Ester Coen is an art historian and curator. She is an expert on Italian Futurism, the Metaphysical artists, and the international avant-gardes, and her research for her numerous essays and publications extends from the 1960s to the contemporary scene. She has curated many exhibitions, their subjects ranging from Giorgio de Chirico, Umberto Boccioni, Giacomo Balla, and Henri Matisse, to Richard Serra and Gary Hill.

RECOVER, RECYCLE, WHIRL

Recover, adapt, repurpose, recycle, reuse, spin, whirl, twirl, swirl. The continuous, tumultuous, unsettled, irrepressible principle of the universe is to be in continuous transformation and constant disturbance. Sterling Ruby likewise collects, amasses, accumulates, throws together, then observes. His studio contains many piles of materials subdivided by type, a crazy collection of things and forms that have already experienced other places and spaces; in these abandoned structures Ruby finds something capable of rekindling the potential for energy, which otherwise at this point has vanished. He identifies something these things share, something to be prodded and extracted from the apparent inertia. It is a new phase of creation—a different phase, but still in line with the extraordinary vitality of Ruby’s work.

Ruby is a politically accountable artist, engaged in questions of racial and gender equality. Analysis of his collections of materials and scraps might allow one to trace a visual map, historical and universal, and to extract from it materials for a denunciation; and then to find the strength to reactivate the positive value of things through systems of heterogeneous realities, weavings of new relationships—all rather more complex than the auratic nature of an individual creation. All Ruby’s originality and tension focus within this two-faced-Janus vision, where past, present, and future coincide in a single glance and where past and future run along the same line of continuity. This simultaneous synchronism revives the conceptual resolve of the early avant-gardes, those inclinations that, in rift and rupture, identified a model for transforming forms and languages—for a metamorphosis of existence.

THE SPELL IS BROKEN

Si è rotto l’incanto (The spell is broken): during a recent visit to the house, in Rome, of the Futurist artist Giacomo Balla, which still shows traces of his protean activity, Ruby encountered this painting from 1920. Si è rotto l’incanto is made up of variations of a single color, a pink that intensifies until its tone swells into a strident bright fuchsia. In stratified planes marked by simple geometric forms, one glimpses black lines that modulate until they blur into a transparent gray, creating an illusory sense of three-dimensionality. They twist and turn in the space, wedge into it, harpoon it, then reassemble as if articulating a fleeting figure, or the wings of an imaginary pinwheel, springing the entire surface into action. In its simplified principles and metrics, Si è rotto l’incanto is highly modern, while at the same time, through the complexity of its composition, it is labyrinthine. Even more modern is its use of a color that, a century later, is charged with ecological significance: chromatic testament to the survival of the ecosystem. The most ancient colors in the geological record, found in rocks deep in the Sahara, are pinks, the “molecular fossils of chlorophyll that were produced by ancient photosynthetic organisms inhabiting an ancient ocean that has long since vanished,” according to Nur Gueneli, a paleobiogeochemist at Australian National University. The Pantone shade 1775C is based on that pink, the company’s “color of biodiversity” for 2023.1

A TIME TO EVERY PURPOSE

There is a time to every purpose, scripture tells us—but in current thought that time is no longer seen as fixed and universal. Instead, contemporary scientists see a dynamism between multiple times: the temporal structure of the universe does not coincide with individual perception and experience, yet we can intuit a sense of duration, a congruence between existence and what we perceive as the passage of time. With all our knowledge, increasingly sophisticated devices, and advanced scientific data, the nature of time remains mysterious, even today, and in that dimension of mystery it is intrinsically interwoven with the infinite other mysteries that accompany our existence—mysteries to which philosophers and scientists have sought answers for millennia, always returning, after fascinating hypotheses and endless approximations, to the original question.

