Sabine Eckmann joined the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum, Washington University, Saint Louis, as curator in the fall of 1999 and also regularly teaches seminars in the university’s Department of Art History and Archaeology, School of Arts & Sciences. Eckmann, a native of Nuremberg, Germany, is a specialist in twentieth- and twenty-first-century European art and visual culture.

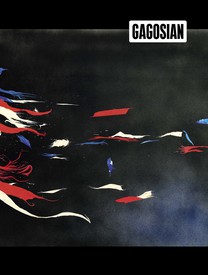

Katharina Grosse is a German artist who lives and works in Berlin. Embracing the events and incidents that arise as she paints, Grosse opens up surfaces and spaces to the countless perceptual possibilities of the medium. While she is widely known for her temporary and permanent in situ work, which she paints directly onto architecture, interiors, and landscapes, her approach begins in the studio. Photo: Max Vadukul

Sabine EckmannI’d like to start our conversation—which will jump back and forth between past and present, between your work and your interests, and between the ups and downs of life—with a simple question: what was it that made you want to become a painter in the late 1980s and early 1990s? Were there artists, theoretical interests, or experiences that led to this?

Katharina GrosseIn my youth I saw Wolf Vostell’s Fluxus Train, with its wolves with knives protruding blade-up from their stuffed bodies, at the Rothe Erde station in Aachen; I saw Pina Bausch’s dancers flinging their hair as extensions of their bodies; from Master Ma I learned tai chi and that strength comes out of the ground; and I first understood the Baroque through Bernini. As a child I went constantly to all kinds of plays with my parents and did not understand a thing, but then when I was seven I saw Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice: Shylock wants to carve a pound of flesh from the merchant’s breast, and suddenly the rest of the story becomes irrelevant—only this moment remains. I listened to a ten-second passage from [Igor] Stravinsky’s Firebird twenty times in succession, right in the same groove. I did that over and over again for weeks. And I clearly remember climbing in the Austrian mountains: how alone I was with the feeling that all these animals’ eyes were focused on me, with the sound of every falling stone ringing crystal-clear in my ears. At some point I realized that painting can bring everything together in a single moment.

SEWere there artist myths or role models that influenced you? The interesting thing about artist myths is that their connotations, of course, are entirely male.

KGPerhaps that’s why there were no role models, for I identified with all of the protagonists, of either gender. Even my childhood drawings show people in the center of the arena, as protagonists, with boxers and bullfighters photographed and spotlighted. I have never made a distinction between me and, say, the pianist Martha Argerich, but I identified with her and closely observed how her presence made the piano disappear and how the sounds just came forth from her identification with her instrument.

Ulysses and Edvard Munch were in any case of major importance to me—it was because of them that I traveled to the arctic circle on a cargo ship to see the purple shadows and the outsize granite cliffs. The goalkeeper in the 1974 West Germany–Holland World Cup soccer final was important, and so was the painter Walter Dahn, the guy in his underpants in the cold loft in Mülheim. I was always completely and relentlessly in the midst of it all, in the stadium, on the stage, in the film, at the concert—even though I can never agree with anything or anyone.

SEWhat made Dahn, of all people, matter so much to you?

KGI come from the Ruhr region of Germany, which was rebuilt in the 1960s, with construction sites all over the place. So as a kid you would spend the whole afternoon in a muddy puddle. Then I discovered this Walter Dahn character, who was looking for a role outside the society of his own culture—the wild man out in the provinces. That seemed to me like the artists who traveled to see the Hopi tribe, except it was on the outskirts of Cologne. Today I take a different view of all that, but back then I thought it might be a starting point for me—setting out from nothing, as if I had grown up in the forest like Parsifal, never having seen a Mona Lisa, and inventing something completely new.

SEDo you think this interest in an untainted new start at this point in time had anything to do with the historical situation in Germany?

KGOur legacy is National Socialism. It is our basis, which each and every one of us relates to, and which determines every social position we take. The fact that I started to produce abstract paintings was not some political message—it just happened. I wanted to get rid of the obstacles so I’d have more freedom to move. But this had nothing to do with the basis; it was something quite different.

