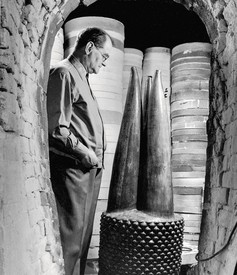

A potter since childhood and an acclaimed writer, Edmund de Waal is best known as an artist for his large-scale installations of porcelain vessels, which are informed by his passion for architecture, space, and sound.

Sally Mann is an American photographer and writer. Her work is held in many notable collections, including the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC; the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; the Victoria & Albert Museum, London; and the Moderna Museet, Stockholm. Mann’s Hold Still: A Memoir with Photographs (Little, Brown, 2015) was named a finalist for the 2015 National Book Awards and in 2016 won the Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence in Nonfiction. She was inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2022 and is a Prix Pictect laureate. Photo: Annie Leibovitz

Sally MannW. G. Sebald was talking about a picture of a young boy, and he said that the great tragedy of photography was that the boy had no idea what life held for him, the inevitable tragedies and sadnesses. It reminded me of that scene recounted by Herodotus where Xerxes is gazing down at his troops before him, this sea of men headed to battle, and he starts to cry. It’s the exact same thing. You realize that’s what photography does so well: it’s an elegiac art, a memento mori—always filled with pathos.

Edmund de WaalI love that. We have to talk elegy. And it’s interesting how central Sebald is to so many of us.

SMHonestly, he isn’t so central to me, I’m not that fluent in his work, but that quote stuck with me, especially in light of Sebald’s own ignorance of what was imminently to befall him—just like the boy.

EdWSo many places to start. Do you know that wonderful remark of Walter Benjamin’s: “I came into the world under the sign of Saturn—the star of the slowest revolution, the planet of detours and delays”? I kept thinking about our own work as being an art of detours and delays. I thought that was beautiful: the endless postponement of things [laughs].

SMIt has taken us a rather long time to get here [laughs].

EdWNot just this show, but the temporal thing. We’re endlessly moving around subjects, returning to them, and then iteratively starting again on them. I was so conscious that, in your studios a few months ago, I felt that it was full of beautiful, beautiful detours.

SMBut they’re always circling around the same impediment [laughs]. It’s just like Elizabeth Strout says: we all have one story to tell, and we tell it a thousand different ways.

EdWPerhaps one of the stories is the thing that you started off with, elegy, which is such a difficult place to begin any conversation. Or indeed end any conversation.

SMYour work has always struck me as having a sort of . . . maybe memorial isn’t quite the right word, but we’ll leave it at that: a memorial quality.

EdWI’ll take memorial [laughs]. It’s interesting, with elegy, that people tend to push it back to the ancients, to the beginnings of poetry.

SMWell, you think of it as spoken.

EdWYes, it’s spoken over, or sung over, so it has that feeling. But it seems to me that elegy is actually really difficult.

SMWhat are the components, do you suppose? Grace?

EdWGrace is interesting. Can you have an untidy, unfinished, sort of fissile elegy?

SMYou certainly can’t have facile elegy.

EdWYou can’t have facile elegy [laughs]. No, but grace is interesting. How can you have something that’s really, really beautiful and affecting, and deeply true to the person or the situation you’re being elegiac about, and have it not become too perfect?

SMDoesn’t it have to include a message from the past, in a way? Because it clearly isn’t speaking for the future if it’s an elegy, right? Doesn’t it by definition have to be an ending, a summation? Where’s Google [laughs]? Where’s our dictionary?

EdWIsn’t it about holding something that really matters to you. . . .

SMHolding it in your heart.

EdWIn your heart, and making it completely alive again in the moment. Having it revivified, reinvigorated, reconnected.

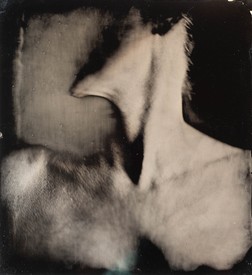

SMOne of the first things that I wrote to you was that we share this interest in materiality and alchemy, the way our materials are living, protean, sometimes capricious. Like clay, silver, and collodion—collodion especially is strange, with its little almost human frisson. It’s very finicky and transitory, and, just like clay I guess, it depends on the tension of the edges.