That question transcends and traverses centuries, annulling times and generations to arrive at an incredible correspondence: the affinity between pre-Socratic philosophies of nature and the extraordinary modern discoveries around relativity. Between Anaximander, in the sixth century bc, and Albert Einstein, in the twentieth, we find a surprising temporal loop. Even when the only fragments and slivers remain of ancient hypotheses, even the aphorisms surviving are enigmatic, they are always fascinating. Anaximander, for example, wrote, “Things transform into each other according to necessity and do each other justice according to the order of time.” The calculation of time, then, is correlated with the transformation of things and events in sequences determined by necessity. Centuries later, Einstein measured the evolution of one time according to quantities correlated to others, denying the uniqueness of any single unit of measure. His theses were seductive at the beginning of the last century, when the science of the time was colliding with an ancient and obsolete past. But how can one help but react to surprising scientific revolutions in a world in transformation, imagining an art capable of representing the frenetic rhythm of the contemporary moment, and the elusive essence of its energy?

MIXING TIMELINES

“I’m mixing timelines.”2 Ruby draws a temporal parabola with an immeasurable range, a trajectory launched into the present but journeying back among innovative and radical signs and expressions until, ideally, it touches the deep heart of the universe. The encounter with Futurism occurs along these material coordinates, pantheistic and conceptual. The Futurists called themselves “primitives of a new sensibility”—a violent, impetuous assertion, apparently contradicting their idea of modernity. With the power of a primordial thought, the statement holds a strong creative tension, and the Futurists wanted to include the essence of that dynamism in painting. To recover that tension is to rekindle the full potential of a visionary impulse, suggesting a sensibility that reconnects and synthesizes every moment of history, making the weight of the past a legacy for the future, making inventories and repertoires the foundation for new inventions. “I had this idea that my work was operating between expression and repression, and I wanted my work to represent both. I saw my work as an intermediary between law and crime, old and new, future versus past. I wanted the work to be a balance of these things.”3 Looking back to move forward, uniting opposing forces by creating frictions between them without canceling their potency, maintaining the intensity of contrasts at the moment of their clash: Sterling reads these polarities as his own character traits. They highlight qualities of an artist engaged in weaving narratives of the present through the imaginary metaphors of art.

AVANT-GARDES

“I always looked at the Bauhaus as the most significant historical movement. I love Russian Constructivism. I love Vladimir Tatlin, I like El Lissitzky, Kazimir Malevich, Lyonel Feininger, Theo van Doesburg. They represent a nonhierarchy.” In the imaginary map that Ruby traces, references to artists and movements are references corresponding to his own consciousness. The places, times, and figures he chooses express moments, occasions, circumstances of independence, of freedom, of study. Constructivism: the projection of a social model of autonomy freed from the logic of power. The angular sculptures and pictorial reliefs of Vladimir Tatlin include his Monument to the Third International, of 1920—the same year as Balla’s Si è rotto l’incanto. The structure makes a political proclamation as enveloping as the spiral on which it unfolds, in a continuous geometric succession—a “divine” or golden proportion that tends toward infinity. In the thirteenth century, the Italian mathematician Fibonacci translated exponential growth in nature into a mathematical formula that finds the same constant in shells, sunflowers, snowflakes, eddies, cyclones, galaxies.5 Ruby too translates a constant in his new

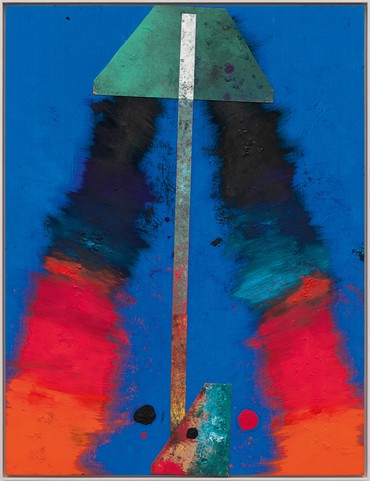

turbine series: “I wanted these paintings to feel turbulent, frenetic, and convulsive. I keep asking myself, how can I make something that inevitably reflects the charged time in which we live, to evoke a political tension, without being explicitly bound to that interpretation?”6 El Lissitzky’s collages, his Proun works, explore the limits of painting, expanding toward architecture in their complex constructions of axes and perspectives. But Ruby goes further: he stitches up the threads of that history in rotations of colors and elements whose frenetic beats evoke a disunited and tragic musical tempo, the zenith of a contemporary conflict.