At the academy in Düsseldorf, my teacher, the painter Gotthard Graubner, once told me I should look very carefully at what was happening within the picture field—what I was doing with it, and what could then be seen of my actions—and take responsibility for it. I should not look away from it, and that struck a chord in me. Indirectly it can also be read politically, though I didn’t do so at the time. I didn’t focus on what was expected of me.

SEIn the 1990s, Germany was clearly facing up to its past and renegotiating the present—a reunified Germany—in the light of this. In the 1980s, so much was unreflected—a throwback to the ’68 generation but without any real politicization. There was a detachment from political debate, though of course many artists thought of themselves as political artists.

KGI don’t see these developments so much as historical sequences but as a simultaneous whole: Cezanne’s incredible inventions, dividing houses and trees up into planes and reconnecting them, even making them interchangeable, with local colors; [Joseph] Beuys’s La rivoluzione siamo noi [We are the revolution]; Baroque painting; Bernini’s figures in Saint Peter’s Baldachin, with eye sockets so deep they stare out at you from the darkness. I think I began looking for gaps in which you can perhaps first experience yourself from the outside of society and conventions and you don’t have to take a fixed position straight off.

SEBut in Germany such strong individualism can of course also be seen as a kind of politicization, a reaction to the ideological collectivism of the Third Reich.

KGAs a child I played in Bochum’s youth symphony orchestra so I gradually got to know another kind of collective action. At the rehearsals we learned to hear the roles of the other instruments and how the most varied, often conflicting voices overlapped and interacted. We also performed pieces by Charles Ives, with parts of the orchestra let loose to play among the audience. Ives really fascinated me. There’s a story that as a little boy he was sitting with his father in a church tower, listening to four brass bands that were converging on them from all four directions, each playing a different rhythm.

I was also amazed by John Cage’s experimental, collective approach, merging into other people’s works. When he set his concert piano down at a New York intersection and played nothing at all for four minutes and thirty-three seconds, his composition fused with the community. He could simultaneously hear imagined silence and the volume of urban sound, and he invented as a symphonic concept the paradoxical overlapping of large, shared spaces, of sounds and movements that were not flowing in the same direction.

SEYou received your training as an artist in the last decade in which Germany was still divided—a period marked by the peace movement, the sluggish end of the Cold War, and fear of the rearmament of Germany, including with nuclear weapons. Could you already sense the historical upheaval that would lead to German “unity”? Would you say in retrospect that it shaped your artistic career?

KGRight then I was about to set off for a place I didn’t yet have any experience of. I was already turning my back on Germany. So I observed reunification as I was moving out, out of the corner of my eye, in a blur. I didn’t really think about it till much later, and that confrontation was one of the reasons I decided to begin teaching at an art school in the former East Berlin in 2000.

SEWhat part did your teachers play in your artistic development?

KGMy first teacher was Hans-Jürgen Schlieker, the head of the Musischen Zentrums at Ruhr-Universität Bochum. I was nineteen, and he said anything could happen in a painting. Johannes Brus advised me to work only with the material I had gathered together within the painting—to be economical. Reiner Ruthenbeck recommended Transcendental Meditation and humor. Norbert Tadeusz told us wonderful stuff about Joseph Beuys, his friend Blinky Palermo, and Tintoretto, and said the object in the painting should “stand in your way.” Graubner said you shouldn’t speculate, in art or in life. He basically said there were no choices other than complete surrender to your own predisposition. He admired talent and believed in masterpieces. At that point I could no longer go along with him. The teachers were all very authoritarian. What I enjoyed were conflicts and power plays. There was only one teacher I never tried to question; personal elements were relegated to the background, so the question of whether I accepted his authority never arose. That was my aikido teacher.

SEWho did you study with in Düsseldorf?

KGIf I think now about all the people who were there back then, it may seem crazy that I didn’t get on that bandwagon, but I didn’t—out of disdain for the art market, out of awe, maybe even out of boredom. In 1991, I went to Marseille. There I could start over. I didn’t run into anything of myself—no roots, no paintings I had gotten started on, no friends. I began developing my paintings more systematically from color and physical movement—recognizing that color can appear anywhere, is placeless. It was on my way from Marseille to Florence, at the Villa Arson in Nice, that I first saw large, glossy, brightly colored wooden panels laid out on the floor and obliquely reflecting the slanting daylight. The Swiss artist Adrian Schiess had gotten the panels straight from the store, in standard sizes, and had had them painted by an auto-body shop. Through the Galerie Conrads in Düsseldorf I came into contact with the Radical Painting group—with works by Marcia Hafif, Joseph Marioni, Herbert Hamak, and Rudolf de Crignis. All of this was new to me. And then through the Galerie Mark Müller in Zurich I got to know artists who had emerged from Constructivism, such as John Nixon and Olivier Mosset.

