Francine Prose’s most recent novel is The Vixen (2022). Other books include Caravaggio: Painter of Miracles, Peggy Guggenheim: The Shock of the Modern, Reading Like a Writer, and Lovers at the Chameleon Club, Paris 1932. The recipient of numerous grants and awards, she writes frequently about art. She is a distinguished writer in residence at Bard College.

Until I showed my grandson the paintings of Arcimboldo, what he’d liked about the Louvre was skating the polished floors. But he stopped in front of the Arcimboldos, transfixed, watching the vegetables turn into a man’s face and the face turn back into vegetables.

I can visualize the vintage print in which two women merge to form a skull, the Death and the Maiden meld that has haunted Cecily Brown’s paintings. Above my desk, Ganesh, the elephant-headed Hindu god, appears in a lenticular image that changes when you move. Lean to the right, it’s Lord Ganesh, stately and regal, presiding over a table of offerings; lean to the left and the god is in close-up, chubby and sweet, the tributes replaced by candelabras. It’s a kind of magic, and we react like children when the hat produces a rabbit, when the portrait subject’s forehead morphs into a cabbage.

These optical illusions remind us—somewhat unsubtly, I guess—of how differently things look when we view them from different angles. That thought—not exactly revelatory, but all too easily forgotten—occurred to us, in new and surprising ways, throughout Timelapse, Sarah Sze’s 2023 show at New York’s Guggenheim Museum. Sze’s work tells us to look. Wait a minute. Move a little. Stop. Now look again.

Timelapse took on questions of perspective (not in the art-historical sense, but as in “point of view”) in a more philosophical way. Shine a flickering beam on that bonsai tree and it’s another plant altogether. These pieces gave us one of the things we most want from art: an invitation, a good reason, an insistence that we pay attention. Sze’s pendulums ticked off time, in case we’d forgotten how rapidly everything is changing even as we made our way down the Guggenheim’s vertiginous ramp.

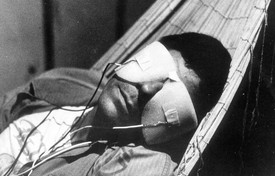

Projected images appeared on one wall, then another. It took only a few heartbeats for something we saw to become a memory. The recurring video of the bird in flight became a kind of friend: we’d seen that bird before! A construction made largely of gossamer blue threads, The Night Sky Is Dark despite the Vast Number of Stars in the Universe suggests a hammock on which ghosts could lounge should their energy falter during the Day of the Dead. Like so many of the pieces in the show, it draws our attention to the fact that everything and everyone is perpetually walking the high wire strung between the opposite towers of fragility and endurance.

Flashes of beauty appeared and vanished: there was that bird again! A hand drew a line, a volcano erupted, the sun peeked at us from behind a cloud. There was hardly enough time to think, How beautiful is that ingeniously controlled cascade of playing cards that the hand is about to deal.

Something about Timelapse brought me back to the first time I picked up a snow globe and a grown-up said: Shake it. Watch.

I must have found it shocking. Even now, it’s startling: a delicate underwater landscape explodes into sudden motion, a storm comes up, but it’s not a storm, the world glitters, the glitter subsides. It’s over in a few moments. Shake the bubble and start again. There’s no single word to describe the feelings these miniblizzards inspire: wonder, giddiness, surprise, mixed with recognition and admiration for how fragile and how durable that tiny landscape is. How mysteriously this miniature, artificial world resembles the larger world, the so-called real world, the world in which we live.

Timelapse took us back to that moment of wonder when we first saw a whole landscape transformed inside an object we could hold in one hand. Among the video images that Sze projected on the wall was a jittering pane of black-and-white static. It’s the last thing we want to see on our laptop or TV screen, a warning that’s something’s wrong, something’s gone blank. Yet here these quaking particles of electronic chaos evoked the silvery sheen of those fleeting, magical, snow globe tempests.

At once amusing and deeply serious, pleasurable and challenging, Timelapse—installed on the uppermost level of the museum’s spiral, extending down into the rotunda and out to the exterior of the building, on which video images are projected after dark—reminded us, at every turn, of how much humans have in common with objects. Mutability, for example. Like people, objects age and fray, break and disappear. We share their susceptibility to the beneficial or unfriendly effects of time. We assume that objects are less aware of the passing minutes than we are, but some things—clocks, metronomes, pendulums—are far more skilled at measuring its incremental disappearance. Timelapse surrounded us with things that, again like human beings, depended for their existence on a highly complex balance between delicacy and strength.

A kaleidoscopic, futuristic whirlpool, Times Zero was a massive wall piece—part paint, part collage—that reappeared, torn into shreds, on the canted floor below it. It was like a jigsaw puzzle assembled by someone only half aware that the pieces should fit, or by a tired child who decided to throw out the unsolved tiles. We looked back and forth from the vertical to the horizontal. What was missing? What happened to those hands that appeared on the wall but not on the floor? The piece provided additional proof: anything that is created can be unmade at any moment.

Like so much in the show, Times Zero brought to mind the marvelous quote from Tennessee Williams’s stage directions for The Glass Menagerie (1944): “When you look at a piece of delicately spun glass, you think of two things: how beautiful it is and how easily it can be broken.” Sze’s installations address change (both desirable and unwelcome) and evanescence: the pendulum hanging down into the rotunda would never mark the same moment or skim the same water twice. The potted plants would grow, the fountain would continue to burble, whether or not we were there to see them.

