Lisane BasquiatBetween 1982 and 1984, Jean-Michel Basquiat enjoyed frequent trips to Los Angeles, staying for months at a time. He loved to work and live in LA. He made lots of friends and appreciated the respite from New York and the opportunity to really focus on his art here. Between 1982 and 1986, he had three solo exhibitions at the Larry Gagosian Gallery. He maintained a studio space in Venice that Fred Hoffman found for him and created a suite of prints with Hoffman. Tamra Davis was a film student at the Los Angeles City College and a gallery assistant who drove Jean-Michel around LA. We were all very close with Jean-Michel—we knew him as friends and family. That’s part of why Jeanine and I were excited for the opportunity to talk about him and share stories. We are just as excited to hear some of these stories as you are.

Jeanine HeriveauxLet’s start with you, Larry, since you met Jean-Michel first, I believe. You were the first person to invite him to Los Angeles, and he went out there in 1982 to live with you and work on paintings. How did you first meet?

Larry GagosianI met him in 1981, if my memory serves me, at Annina Nosei’s gallery in SoHo. It’s kind of an interesting story because a friend of mine, Barbara Kruger, was in a group show at Annina’s and called me up. I had a loft on West Broadway a few blocks from Annina’s gallery. And she said, Larry, what are you doing? I said, I’m not doing anything. She said, Well, why don’t you come over?

So I walked over to Prince Street to Annina’s gallery, and there were, as I recall, three exhibition rooms in the gallery. When I walked into the third room, which was the last room in the gallery, I saw five or six paintings and—they just stopped me cold in my tracks. I mean, my hair stood on end. I was just transfixed by these paintings and how powerful and original they were.

Annina walked over to greet me—her office was just behind that final room where Basquiat’s paintings were hanging. And she said, Larry, do you like these? And I said, Like them? I mean, they’re insanely powerful and brilliant. Are any of them available? [Laughs] And she said, These three I haven’t sold yet. I said, Well, how much are they? And I think she said they were $3,500 each. So I bought all three of them. Sadly, I no longer own these paintings, which is a somewhat painful topic. [Laughter]

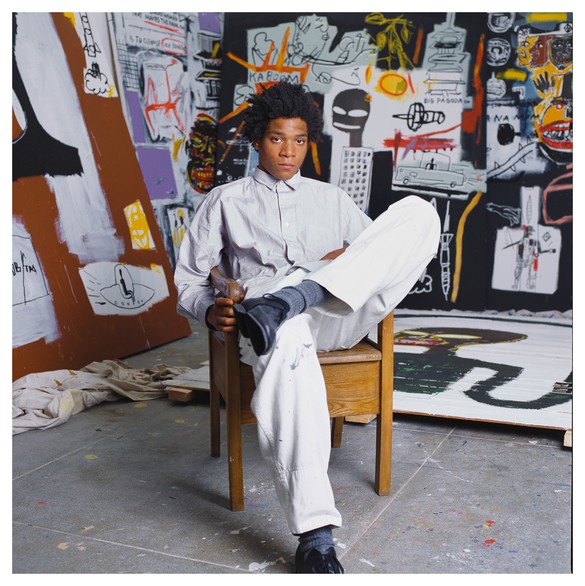

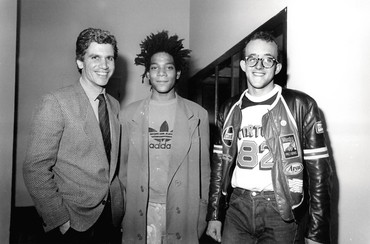

And then she asked if I would like to meet the artist and I said, Yeah, sure. So she walked me into her office. I had no idea who Jean-Michel Basquiat was at that time. I’d never seen a reproduction of his work, I’d never heard his name. I had zero awareness, as virgin as you could be in that situation. And there’s Jean-Michel with his trademark hair sitting there smoking a joint, and he had on white painter’s overalls that were covered in paint. And I asked him if I could, you know, smoke a little with him. Apparently, that was the right way to start the conversation. [Laughter]

JHWhat was your first impression of him?

LGThat he was extremely intelligent. I could see that immediately, just the way he handled himself. He was young—twenty or twenty-one years old—but poised.