SEWhat about Color Field painting?

KGI didn’t have any clear strategic attitude to pictoriality—I didn’t meticulously organize the painting, the way Robert Ryman or Hafif and the like do. I had the idea that a painting should be present, meaning, should have a physical presence. I thought the materiality of the paint would do it. That’s why [Henri] Matisse’s very earliest works mattered so much to me, more than Ryman’s. In Matisse you can still see the weave of the canvas as well as the structure of the ground, but at the same time also the thick brushstrokes, with the physical paint as an element in its own right. This fascinated me, even in Matisse’s later work, when he applied the paint so thinly that you keep seeing gaps that expose the ground. He never ruled things out. This territorial meshing of colors and their changing effects interested me. You’ve got a blue patch of color and you paint a red one over it; this reduces the blue one, but it can still be seen, and it changes the presence of the red one. The sequence of choices and decisions that occur during the painting process suddenly allowed for experiences I couldn’t have imagined before.

SESo from the outset it was all about process and experimentation?

KGMy thinking in terms of process started when I began rearranging the color planes in the painting. For instance, I’d paint orange here and blue and green and yellow there, all with a thick brush. Then I’d remove the orange here and the green there, and then use a bricklayer’s trowel to put the two colors back in the opposite places. I kept on doing that with all the colors until the paint got smudgy—the painting became a mess. The colors kept changing places, and the more they changed, the more the traces of the changes were there. That was the first time I had used such an organized process when painting. It made me start thinking in terms of sequences. I had previously tried to paint everything in one painting.

SEYou said that for you it was first primarily about the physical materiality of paint.

KGYes. I eventually realized that there had been raw color in my paintings pretty early on, before I got to art school. When I painted a portrait I immediately saw orange, purple, green, yellow, and red in the face, rather than some flesh tone. And when I was doing this kind of “underpainting” I was so absorbed in the process that I realized that for me there was no background anymore—just ground.

In a recent conversation the philosopher Ludger Schwarte told me that I see the artificiality of color, that my use of color draws us into what he calls “something you can’t quite yet imagine.” And this something is precisely what is deadened by the images that surround us, that overflow us and determine our thinking. In those, color cannot be itself. He said I had given color a new power through which we can see images and perceive the world.

SEWere you trying to explore the basic elements of painting in order to generate new form?

KGAfter leaving art school I began looking more closely at my basic elements, and I realized that nearly all of them had changed over the years; only my use of artificial industrial paint remained. I’ve taken that further, omitting any notion of subject matter, relevance, conceptuality, or reference to a medium, using the unblended colors from the manufacturer’s palette as my starting point. I attached thick housepainter’s brushes to sticks and used them to paint large canvases in simple downward movements. I painted, going from left to right and back again, in a kind of endless wave movement. I started to get emotionally involved in the overlapping of the color movements. I felt like an arbiter called in to settle territorial disputes between yellow and blue. In the process of overpainting, or, in other words, when eliminating the existing layer, I developed ways to bring the underlying paint into contact with the upper layers, through overpainting, for example, like when you’re combing hair. Painting with a long stick also meant I could keep my distance from the painting and paint beyond the boundaries of the actual canvas. I could transmit movement to the brush from my whole body rather than just my wrist. The whole body’s momentum produced curves rather than straight lines on the canvas. And then what I saw was subordinated to adaptive invention—for instance, tonal value mattered more than what I could see figuratively, like a nose or an eye.

SESo you weren’t interested in something like Jackson Pollock’s allover approach, but rather in the complex and to some extent interlocking relationships between layers. Again and again, you focused on these complicated, unexpected interactions between layers of paint, reversals of surface and subsurface, and the autonomy of colors and their optical effects. But at first did you also paint figuratively?

