Derek Blasberg is a writer, fashion editor, and New York Times best-selling author. He has been with Gagosian since 2014, and is currently the executive editor of Gagosian Quarterly.

Derek BlasbergWelcome back from Venice and congratulations on being the first woman and first costume designer to receive the Campari Passion for Film Award at that prestigious film festival.

Arianne PhillipsOh gosh, that kind of stuff is so nerve racking. To be honest, I’ve been nominated for a few things over the years, like Oscars and Tonys, but I’ve never won. But this wasn’t a nomination—I knew I had to go up there and prepare a speech. It was a whirlwind trip because I’m working, but I was super excited to be reunited with everyone from Don’t Worry Darling, the film I did the costumes on that premiered at Venice.

DBIf someone asked me what a costume designer does I’d say it’s the person who picks the fashion for films, tours, and photo shoots. How would you describe what you do?

APCostume design, specifically, is character building, which in turn is part of the cinematic storytelling process. Fashion, on the other hand, I believe to be a reflection of the culture at any given time.

DBThat’s a much better definition.

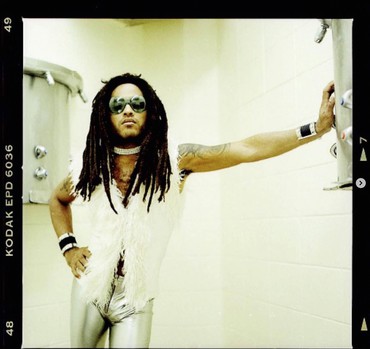

APIn film, it’s very specific. I crafted a career between disciplines by choice, I guess you could call it creative ADD. Ha! I started trying to work in fashion when I first moved to New York, and then met Lenny Kravitz through mutual friends he knew from high school.

DBWhat high school was that?

APBeverly Hills High, of course.

DBOf course!

APWe met before he released his first record. He was playing drums, traveling around with New Edition and Teena Marie, we were friends, and he was like, You know, when I make my own record, you can be my stylist, and blah-di-blah-di-blah. But! It actually worked out, he did end up making his own record and I did end up being his stylist.

I went into fashion initially because I love print photography. You can look at style and know so much more than just clothes: you can look at any fashion magazine from any time—a 1950s Vogue, say—and know what was happening in the world then and what was in the zeitgeist. That’s the thing that’s so exciting, it’s not just about what’s beautiful—it’s also about that, of course—but it’s about relevance, it’s about dreaming. I love the art of fashion.

DBUnlike some other art forms, fashion has to be collaborative.

APThat’s what I also loved about editorial work: working with photographers. I have some amateur photographers in my family and I grew up looking at books by Diane Arbus and all of these inspirations in photography. That was art for me! And then when I met Lenny, all of a sudden I was really excited about having that influence of dressing someone to help create a visual language around a musical artist. MTV had been out for less than a decade; as a kid, I was obsessed with MTV, and that became my dream, I wanted to work on videos and MTV.

DBYour dream came true, Arianne!

APThe great thing about music videos, and working with Lenny, is that you’re given the opportunity to tell a story. With performance videos, when someone’s singing and you’re making them look hot and sexy and appealing, that’s easy with someone like Lenny. But when we did a video off his first record for a song called “Mr. Cab Driver,” it was a narrative video that was telling the story of the song. Suddenly I had to dress this guy as a cabdriver, and I just had to think of it differently. What does a cabdriver look like? I realized that the visual identity of a character and what they wear can say so much, even in real life. It was an epiphany for me about the medium of clothing and how it can illustrate an idea or a tone or a character. That was really intriguing to me, it lodged in my young forming brain, and I knew there was something there that I was really interested in.

DBLenny Kravitz as your first job? Not bad.