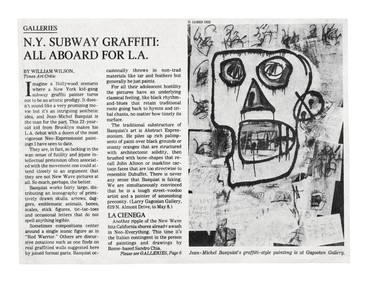

A couple of days later, Annina and Jean-Michel invited me to his studio, which was in a space beneath her gallery. And it was full of paintings. They were all unbelievable, so I pitched him the idea of doing a show in my gallery in LA, in West Hollywood, and he was totally up for it. And Annina was very gracious about it. She gave it the green light, and that’s how he ended up coming to LA.

FRED HOFFMANAnd that was one of Jean-Michel’s first gallery exhibitions. Larry opened that solo show of his work in LA in April of 1982. Almost simultaneously, Annina opened an exhibition in New York in March of 1982, which was his first official solo presentation in the United States.

JHFred, what is your first recollection?

FHI did not meet Jean-Michel when he came to do that first show on North Almont Drive, Larry’s original West Hollywood gallery, but I saw it two or three times and was blown away by it. Larry called me a little later in the year, in November of 1982. I was living in Venice and had just started a print publishing business called New City Editions. I was doing prints with some local artists and had also started working with Frank Gehry on what became known as the Fish Lamps. And Larry said that he was there with Jean-Michel, whom he had invited back to LA. The plan was that Jean-Michel would both work and reside at Larry’s new house on Market Street in Venice. Jean-Michel had moved into the ground floor—it was completely separate from Larry’s residence above. It was actually built as an art gallery and had separate living quarters. Anyway, Larry asked if I’d like to meet with Jean-Michel to talk about making a silkscreen print, an edition. I said, Absolutely.

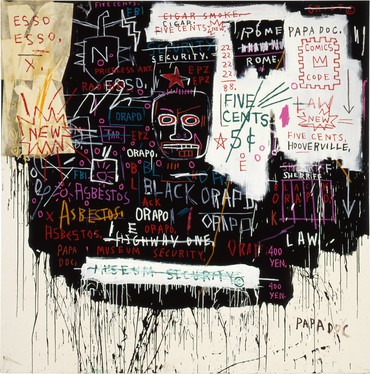

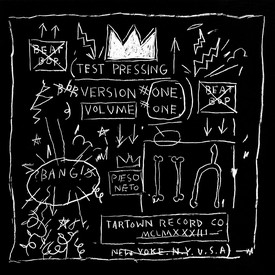

I came over, I think the next night after dinner, and Jean-Michel and Larry and I started talking. Jean-Michel presented to me an idea that we started working on right away. It was called Tuxedo [1983], a very important, large, ambitious silkscreen work. The completed work is 8 ½ feet tall by 5 feet wide, and it took months to make. Jean-Michel and I connected right from the beginning, and I had a clear sense of how to bring it along, who to bring in. We had ten different assistants working on it at different phases.

LGJust to add one little footnote, I named Tuxedo. It’s a black-and-white piece—there is writing and drawing with a white crown on the top. And when I saw it, I said, You’ve got to call that “Tuxedo.” And Jean-Michel wasn’t the easiest guy to convince about anything. [Laughter] I’m very proud that I named that piece. And Fred of course realized it and made it into a very significant work.

LBTamra, how did you meet Jean-Michel?

Tamra DavisWe met when he was coming to do the show at Larry’s gallery. I was good friends with Matt Dike, who worked for Larry at the time. I was going to film school, and my day job was working at another gallery down the street.

Matt and I were kind of assigned to help Jean-Michel with anything he needed while he was in LA. He didn’t really know anybody, and we knew what was fun to do, so Larry asked us to drive him places, take care of him, and bring him to clubs. I got assigned to pick him up at the airport, but I had no idea what he looked like. And I see this guy—he’s so gorgeous, but like no one you’ve ever seen before, and I was like, Oh my God, I think that’s him. And I don’t think he had any luggage, or if he did, it was just a carry-on.

LBHe probably didn’t.

TDI remember coming back over to the studio and—was Matt living there? There was a little house in West Hollywood—

LGHe was driving because I’d lost my license—

TDRemember that little house on that back street?

LGOn Nemo, that house, yeah.

TDI brought him over to that little house on Nemo. He made a big splash when he first came to town, for sure.

LBI’d love to hear more from each of you about what your relationship was like with Jean-Michel. Jean-Michel was always very clear about what he wanted, what he didn’t want. But what were your interactions like?