KGI came to Düsseldorf with big, unfinished self-portraits, only the head, 98 ½ by 70⅞ inches. Then I painted and painted; the colors grew more and more intense and the image of the head vanished. As I overpainted and erased, I grew more and more involved in the actual brushstrokes, and I began to apply the paint in these really thick layers, like some weird [Alberto] Giacometti-esque kneading of the face. In fact I often navigated my way through Giacometti’s spatial drawings, in which all the lines reconverge as in a bulge on the face—his frugality, the anticolor, the clayiness in his work. . . . I once also spent a summer painting trees like Cezanne. It was constricting; it required lots of control on all levels to find out what drew me to his pictorial idea and what involuntarily controlled me. The question that came into focus for me at the time was, What is the power structure in which we act and create, and to what extent can we break free from it?

SECezanne also worked with patches of color.

KGYes, I could especially sense him touching the canvas, swapping locations and distances in his paintings. Something far away comes closer to you and yet remains unclear, as if you’re looking through the wrong end of a telescope. Cezanne familiarized me with the unfinished painting, the proposal that may claim consequences. With Munch and Lovis Corinth, the vehemence of touching the canvas is unconcealed and liberated. The effect of their pictorial interventions juts out into space and is disconnected from the painting. Lucio Fontana was also important for me—his early ceramics, but above all his Concetti spaziali, in which he made slashes in the canvas.

SEI can also relate to your interest in Fontana, since you’ve painted these canvases with successions of really thin lines.

KGI was fascinated by the sense of inevitability that Fontana achieved with so little effort.

SEWith him it is also about space, which he created by slashing the canvas. Of course, you can also create space by juxtaposing two different colors. Did that interest you?

KGNever. Not at all. In my work, spatial perception has to do with the negotiation of what leads to the painting and into the pictorial plane. In my blue-and-yellow paintings from 1992 and 1993, the yellow pushes in from the side, and afterward only this tiny slash of blue is left, so the painting is a passage, a flow. The curvature of the surface created through the movement of the brush extends beyond the border of the painting, or penetrates it from the outside. That my painting came to occupy the space beyond the canvas was my first accomplishment in Italy. I started the painting with the goal of shifting it into real space, and for the first time I felt that I was working in an area that felt right to me. The painting extending into reality is just as present as the man in a suit standing in front of the work, whose shadow is just as present as he is.

As a child I always played a game with myself in which I had to remove all the shadows before getting up in the morning. I invented an invisible brush to paint them out on the windowsill or the bedside lamp. It became an obsession. Looking at the world has always been associated in my mind with simultaneously doing something in it, with it, or on it.

When pictorial space encounters plastic space, common principles normally repelled by each other become interlocked, for instance when I overpainted the five-mile rail corridor in Philadelphia [psychylustro—The Green Passage, 2014].

SEYour focus shifted to the interweaving of color and space. Did you have anything particular in mind?

KGMy point was that you can’t evade the painting, that it comes really close to you, like it’s right there in your eye. You aren’t hindered by describability, which creates distance. Painting is not some reference or derivation—it enables you to see reality in the raw. You’re confronted with a sense of reality that’s not a secondary version of a more “real” reality, or a story thereof.

SEIn your grid paintings of 2006 and 2007, were you trying to achieve something other than perceptual vibrations, the optical spatializations that are intentionally much more pronounced in Op art?

KGI wanted the overpainted and underpainted colors to be interwoven. I wanted to let you see into this mesh of colors. This led me to the simultaneity of all colors, with the manufacturer’s palette restricting my choice of colors. Painting allows the simultaneity of imagining and acting in an unusual way, because there’s no transmitter between me and my tools. When you’re painting, you get clusters that cannot be read in a linear or causal way. They create a paradoxical experience, for layers appear in the painting, but there is no beginning and no end, no duration, no cause—for the viewer, there is only absolute simultaneity. Only painting provides these opportunities to view it at once. These are now the main conditions for my way of working.

SEWere you trying to undermine traditional structures (painting is often explored in relation to time) or hierarchies (foreground and background), or were you more interested in testing painting, or the properties of colors and their relationships to each other, over and over again? Did you want to transcend accepted boundaries?