EdWThat process of the collodion, which I find fascinating, is profoundly about materiality and time and alchemy. You talk, somewhere in one of your essays, about screwing things up, about things going wrong, which seems to me absolutely the heart of alchemy: not ultimately being able to control a process.

SMOr, in your case, what you do so beautifully: you can mend it.

EdWWe can mend it. But ultimately, at the heart of it, there’s some sort of metamorphosis, something that isn’t controllable.

SMFor both of us. It’s utterly mysterious to me, even now, my craft. Yours is, of course, completely mysterious as well.

EdWWell, we have two opacities sitting next to each other. But there’s something shared about being obsessional about that return to that moment of transformation, in the darkroom and the kiln.

SMObsessional because we look for that moment of ecstasy, you know? And it can be . . . I mean, hell, I’ve been ecstatic over utter failure. And that’s a good thing, because there’s plenty of it [laughs].

EdWHow early did you put down the idea of the perfect image? It took me a long time to stop trying to make a perfect pot.

SMHow long? Do you mean decades, or years?

EdWAbout the first twenty-five years, I think. A couple of decades.

SMYeah, me too. I wanted the perfect print—and I still do. There are images that still require the perfect print, but there are images that just invite failure. How do you know when a project is finished? That’s the most common question, but how do you?

EdWWell, W. H. Auden says that a poem is never finished, it’s only abandoned. And abandonment is really important. You have to make space for the next body of work. You have to simply let it go.

SMDo you make a sharp break, or does it segue into the next? Does one lead inexorably to another, or do you put it behind you and say, Enough of this?

EdWI don’t know how it works. And the older I get, the less I know about how it works.

SMFor me there’s always the little siren song to create. Making and writing require the same degree of intensity and passion, but they’re so different. Writing wears me out. It’s exhausting. Whereas taking a good picture can in the moment be so exhilarating and exciting. You can’t wait to see what the next one’s going to look like and you can’t wait to get back in the studio. I can wait to get to the computer to write. It’s so hard to find the words. Although when you do, you do have that moment of epiphany and relief where you say, Yeah, I’ve just written a great paragraph. But different. Entirely different.

EdWBut you’re writing now?

SMI’m about to [laughs]. You know how that is, don’t you?

EdW“About to” is a wonderful space to inhabit [laughs].

SMWhat was that great quote I’d just read when I saw you in Virginia? This young guy turns to a veteran novelist and crows, “I’ve just written a book.” And the novelist turns wearily to him and says back, “I haven’t either” [laughs].

EdWYou know, having seen you at home, in the woods, with that turn of the river and the landscape, that particular landscape, and having spent some time with you in your studios, I got a very, very powerful sense of what place really means to you.

SMOh yes, it’s crucial. And what does it mean to you?

EdWWell, though I have no place that means so much to me, I think there are people who are completely deracinated and there are people who know what it’s like to love a place. And I think I’m the latter—I know what it’s like to love a place.

I suppose that you either have an impulse to dig or you don’t. So many of the journeys I’ve had have either been into bits of Europe on complicated family journeys, or into bits of the history of porcelain and the complexity of all that. But all those different places bring me back to an absolute imperative: to make something again or write something again.

SMWe claim our overlapping space, I think, our joint space, in this show. I’m so excited about this new work that you’re making.

EdWWhat’s so interesting for me is that—it’s a decade, isn’t it, that it’s taken us?

SMDamn near.

EdWAnd that’s quite a lot of reading and looking and conversations together in complicated places, and quite a lot of challenge as well, which has been really extraordinary. It’s not straightforward. It’s very much a self-generated thing, this idea of being in a space together and showing work.