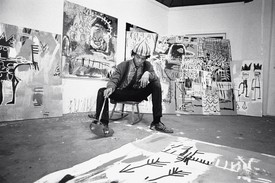

LGHe was making paintings and living in my house. He had his own living area and he painted downstairs in the studio, which turned out to be an ideal place for him to work. And I was selling his paintings and we were also becoming friends—we were hanging out a lot, going out a lot, having a lot of fun. It was kind of a golden moment.

JHTell us about that.

LGWe’d go shopping. We’d go to restaurants. We’d drive around town. I don’t remember everything, but I remember that it was very enjoyable and that I had an absolute genius working in my house, so I got access to his work, and we became genuinely good friends. I really loved the guy. He was a hard worker, but when he wanted to have a good time—

LBWork hard, play hard.

LGHe knew how to do it.

FHJust adding to what Larry said, as it got late at night, Larry and I probably backed off and went home. But Jean-Michel would basically just be getting started, hanging out with the people of his generation in the clubs. I don’t know when he slept. He was basically working from the middle of the day into the night and then out every night.

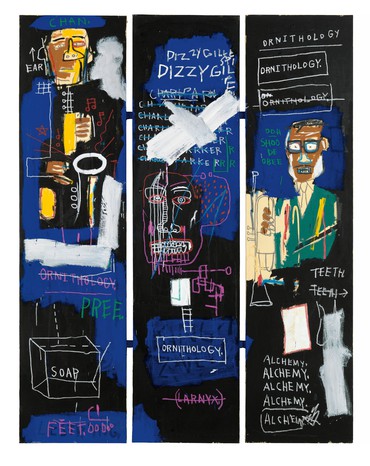

My relationship was, in a way, two professional relationships. I have a PhD in the history of art, so we shared a lot about art history. For instance, I had very engaging conversations with Jean-Michel about Leonardo da Vinci. I had an extensive library of books on da Vinci, which I would bring over to the studio, and we’d riffle through them. I would bring over other art history books as well, and he could go through a book in twenty minutes.

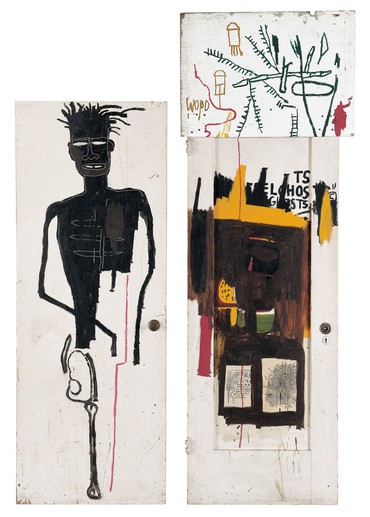

And then I had a professional relationship with Jean-Michel as the producer of what turned out to be, except for one print that Annina made with him, the only editioned works he made during his short lifetime. We produced six editions. Beyond Tuxedo, we made another very ambitious piece called Untitled [1983]. We made Back of the Neck [1983]. We made this five-panel work, Untitled (from Leonardo) [1983], and two single prints [both 1983] with Leonardo-derived images.

Beyond that, after this first engagement in Venice at Larry’s house, Jean-Michel decided he wanted to come back to LA and have his own studio, which I found for him. It was only three doors down from Larry’s house, also on Market Street. Jean-Michel worked there, but he lived at the L’Ermitage hotel in West Hollywood. His second foray in LA started in the fall of 1983 and went through June of 1984, during which time we worked together on a series of silkscreen prints. For those, he used images derived from original drawings that were turned into silkscreens and then screened onto canvases. I also helped him on a famous series of paintings, large works that were quite unusual because they were painted on wood slat fencing material. There was a fence on the backside of Jean-Michel’s studio. One night he went out into this little back courtyard and tripped over a homeless person who had wedged themself between two slats. It completely freaked him out, so when I came in the next day I said, Well, there are a few options. We can rebuild it, or we can take down the wood fencing material and you just don’t go out into the courtyard. You don’t need to go out onto Speedway Avenue at two in the morning. Maybe just play it safe.