It’s been a long time since I believed that, in order to be a totem, an object has to possess the rarity and beauty—the intentionality—of the Venus of Willendorf, a Benin mask, a Cycladic maiden, a medieval reliquary. Timelapse reminded us that anything—a whirring desk fan, a blinking lamp—can be powerful, depending on where it is and what it can do. Small empty frames, strung on a wire, could mimic ritual objects, prayer flags, or the votive charms of body parts sold outside healing shrines. We can outgrow or cherish objects, spoil them, or treat them with loving care. The photograph that calms and cheers us can be summoned up on our phones, the photograph that breaks our hearts can be torn into shreds and discarded.

In Things Caused to Happen (Oculus), a tiny video, on one of the many small screens that had been set inside in a gleaming armature—a planetary metal globe—lit up with the pearlescence of abalone. We stared as if we’d been given a way to peer into the chambers of a beehive or the beating municipal heart of an ancient civilization.

The most elaborate piece in the show, in its own space in the seventh-floor tower, Timekeeper invited us into that place where, like Alice down the rabbit hole or through the looking glass, we enter an imagined world: uncharted territory strewn with objects suggesting that someone has been here before us. We were inside something—but what? Our minds, our dreams, our memories, our attics. We searched for familiar objects—a stack of books, a swivel stool, a digital clock, a water bottle—much as we scan a crowded room for a friendly face. But these objects no longer looked quite the same, removed to another existence on this crowded interior planet. It was as if everything we saw constantly, directly or at the far edges of our peripheral vision—the flickering screens, the ragged snapshots, those tangles of wire and ports and plugs on which our daily life seems to depend—had been collected, repurposed, and gathered in one place.

These objects—not only the scraps blown around by the fans—were in constant motion. Things were in a perpetual state of change. Video monitors became goggles, or the eyes of an alien creature hiding among the clutter. Lights flashed on and off, images materialized and vanished. All around us, museumgoers were looking through their screens, using their screens to photograph other screens, in case we needed more evidence that this is the way we live now.

The metronome, ticking, ticking—was it a help or a warning? There was something vaguely ominous here. The low-level thrum of anxiety and anticipation was something like what we feel when the lights in the planetarium go down and the vast, intimidating sky opens up above us. There’s that snow globe rush of excitement spiked by a kind of pride in what the artist has done. Humans are, as far as we know, the only species capable of imagining and fashioning complex alternate worlds.

One of my favorite things ever was to climb the staircase of the Breuer Building when it was the Whitney Museum and look out the window through which you could see Dwellings (1981), the miniature settlement sprawled across a landscape, made of clay, that the artist Charles Simonds built in a cornice in an elegant, two-story building on the other side of Madison Avenue. Dwellings provided a similar kind of pleasure as Timelapse.

We’re grateful for what reconciles us to the best aspects of what humans are and what we can do. At this fraught moment, we can’t help wanting affirmative evidence of our imagination, our capability, of what happens after that hand, in the recurring video, draws that first line on the page.

It’s not as if the natural world was absent from Timelapse. Someone at the Guggenheim had to be watering those potted plants. When I asked a friendly museum guard what she liked best about the show, she pointed to the potted bonsai and said, “I think all the green.” When a friend told me that Sze’s work makes her feel as if she’s looking at lichen under a magnifying glass, I thought of how a terrarium is another sort of snow globe. It’s mossier, greener, a glass enclosure in which things change and grow—but very very slowly.

The fleeting, almost wistful glimpses of nature brought to mind a sentence from Vladimir Nabokov’s essay on butterflies: “I discovered in nature the nonutilitarian delights that I sought in art. Both were forms of magic, both were a game of intricate enchantment and deception.”

Arranged throughout the exhibition were assemblages of studio equipment, presumably left over from the installation and possibly waiting to assist in its deconstruction: ladders, clamps, paint, scissors, spools of thread, brushes, paint, paper, all kinds of tools and detritus. Surprisingly, something about their presence cured me, or almost, of my allergy to the word process. Whenever someone asked, What’s your process, or I heard artists ramble about their process, something in me would die a little. Maybe because it felt like reducing art to a cookbook recipe or a list of satnav directions: do this, add that, turn here, do that. Here’s what I do. Try it.

Here, though, I liked the heaps of studio material strategically piled around the show—a welcome reminder that what we were seeing was part of a process, that it was created according to a process. Someone made this, it didn’t just fall here like the gentle rain from heaven. And it could be unmade according to another process, suggesting that what we are seeing is always a work in process.

Timelapse reminded us how much work is needed to make something that interests and satisfies the artist—and that someone else might actually want to look at. For all its apparent fragility, Timelapse carried a lot of weight: the complexities of consciousness, the mystery of time, an inquiry into questions that have no solutions. How delicate and random it looked—and how much labor it must have taken to achieve that. How hard these thousands of moving pieces must have been to arrange and balance and make everything work just right. And at a certain fixed date, the tools and ladders would resume their “true” function, facilitating the complicated move from the museum to somewhere else.

Someone put this here, someone would unmake it. Blink, and something else would take its place. The long-running installation will be in the mind of the viewer and on the Internet. In fact, quite a few video clips of the show are out on the web; the amount of movement in Sze’s work lends itself to video in ways that more static art cannot.

In an essay for the catalogue that accompanied the show, Kyung Ahn, associate curator for Asian Art at the museum, describes the lengthy process of bringing Sze’s work to the Guggenheim. The idea was first proposed in 2018. The show was scheduled to open in the autumn of 2020—but was postponed until this year because of the COVID-19 pandemic. For a project that took so long from conception to completion, Timelapse was very much about the moment—the historical moment, the cultural moment, the planetary moment, what a moment means, the speed or slowness with which each moment passes. The show gave us a lot to think about. As you walked down the Guggenheim ramp you might feel certain areas of your consciousness blinking awake out of sleep mode, just in time to notice how beautiful and fragile everything is, and how easily broken.

Artwork © Sarah Sze