SMDid I ever tell you how I hadn’t heard of you until Cy [Twombly] picked up your book—I remember exactly where I was standing in his house—and he handed it to me and said, “You and this guy have a lot in common.” “This guy.” I read the book and said, “You know, that’s true, this guy and I, we do have a lot in common.” That was a good moment. It was one of those auspicious times where you remember exactly what the sun coming through the window looked like.

EdWWell, I’m happy about that.

SMHe loved your work.

EdWIt’s funny, isn’t it? Because we did a conversation, you and I, together in New York, at the Frick Collection, in 2019. There was an audience, and it was the Frick, but in that hour together there was very much a sense that the world had completely disappeared. We were just thinking aloud and unpicking ideas and lines of thought. And you know, that’s sort of what’s going on in this show: unpicking different lines of thought.

SMTeasing out strands of commonality.

EdWSome strands weaving together and some completely passionate shared bits of poetry behind the whole thing. And there are these cadences between our work, which are really beautiful.

SMMixed metaphors, here. We’ve got cadences, we’ve got threads, we’ve got strands. . . .

EdWI know, it’s terrible. I mean, it needs editing, doesn’t it?

SMBlock that metaphor [laughs].

EdWBut there’s something absolutely at the heart: the elegy, the presence of memory within the work, which is completely unfashionable. It’s got nothing to do with any contemporary kind of stuff.

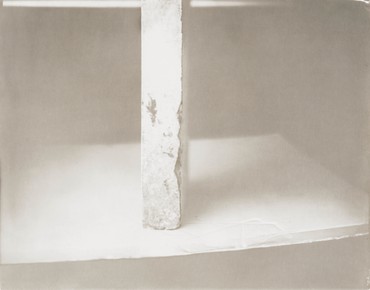

SMI think we both share the belief that objects carry memories, and that’s been so important in the work that I’ve done responding to your work, and vice versa. These are things that have heft and weight, emotional weight. When I chose what to photograph in collodion for our collaboration, it was all nineteenth-century stuff that was hauled out of barns or sheds or old workshops. But it had all been used, it had been held or passed down by human hands for generations, like a plowshare or a forged piece of steel from a blacksmith shop. All those things have resonance. They have stories.

EdWThere was a moment when I came to see you in the fall, and we went up to the neighboring farm where the owners had died, and the whole of the field around the house was filled with all their possessions, laid out. Every single agricultural implement was there, and the carpets and the household goods and the books and every single piece of crockery.

SMAnd the Bibles.

EdWAnd then another field was full of the cars of those who had come from all over to bid. And the guy standing on top of the truck—

SMThis great auctioneer.

EdWThe auctioneer, and several generations of a family’s life.

SMMore than several.

EdWMany, many, many.

SMSince the early 1800s.

EdWI remember writing something in The Hare with Amber Eyes [2010] about this moment when all these family things that hold all of these memories become stuff. The moment of their separation from a family and a place, this sort of diaspora of objects. We saw people taking things away from the field, but there was still some sort of resonance left in these objects.

SMEven within the dispersion of them. This is of course something you’ve explored in great detail in your work.

EdWAfter seeing this extraordinary farm sale, we walk into your studio and there are all these objects that over several decades you’ve been photographing again and again and again. It’s extraordinary because, of course, it’s not dispersion. It’s bringing them back together again in this powerful alchemical moment.

SMRight, exactly.

EdWAnd that’s how I write books.

SMMelding disparate things into one personal unit.

EdWYou couldn’t have choreographed that day more crazily, more perfectly.

SMThat day was so amazing [laughs]. I’m taking pictures in that house now because it’s just such a powerful place, haunted by—how coincidental—the souls of the local potter and his family.

EdWHow you talk about that, the presence of loss, how you talk about it as a real thing, not just as a kind of aesthetic moment but as a real elegy, a real holding of the past and bringing it forward into the present, seems to me very much at the heart of what you do.

to light, and then return—Edmund de Waal and Sally Mann, Gagosian, 976 Madison Avenue, New York, September 14–October 28, 2023