KGBoundaries are constantly re-created negotiation spaces. My paintings provide models for thinking about border areas in which mutually exclusive vital interests often meet. Places of crisis . . .

SEAre the grid paintings a break with your previous work, or a further development of it? You used to relate patches of color to each other. In the grid paintings you tried to make the interweaving of colors visible. Do they make boundaries porous?

KGYes. Precisely. While painting the grids I walked around on the canvas and stepped in the wet paint, redissolving the grid. Suddenly there was a simultaneity of the grid and the marks of my steps. I had shoes made specially, with rubber plates attached to the soles, so I was stepping into the wet paint but nevertheless leaving no footprints.

SEWas it the dissolution of boundaries in your painting, as you have described it—during your stay in Italy—that led you to your spray paintings?

KGIn the grid paintings I was walking into the painting from outside—from the world into pictorial reality. The painting is ground down by the world, and vice versa. While spraying I realized that I can make something in space that’s quite different. I end up in between the world and the painting, without the canvas as a partition. I can use the spray gun to move nimbly past obstacles into our world and our social fabric. Color is atopic, not bound to a particular surface or place. It can end up anywhere. The paradoxical simultaneity of painting and the world becomes possible—something I first tried out when I painted over everything in my bedroom [Das Bett (The bed), 2005]. And I ask myself how painting can become present in a specific place—as an intimate expression, as an expression of an individual position that can be ascribed to a body and whose process of emergence is nevertheless unconditionally permeated by the needs of the community.

SEThe social anthropologist Julia Eckert recently described very precisely this expansion of your painting into the social fabric [“The Given and the Possible,” in Katharina Grosse: It Wasn’t Us (2020)]. To her, looking at a painting also means seeing suggested solutions. The picture plane claims the same value of the real as lived reality and thus can suggest solutions. What confronts us in your work is the assertion that it is possible to create new things within what exists and to pursue what has never been imagined before. The world looks different in your works, and we can see it differently. The old boundaries remain visible but lose their relevance; they are no longer boundaries per se, for they can no longer direct our observation, no longer channel our action. So your painting can be seen not only programmatically but also as method and methodology—as a practical way of exploring what is possible in what exists.

You have also used spray paint for canvas paintings. The different steps in the painting process can no longer be retraced. I’d like to know to what extent this was accidental or deliberate—or didn’t you care?

KGA stencil creates a hole; it functions as a gap in the act of painting. Using a stencil is the opposite of smudging. So you get a crack, a fault, and an unconfined space that you can get into from anywhere. In Saint Louis the large-scale, in situ painting I did in 2016 in the Gary M. Sumers Recreation Center, for instance, intersects with the architecture of the building, i.e., with the big picture, and this in turn with the mirrors, i.e., with a slightly smaller picture, and with the glass of the display cases. And this even smaller picture intersects again with the bridge, the main entrance, the office doors, and the bushes outside.

SECan it also be described as a fracture that destroys homogeneity?

KGYes, it can.

SEIn the paintings you exhibited at Gagosian in New York in 2017, such fragmentations are very clearly elaborated. The viewer just cannot retrace how the painting was developed. At the start of your career, perhaps until the tondi [from 2005] first appeared, your work was transparently procedural or processual and so more or less trace-able. But this does not apply to your current paintings, which makes them all the more alien and complicated.

KGNot being able to retrace them also means there’s something I’ve failed to grasp. It’s something strange that I have to confront, but the real point is that I overload the surfaces to see how far I can multiply them within a small initial field. That’s quite different from painting outdoors, where the visual field is stretched out, as in slow motion.

SEIn this connection I’d like to discuss the moment of absolute simultaneity you mentioned before. Without chronological time, without a recognizable process, there are consequently no utopias for the future but also no comprehensible past. Would you agree?

KGYes, you’re right. The layers of time are interchangeable, but they open up hitherto unimagined possibilities.

SEYet time sequences play a part in your paintings. That’s a very dynamic working process. On one hand there is this theme of retracing and untraceabilty, and on the other this flexible, non-goal-oriented method that can be strictly analytical and is paradoxically unpredictable.

KGThrough various revisions as I paint, I find myself in a role I cannot help abandoning. So you have both: getting bored with your own reiteration, and wanting to leap into the unknown. I give it a try, and at first it may look like an illustration, but then, six months later, there really is a painting. What I certainly never do is develop an idea and then try to visualize it.