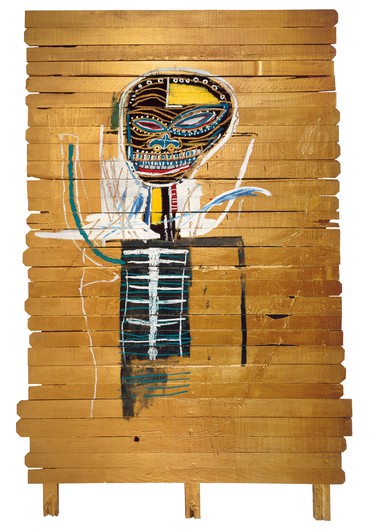

He said, Yeah, we’ll go for that. So we started taking down the fencing material, and I went to get a dumpster so we could throw the slats away. But he said, No, no, bring it all inside, so we started carrying all of these wooden slats into the studio and stacking them up. I left. The next day I came back and he’s got a crew of people assembling these slats into picture supports. One turned out to be a great piece, in the Broad Collection, called Gold Griot [1984]—one of the greatest works in Jean-Michel’s oeuvre. And there was another great work, the companion piece, Flexible [1984], which he kept for himself.

LBTamra, you all were clearly having fun. What was going on?

TDI loved hanging out with Jean-Michel. Matt Dike and I were best friends, and Matt kind of ran the LA music scene. If you wanted to go to clubs in LA, you wanted to hang out with Matt Dike. And my favorite memories are of Jean-Michel and Matt playing records together. At the time, Matt was just about to start his label, Delicious Vinyl. Jean-Michel would be in his studio above Santa Monica Boulevard all the time, and Tone Loc would be there, and I was making music videos in those early days and made “Wild Thing” for Tone Loc and “Bust a Move” for Young MC. Those guys were coming in and out of the studio and it was really fun to see Jean-Michel interacting with the LA music and rap scene. There was this New York/LA hip-hop scene, and Jean-Michel really loved being close to that. He identified with that; it felt really familiar for him.

Whenever he came to LA, we would spend time in the clubs and talk about what was going on in the LA music scene. I was really involved in the film world, because I was going to film school and I wanted to see all these cool old movies, so we would constantly go see films. If Jean-Michel wasn’t an artist, he would have been a filmmaker.

LBWe think the same.

TDHe was always wanting to talk to me about filmmaking and films. In a way, I may have represented that aspect of his life, at least whenever he came to LA, which was exciting. And as you said, he really engaged. When you met him, he wasn’t just hanging out; he drilled you with questions and he wanted to go deeper and know things.

But there were also times hanging out with him when it felt like something crazy could happen. There was always a risk or an element of danger and excitement, like anything could happen at any moment.

LBThat might be a New York thing.

TDIs it? I don’t know, I’d just be like, Oh my God, we’re going to get in trouble. So that was kind of fun.

JHHow did you go about interviewing and filming him?

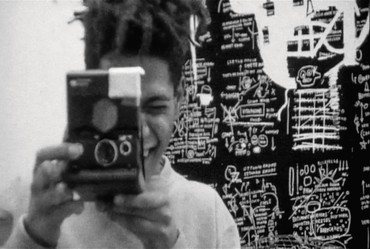

TDWell, I had a camera in my hand all the time. I’d carry a Super 8 or a Bolex. And he said that I should make a documentary about him because he was going to be a really big, famous artist [laughs].

We joked about it, but he was also really serious. A lot of times he would call to say he was in town, we’ve got to do some filming. And I would say, Sure —I never knew what it would turn into. He always felt confident that we were doing something important, like we were really making a film together.

FHWhat about the interviewing part?

TDWe actually did the interviewing later. We filmed a lot of stuff before that. He just wanted to go out and film all the time. Sometimes we would just go out and film for an afternoon, like we’d go to the racetrack or a flea market and film. But the documentary part came later, when he was at the hotel.

JHWas that the L’Ermitage—

TDYeah. We had filmed and filmed and we were getting more serious because he was actually getting famous and he wanted to document it. It was really important to him. That’s when Becky [Johnson], who was another one of my best friends and his friend, came and did it.

FHI think Jean-Michel had already had a couple of interview experiences that didn’t go so well, and he felt so comfortable with Tammy and Becky—it was so fluid and really the best documentation of Jean-Michel on camera.

LBFor sure. In curating the King Pleasure exhibition, one thing Jeanine and I wanted was to give people insight into the man behind the work. For us, it was an opportunity to really round out and share more about who Jean-Michel actually was as a person, because we think that adds to the work and it’s what audiences seem most interested in.

Larry, you made some important introductions for Jean-Michel while he was in LA, including to collectors such as the Broads. Would you talk about the clients that you introduced to Jean-Michel or to his work?