APTotally. Before that, when I was growing up, I was a theater kid. When I was twelve years old, if you’d asked me what I was going to be when I grew up, I was going to be an actress. I was really involved in community theater and I was obsessed with things like The Wiz and Hair. I did this movie in 2000, Hedwig and the Angry Inch, and then fourteen years later they brought it to Broadway with Neil Patrick Harris, and I got to have that experience [of designing the costumes]. That opened up opportunities for me, and I’ve since designed a few musicals and an opera at the Met. For me, it’s always about the mix and a new challenge and keeping the work fresh. The medium’s always clothing, so whether it’s fashion or costuming, I always feel like one informs the other, and that’s what sustains me. Otherwise I would probably have burned out years ago.

DBWere the arts, either contemporary art or more museum culture, a part of your childhood?

APAbsolutely! First of all, both my parents are artists. My mom is a painter and a writer, my dad is a musician and a writer, and I was raised in bohemian Northern California. I was born in Greenwich Village in the 1960s and then my parents moved to Haight-Ashbury[, San Francisco]. So I’m a product of this kind of youth-culture movement that my parents were part of. They weren’t really hippies, they don’t like to be referred to as hippies, they were more like intellectuals, bohemians. I was raised going to poetry readings. It was the 1970s, and very experimental, and I was exposed to a lot of art, a lot of opera, a lot of theater. My parents absolutely encouraged me to follow a creative career where I could express myself; there weren’t the same kind of expectations that their parents had for them to lead a more traditional, safe trajectory. They gave my sister and me a lot of space and encouragement.

DBThat’s wonderful. In many ways that’s a gift.

API was talking a lot about Don’t Worry Darling when the movie was coming out. It’s set in the late 1950s, early 1960s, and the film is really crafted around mid-century design. As a costume designer, I always start being inspired by color and silhouette, and for this film I was looking at the color of Mark Rothko and a lot of mid-century artists, the energy of Jasper Johns, when I was choosing my prints. In the conceptual stage I always look to art. When I was working with Madonna, a lot of our conversations before tours were conceptual, and we were inspired by the most conceptual art rather than figurative art. Art has always been really helpful to me, just in terms of evoking mood and tone, which is really what costumes do in a film. Not that everyone looks fashionable in a film, but I look to fashion as a point of relevance for a certain time period. Oftentimes you’re creating something that doesn’t exist, that’s a fantasy, and actually you can look at fashion for that; other times you’re telling a story that’s not necessarily a beautiful story.

DBDo you have favorite painters or artists, and have you ever worked with them in any capacity?

API’ve worked with a lot of art photographers and I love art photography. My dad’s first cousin, Jo Ann Callis, is a really amazing artist, her work is incredible. I’ve worked with Alex Prager and Tierney Gearon and Jeff Burton and all kinds of artists who aren’t traditional fashion photographers. That’s always been really exciting to me. One of the reasons I’ve kept my toe in fashion, and why I like working in fashion, is that I love working in tableau form and I love the symmetry, the balance of quietness, of working with a photographer. On a film there can be 150 people on set; I like the intimacy of working in photography. Although, if you’re shooting with Steven Klein, there can also be 100 people on set because he loves a big production, ha! And I’m inspired by all kinds of artists, the sky’s the limit, you know? I’m always looking for color inspiration, whether it’s Lucas Samaras or Joseph Cornell or Jean Crotti. I have a contemporary-artist friend, Marc Swanson, who has a big show right now at mass moca and he uses multimedia work and it’s really inspiring. I love John Currin, Francesco Clemente—I mean, it’s endless.

DBWhen I started in fashion, in the early 2000s, there seemed to be a disconnect between contemporary art and the fashion world, which I think has dissipated over the years. How do you feel about the relationship between the fashion world and the art world?