In the philosopher Simon Critchley’s book about soccer [What We Think about When We Think about Football (2017)] there’s a chapter with the amazing title “Repetition without Origin.” In it he quotes Hans-Georg Gadamer’s comment that it isn’t the players who play the game, but the game that plays the players.

SEI was also thinking of Bruno Latour and his actor-network theory, in which color itself becomes the actor.

KGI would agree. Everything is an actor: color, time, the machine, all the elements.

SESo there is no passive counterpart?

KGNo, there is no counterpart; all the players are equal.

SEAlthough of course you influence them.

KGThat’s totally variable. Sometimes one element has more influence on the other, and sometimes it’s the other way around. That means the experiment is defined by a really tiny percentage of the experimentation; the field of the experiment is open to worlds whose course is unknown to you.

SEThat’s so interesting. Has this openness played the same part in your work from the beginning? Did you always simply let what happens on the canvas unfold?

KGI determine the beginning and the basic conditions very exactly, and then the developing chain of decisions can lead to openness—a process that involves matching up my inner and outer orientations.

SEI think all openness in the artistic process is also controlled, as is what some would call “chance.” But you have to make room for this openness or else the whole thing becomes dogmatic, formulaic.

KGThere’s a point where something tips, where you’re aware of a change in tension. And suddenly what you had in mind is no longer visible but a blind spot, and what you did not want has become all too uncannily visible. And I also include what can’t be related to the original idea. That’s why I think it’s pretty misleading to define my work as abstract. I think it’s more about a tipping or reversal point, at which one form is encapsulated in the other so that we aren’t talking about either/or but about a paradoxical simultaneity—about forces that seem mutually exclusive emerging at the same time, like the architectural space and the superimposed pictorial space in the green corner at Kunsthalle Bern [Untitled/o.T., 1998]. They don’t eliminate each other.

With this paradoxical simultaneity I’d like to achieve a reorientation. There has to be a space where you can finally begin to talk and to think beyond binaries and conventional categories and definitions. Back in the time when I did not yet see this so clearly, I focused on questions of pictorial development, and on tradition, which has no readymade role for me. Can expressions of interest arise without being tied to definitions?

SEOf course, it also depends on the context in which you see yourself. That’s not always easy. It would be dogmatic to say you’re a woman and because of that there are now no examples or models for you to follow.

KGSam Gilliam said, As an artist I’m not a Black artist, but as a social subject, of course I’m Black, male, and Sam.

SEYou can see yourself in an artistic context, and also in a sociopolitical one, and yet sometimes the prevailing sociopolitical context doesn’t matter so much. For instance, while Germany was reunifying, you were on the move and being exposed to quite different contexts.

KGOr I may have deliberately avoided them, because I had relatives in Leipzig and Dresden, in the former East Germany. I was often there as a child; I remember sending them parcels, and my relatives also lived with us. Perhaps I felt I knew all that—and I preferred Italy.

SEThat’s why it matters how much you acknowledge your own context, which doesn’t always have to match the predominant story. In your case there are some fairly striking discrepancies—for instance, you were interested in someone like Dahn, instead of focusing entirely on the art of Rosemarie Trockel.

KGWhat attracted me, and what didn’t? I was fascinated by virility, and shocked that as a characteristic it could not apply to me as a woman, it excluded me. Such exclusion is unfair, a prohibition, a massive rejection. All I wanted to do was paint. As a female painter I had to work in a field whose proponents saw me as an intruder, and in which I had to remain unnoticed. The resistance you can sense in this rejection riles me and irritates me. I always want to see what’s possible in what exists. Your question also shows how narrowly the boundaries can be drawn in the artistic context, while in reality our everyday lives are marked by many other contexts and follow social logics other than those of boundaries. Boundaries deny what is possible; they generate fear, and they sever the entanglements within which we live.

Translated from the German by Kevin Cook.

Originally published in Katharina Grosse Studio Paintings, Three Decades: Returns, Revisions, Inventions (Berlin: Hatje Cantz Verlag; Saint Louis: Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum, 2022).

Artwork © Katharina Grosse and VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, Germany 2023