LGWell, the parties I got invited to were not necessarily the parties Jean-Michel wanted to attend. [Laughter]

LBTell us more about that.

LGI would push him sometimes. I’d say, Come on, you can do it. It’s a Beverly Hills crowd, you know? I remember one time Marcia Weisman was having a birthday party for her brother, Norton Simon, at her home on Angelo, and I said, Let’s go. He said, I don’t want to go. It’s going to be boring. And I said, Well, if it is, then we can leave. So we went and—

LBThat’s the part of the story we want to hear [laughs].

LGOf course, Jean-Michel walked in smoking a joint, which made quite an impression on Marcia Weisman and that crowd. He ultimately ended up in one of the bedrooms with some gal from the party. So he was able to adapt very quickly. He had more fun at that party than I did, let me put it that way. [Laughter]

And another great story: He was living in the house with me, he’s making paintings, we’re really getting to know each other and getting into a fair amount of trouble every now and then. He said, My girlfriend’s going to move in. And I’m hesitating, you know; sometimes too many eggs can spoil an omelet. But he insisted that she was somebody he really cared about. So I said, Okay, what’s her name? And he said, Her name is Madonna. I said, What kind of a fucking name is Madonna? [Laughter]

I really didn’t know who she was. And I’ll tell you how prescient and attuned to culture he was. He said, She’s going to be the biggest pop star in the world. And he was right. She moved in and was quite easy to be with, so we had a lot of fun and it turned out not to be a bummer. She was a good sport. She lived there for a couple of months.

FHOne story should probably be told. Larry called me one day and said, Can you take Jean-Michel and Madonna to the commissary at Twentieth Century Fox for lunch? Larry, probably through [producer] Doug Cramer, had arranged for the three of us to go, and we sat at this raised area that was sort of overlooking where the general population would eat. It was like a separate box. I sat behind the two of them; they were in the front. And Madonna looked out over this audience of probably five hundred people and pointed her finger and said, Someday everybody in this room is going to know who I am. Jean-Michel, all he could do was blush.

LBThe importance of being clear about what you want and stating it.

JHTamra, we spoke a bit about how you drove him around a lot. Do you have any stories about that, or about just hanging out with him?

TDIt was a great time in LA, and I feel like that time hasn’t really been documented so well. There was a fun music and club scene, and people were all getting along really well. One of my favorite things was to just go out dancing with Jean-Michel; he was one of the best dancers ever. Everywhere you went with him, it was like you were the center of attention. He would create a scene everywhere you went. Sometimes it wasn’t a good scene. Sometimes we realized that people were staring at us. They thought we didn’t have money or we didn’t belong there. I think he liked to shock people as well. He liked to see what kind of an impression he was going to make on people to see who they were.

JHFred, can you share a little bit more about your relationship with him?

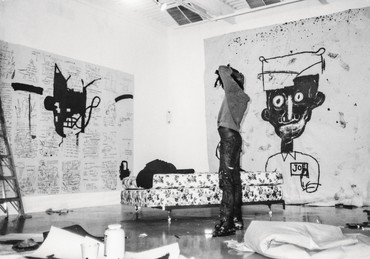

FHWe shared a lot and he had such a great understanding of the history of art. He understood exactly how he saw himself in the lineage of great artists. When he was in his second studio, working on some silkscreen paintings, he would basically take a silkscreen, apply it to a painting, and then paint over it. There was a group of guys who would be holding these different screens. Ultimately, he made like forty different paintings, but he was working on several at once. And as he started working, it became clear that he had a deep understanding of the practice of the great masters, and especially a strong understanding about the work of someone like Robert Rauschenberg. I was very close to [noted Los Angeles collectors and philanthropists] the Grinsteins, so one day I called up Stanley [a founder of Gemini G.E.L.] and asked if Bob Rauschenberg was in town working with them. He said yes. So I asked if I could bring over a young artist named Jean-Michel Basquiat to meet Rauschenberg? And he said sure. So after dinner one night, I picked up Jean-Michel and took him to Gemini G.E.L. on Melrose. I basically introduced him to Bob and left. They spent an hour in the print shop area together and had a complete connection. Jean-Michel went back a couple of times after that, once with me and also on his own.