APIt’s so interesting you say that because when I moved to New York in the mid-1980s, art and fashion were fused. Andy Warhol was around. Some of my first jobs were working the coat check at the Palladium and Area clubs and there was so much art in contemporary fashion. Jean-Michel Basquiat would be there! There’d be art installations at the clubs, especially if you dig up the old pictures of Area. It was insane. I moved to New York in time for the last six months of Area and they had these amazing performance artists doing installations. The artists were socially part of that scene in downtown New York. I did a lot of editorial for a magazine called Splash, a downtown art-and-fashion magazine, and it was really great, and it was equal page time for art and fashion.

DBI love those pictures of Basquiat walking fashion shows.

APAbsolutely! There was no separation between what was happening in the art world and what was happening in downtown New York. It was very, very exciting. I worked midnight fashion shows at the Palladium for a crazy promoter, Steve Lewis, and I was obsessed with anything street culture and English fashion. [The English magazine] The Face was my Bible, I loved English pop music, and these designers like BodyMap came over from London and did midnight fashion shows. That’s how I met [photographer] David LaChapelle, and all these kids I hung out with at the Pyramid. I was a dresser at those shows! There were really no limitations—I don’t know about the rest of the city but for what we were doing it felt like a very optimistic time. Or maybe that’s just a gift of youth, when everything can feel possible? That really informed my own trajectory. I was told time and time again that I needed to pick a lane in terms of what I wanted to focus on, whether it was fashion or music or costume, and eventually I moved to LA because I just felt like I had to figure out who I was creatively.

DBBut you’re still doing them all!

APYes, and I will say that all that experience starting out in New York as a young person informed me, because I didn’t want to make a choice between one discipline and another. I was trying to figure out how I could kind of do it all. I guess it was greedy of me!

DBIt’s funny that you say that you went to LA to figure out what you wanted creatively. I think some people would argue that they go there and lose their creativity.

APTo be honest, I didn’t have the strength of character to choose in New York. So many people were telling me I had to focus, and had to either be a fashion editor or go work in film or work with musicians. “You can’t do it all!” I mean, I was twenty years old and I was a college dropout. I knew I had to hustle or my parents would never talk to me again. I felt I had an opportunity—Los Angeles might as well have been another country and I didn’t feel as influenced as I did in New York. In LA at the time, there wasn’t a lot going on, and that gave me the ability to have some autonomy. I was able to build my career by following projects that felt right for me without feeling a social pressure. And then LA started to grow up and we kind of grew up together.

DBThe LA art world is much different now from when you moved there.

APBeyond different! New galleries, new communities. I mean, the Broad! Hello! People from New York started moving. I’ve been here since the mid-1990s and LA’s gone through a huge transformation.

DBI see that you’re at work now. Can you tell me what project this is?

API’m in the Valley, at Western Costume. I’ve just started prepping the follow up to Joker, which is called Folie à Deux.

DBIs this the one with Lady Gaga?

APYes!

DBThat’s awesome! Presumably you’re immune to the charms of celebrity, having worked with so many great stars of the stage and screen. But I guess that’s still exciting, no?

APActors, performers, for sure—I mean, I’m always excited to work with a talented performer. It’s the second time I’ve worked with Joaquin [Phoenix] so I’m really excited to work with him again. We did Walk the Line [2005] together. I adore him.

DBI know you’ve worked often with Madonna.

APYes, many times. And with her there’s this fluency of influence, that’s why it’s so great working with her—she’s rigorous when it comes to her influences. She’s influenced by literature, by art, by music. Being able to have that mind-meld with an artist, and being able to move through genres, is super rare. I’ve worked with her on tours and on album covers and in editorial shoots, and also as a director.

DBWe can wrap this up now but I have one more question for you: you’re wearing a hat that says “Willem de Kooning” on it.

APThis hat is actually from a young designer I consult with, Henri Levy, who has a store in Paris called Enfants Riches Déprimés. I met him through Courtney Love. I was just with him this weekend because I consulted on his show. I think he’s great and when we finish here I’ll send you more info on him.

DBDid you wear that hat because you knew I was going to ask you about art in this interview?

APHonestly, no. I wore it because I’m having a bad hair day.