroon walls, gave the room a moody beauty. I thought of the hay as a Rothko on the floor.

AMcDThe stage is set and I’m starting to see connections to other, realized artworks of Burden’s. It sounds beautiful but also a bit unnerving, all that hay. What happened next?

MAChris asked me to find two sticks, fairly sturdy and each about a foot long. It sounds like a simple ask, but it actually took a while—Newport Beach doesn’t have a lot of trees, other than palm trees. I found a handful. He picked two that he liked. I asked him what they were for. He simply said “Primitive technology.” That didn’t mean anything to me at the time, but I didn’t push him to explain. Throughout the whole process I don’t think he smiled once. That’s how he always seemed in those days—he was always quite serious, which sometimes felt on the verge of alarming.

Two monitors were then mounted on the wall of a kind of anteroom just outside the gallery where the performance, whatever it was to be, would take place. The audience wasn’t to be allowed to enter the main gallery, but would watch the performance from this small room via the video monitors.

As we were spreading the hay around the gallery perimeter I tried to make small talk with Chris, some of which was revealing. I asked him if he had seen the Rothko show. He said he had. Like everyone, I mentioned the mysterious light that I saw in the paintings. Chris said, “It’s an old light. I’m trying to bring a new fire.” It took me a while to see this seemingly casual statement as connected to the artist’s fascination with fire and electricity. To my mind, some of his best pieces involved fire or electricity—Prelude to 22, or 110 [1972], Dos Equis [1972], Fire Roll [1973], Doorway to Heaven [1973].

AMcDI think I see where this is going with the cross, the interest in fire, especially when thinking about earlier works such as Dos Equis. This must have gotten someone’s attention at the museum. Ultimately, how did it get decided that after all of this preparation the performance would get canceled?

MAThe performance had been vaguely announced in the regional papers as something like “Chris Burden Performance at Newport Harbor Art Museum,” but even forty-eight hours before the performance the director still didn’t know what this preparation was about. As much as Phyllis pressed him, Chris said nothing. At that point Byrnes demanded to know, and said that he’d cancel the performance if he wasn’t told within hours. Finally, Chris matter-of-factly told Phyllis that the performance would consist of him rubbing two sticks together to create a very small fire, using a tiny pile of hay where the cross was.

AMcDOh my. Art institutions certainly don’t like to play with fire, especially not with borrowed Rothkos in the building!

MAThe new director and the curators became almost hysterical. Chris told them that he wasn’t sure whether he could even get the fire going with the two sticks I’d found, but that didn’t come close to calming them: if he were to make even one small spark in a room filled with dry hay, there was the possibility that the whole place could go up in flames. Hours were spent talking about the fact that the audience would be in another room, somewhat distanced from the performance, and that while the Rothkos were in the building, they were in a back storage area.

If things did go wrong, Chris would have been the one most in danger. Unfortunately, most of the talk centered on the safety of the Rothko paintings that were there in storage, as well as various insurance issues. At that point Chris was furious. When asked if he’d consider pretending to light a fire but not light one, he laughed. It was a John Wayne–style standoff (at the time, John Wayne was one of Newport Beach’s most famous residents). As much as Chris had put himself in peril in many of his previous performances, and his audiences in psychological dilemmas about whether they should help or intervene, he was now going head-to-head with an institution. Chris was right: Rothko had his fire and Chris had his. It was like Muhammad Ali against Sonny Liston: Ali got into Liston’s head by acting so erratically. It’s said that a strong man isn’t afraid of another strong man, and a skilled man isn’t afraid of another man’s skills, but everyone is afraid of a wild man, because you have no idea what he’ll do.

The performance was canceled. It was the day before it was meant to take place. It was already promoted, so people still showed up on the scheduled day and time. I was working in the museum’s bookshop the night the performance should have taken place and there was a crowd lined up around the block. There were a lot of pissed-off fans. It was a moment when Ruscha’s famous Los Angeles County Museum on Fire [1965–68] almost became literalized in Orange County. Knowing Chris, he could have been referencing that as much as the Rothkos.

AMcDWhat made you think about this unrealized performance again after so many years? Why did you hold on to these photos for so long?

MABrian gave me two photos he had taken of our installation because I’d intended to write an article about my experience at some point. In the end there was no essay, and decades later, when Brian’s archive of photographs went digital, the negatives were lost. Somehow I kept my prints in a file for forty-eight years! They capture those dark, Burden-esque moments in Southern California art history. I like the gritty darkness of them, depicting an empty stage, as it were. The audience and the actor have to be imagined. The audience and the actor have all gone home.

AMcDDo you think of Chris as an actor?

MAYes, in those days I did. He was an actor in the best sense because he could make you feel in yourself the complexities of fear, or something like fear. Later in life, when Chris began working more specifically as a sculptor, he stopped being an actor. I appreciated that period of his being an actor and performer. As others have said, Chris played a Jesus-like character, on the edge of some type of a darkly spiritual breakthrough.

The cross on the floor of the Newport Harbor Art Museum was a prelude—a word Chris liked to use—in which one act was building toward the next. Months later he would literally nail himself to the back of a Volkswagen Beetle, creating a self-crucifixion.

AMcDWould you say that there was a general consensus about Chris’s work at that time?

MAThere were two ways of reacting to his work back then: hate it as a form of masochism or romanticize it as a form of spiritual energy. He used his performances to channel deeply hidden energies. The Church of Human Energy, which was a great text-based print that he made in 1973–74, helped me see his art in a new way. I always wanted to buy that print. By the time I could afford it, they were sold out.

If he was nothing else, Chris was a romantic, and a philosophically smart one. A fair amount has been written about Western art history being a metaphorical struggle between the dark and the light. One could imagine the ’70s in Southern California as mimicking that struggle, the Light and Space movement representing a new enlightenment and Chris Burden depicting what the romantic poet Novalis called an urge toward “the holy, unspeakable, mysterious night.” Now clearly I’m romanticizing, but the bottom line is that I think I kept those photos because I treasure that moment in Southern California art.

AMcDWhy do you think that there’s no mention of this unrealized performance in the artist’s archive?

MAIt’s fascinating that there are no notes or drawings anywhere for this piece. I talked to Chris about it only once afterwards. I asked him what he thought about the outcome. He thanked me for the help on the preinstallation and said it was a partial success. He indicated that he wouldn’t have burned down the Rothkos or harmed any of the people who came, but said that he had to do what he had to do.

AMcDLooking back on this now, do you see any influence this piece may have had on subsequent works?

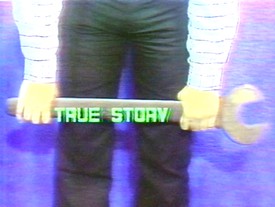

MAIn my mind, this unrealized piece set the stage for a number of subsequent works. A few that come to mind are Transfixed [1974], with its religious overtones, and Do You Believe in Television? [1976], which involved the spreading of hay in a concrete stairway. The hay was set on fire, and spectators were allowed to watch the fire from different levels of the stairwell. In that case Chris used matches rather than sticks, though. The title notwithstanding, he knew that the question wasn’t whether we believed in television but what we believed of Chris Burden and his motives. That was always the question in those days.

Artwork © 2022 Chris Burden/Licensed by the Chris Burden Estate and Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York