I think we really understood each other—I provided certain skills that he could use to push his work further. For example, it was clear right from the time I first met him that collaging unique drawings onto his canvases and painting over them was not really a sustainable method of operation. Over a lifetime, you just couldn’t make enough drawings to keep up, and also the drawings obviously have value themselves. So he started making photocopies of original drawings and collaging those into paintings. And then it became clear to him, after we made Tuxedo, that he could use silkscreen and not need to do so much photocopying. Photocopies weren’t the most sustainable medium to use anyway. So we started integrating silkscreened images into the paintings. I understood where he wanted to go, and I could help get him there quickly.

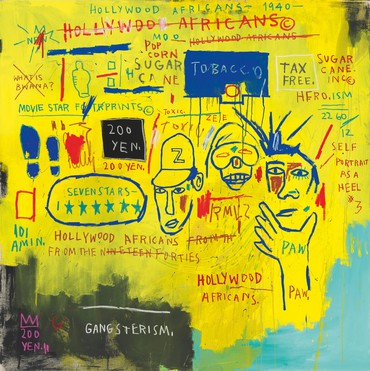

LBI think Jean-Michel Basquiat is one of the greatest painters of all time. He was a painter, he was a poet, he loved film, he loved music. He established himself firmly within popular culture. Emerging artists still look to him for inspiration. My question to each of you is, What do you think it was about Jean-Michel that makes him the phenomenon he is today?

LGDo you mind if I try to answer that? Well, he was just a genius. He had more raw talent than any artist I’ve ever encountered, or, for that matter, that anybody’s encountered. He was just a natural. I remember talking to him about a painting. He said, People ask me why do I put the blue here or the green here? And he said, I just know. He had an incredible instinct and an amazing energy. And everything just came together. He was something of a miracle, in a certain way—he had the ability to draw, he understood scale, he spent a lot of time looking at books on works by other artists, such as da Vinci, but also someone like Cy Twombly, who he also studied rather closely. But above all, he just had something that doesn’t come along but once in a lifetime—it’s hard to qualify what that is. And he knew he was good—and he just loved making art.

LBIn all forms.

LGHe’d make something and then say, Wow, this doesn’t suck, I’ll make another. In a sadly short life, he made a lot of great work.

JHAnd he didn’t only come here to work and create exhibitions with you. He came back and forth all the time. What do you think was the appeal of LA?

LGChange of scenery, friends he’d made, the climate. Getting out of New York is not such a bad idea every now and then.

FHBy the time he came here to produce the second show for Larry, he was already conflicted about how he was being received in New York. There were certain people in the New York art world who just weren’t willing to engage Jean-Michel’s work and I think that hurt him a lot. He became even more introspective, and LA provided a relief valve where he didn’t have to be under that intense pressure of making it in New York. He could just come out here and enjoy himself and get a lot of work done. It’s impressive to consider just how much work Jean-Michel produced in LA—at least a hundred canvases over eighteen months.

So LA provided a counterpoint to New York. He had a couple of periods where he was here for two or three months, but he went back and forth to New York a lot. And then eventually he discovered Hawaii, which was an even greater relief valve.

LGI rented a house in Kapalua, and it was basically two houses—I had one house and Jean-Michel had the other. I was only there for about a month. He went back several times and produced a handful of paintings. He didn’t really work that much there. He just enjoyed being in Hawaii. And it was also a way to get him away from drugs, to mellow him out—the Hawaiian vibe suited him. We had a lot of fun in Hawaii. You’re right, Fred, it was another distance from New York.

And let’s not overlook the fact that there was a fair amount of racism—

LBThank you for going there. Let’s talk about some of those challenges in New York. A lot of artists today are dealing with some of the same issues.

LGWell, now, thank God, we’re at a time where many of those railings have been identified and hopefully will start being removed and—

FHMost, but not all.

LGWell, no, there is a lot of work that still needs to be done, and serious recognition of Black artists is way overdue. Jean-Michel was really kind of a pioneer in that. He didn’t want to be a pioneer, but it turned out that that was a role that he took on. But I can describe instances of very pointed racism that would be shocking if you heard them today. I’ll give you one example, because examples are more interesting than generalities.

There was a pretty good artist who I’m not going to name, who had a good career with a big gallery. He had gone to a dinner party at a very important collector’s house, which I was dying to go to because I heard they had some really good art and I’d never been invited. I asked him, What’s the collection like? What do they have? He said, They have a lot of great things, but they fucked it up because they’ve got a Basquiat. And he was dead serious.

Another one: there was a restaurant everyone in the art world used to go to, downtown on Fifth Avenue. I had dinner one night with two very talented artists. And it was a bit of a strange conversation. They said, Larry, you seem to know the art market pretty well. You seem to know what you’re doing. We’d like to invest in art. They were asking me what they should buy, and I said, You can’t do any better than owning a Basquiat. And they said, Come on, no, seriously. So, there was always a subcurrent like that.

LBThey regret that today.

FHNot to mention the critics and the museums.

LGThe Whitney [Museum of American Art] included Jean-Michel in the 1983 Biennial, but other institutions in New York would actually not even accept gifts of his work. I tried to give a painting, a major painting, as a gift to an important New York museum, and they wouldn’t even accept it—it seems unbelievable now, but it’s a true story.

JHWell, they regret that decision today.

TDJean-Michel was so ahead of his time. When he came out, it was at a time when it almost seemed like there was a crack opening in culture for him to emerge. In the club scenes everyone mixed openly together. We were all dancing together, we were all hanging out. But then you’d get on the street and it wasn’t like that at all. That was so frustrating and I felt it too, being a woman who was trying to be a filmmaker. The walls seemed so high for us. It was like there was no way I could succeed in being a female director, there was no way he was going to be a successful Black artist. But in the club culture starting to break through, anything was possible. We could feel that shift and that kind of hopefulness in what was happening with hip-hop music becoming popular. We were all starting to emerge. It felt like it was the natural next step. But he would get so sad when people weren’t ready for him yet—

LGWell, the Broads were ready.

TDSome people were definitely ready. Thank God people saw it.

LGI remember taking Jean-Michel over to Eli and Edye [Broad]’s—they were cool with Jean-Michel; I think they were kind of amused and fascinated by him. They had a good rapport. And they were among the earliest collectors of Jean-Michel’s art, which is a great compliment to Eli and Edye.

LBAbsolutely. It blows us away how people have supported Jean-Michel and ensured that others could see the work and witness the legacy of this incredible artist. It means a lot to us.

Do each of you have any advice for emerging artists or people who are creators, whatever the art is—

FHNetwork with other like-minded souls.

LGActually, I’m asked that question all the time. Just get to know other artists and see if they dig what you’re doing. That’s probably the best path. That’s often how I hear about artists—it’s usually from other artists, so you’ve got to get into a community of artists. And of course, you’ve got to be talented.

LBThat helps.

LGYou can’t just do it with strategy. Right now it’s a very interesting time to be an artist. Still, careerism can creep in, and that cuts both ways. Why shouldn’t artists make a good living? But exceptional talent is something else, and that doesn’t come along every day.

LBI love that advice. A lot of times people go to others who are very successful and want those folks to help them, which is wonderful. But when you network with other people who have overlapping interests, that’s how you get to hone your craft and learn more about what’s happening out there, versus everyone going to a few people expecting them to help out.

TDI would just add that you have to put in the work—that’s what Jean-Michel did.

He wasn’t just saying, I’m going to be the greatest artist, or, People are going to help me out—he worked day and night.

He made it so. And that’s true for my career as well. I was filming constantly, making films, showing them. If you’re going to do it, you hope that you get discovered one day and networking is very helpful, but it’s not going to happen just because you made one or two great paintings or one film. You have to just keep doing the work, keep putting things out there.

JHIs there anything else about his time in Venice Beach and that era that you can speak about?

LGHe was very self-reliant and he knew how to figure things out on his own. I never saw anybody get the best of him. If you tried to outwit him, you paid a price. And he could have a wicked sense of humor. Henry Geldzahler interviewed Jean-Michel for Interview magazine. It was a good interview and Jean-Michel took it seriously. The last question that Geldzahler asked was, Your art deals with a lot of the struggles that you’ve gone through and your heritage. There’s some anger that runs through a lot of your art, but there’s also humor. And Basquiat had the best answer. He said, Well, you know, sometimes people laugh when you fall on your ass. [Laughter]

LBExactly. Simple.

LGThat was how quick he was.

LBHe was turned on. He was awake.

LGHe was a genius.

All artwork © The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York

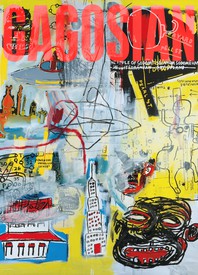

Jean-Michel Basquiat: Made on Market Street | Curated by Fred Hoffman and Larry Gagosian, Gagosian, Beverly Hills, March 7–June 1, 2o24