LINES OF FORCE

“We stand on the last promontory of the centuries! . . .Why should we look back, when what we want is to break down the mysterious doors of the Impossible? Time and Space died yesterday. We already live in the absolute, because we have created eternal, omnipresent speed.”7 Filippo Tommaso Marinetti’s explosive Futurist enunciation of 1909 came in the wake of astonishing scientific discoveries and in the spirit of a new time, the mechanical era that aimed to supplant the slow biological rhythms of nature. In reinterpreting twentieth-century artists and movements that have left a significant mark on art, Ruby chooses those that respond to his own experience and that offer, including from a formal perspective, a prod of momentum that can still stoke and trigger preserved energies. If the strong initial thrust is the power of identification, its suggestions pass through various levels of metamorphosis until they manifest in the traces of a thought, a motivation, an empathy, not as elements ripped from the past and translated into a modern lexicon but as shadows to pursue and revitalize. How, then, is it possible to freeze those images, at this point transmuted into the fluid fragility of malleable materials, the free spatiality of metallic reflections, the opaque translucence of salvaged and reassembled ceramics? How do we attach them to a place, a history, a time that is no longer linear and uniform if not through a frame, a series, a play of vectors and lines with strong directionality and visual impact?

ENTROPY

Initially, the paintings took their cues from my observations of tagging, vandalism and the power struggles associated with gang graffiti and visual strife but, as with a lot of my work recently, the paintings have become formal and abstract. I stopped thinking about them conceptually. I became hooked on the activity of painting. I think about the paintings in terms of space, depth, punctuation and color, which I suppose is similar to how artists have thought about paintings for centuries. I have become more comfortable with the idea that my context is already fixed, and to sit with something like a painting and to work through it only in terms of formalism is very liberating. I hole up in the painting studio and strip down the baggage.8

Ancient techniques, paradigms of the past, the search for a form—but a form is more than a relationship between materials. Ruby’s universe originates and grows out of textile artifacts, agricultural elements, scraps, bits of metal, and other recycled materials, and out of the multiplicity, the diversity, the analogy in which these things combine, for each cycle or series, in a sort of cyclopic cohesion. Their interaction creates a dynamic field, a correspondence of moving forces that encounter one another in the work and find an equilibrium there, up to the maximum degree of entropy. This is the famous dynamic field intuited with clairvoyance by the Futurists. Imagining a painting that, on the surface, reproduces a concept of pure abstraction, such as the dynamic essence of a body or of a machine in space; imagining the representation of a simultaneous action between an object and the environment: this is the Futurists’ true revolution. In a world in continual transformation, in the succession and interweaving of fleeting events, reality is no longer solely what it appears.

HEX/TURBINES

Entropy, concatenation, color, ecology, time, simultaneity, collage, assemblage, polymaterialism, lines of force, trajectory: a visual transposition of these terms coheres on the facade of the Palazzo Diedo, Venice, in the first act of a four-act project that Ruby is completing simultaneously with the restoration of the palazzo, the new headquarters of Berggruen Arts & Culture. A large-scale sculpture diagonally traverses five of the seven large windows on the top floor. A formal reference to the Futurist, Constructivist, and Suprematist avant-gardes is obvious here, as is the use of different materials and colors: the three primaries plus green, the complementary of red and the color resulting from the union of yellow and blue. The blades of what looks like the core of a piece of farm machinery are grafted onto an inclined supporting axis, forming a vector like the spine of a gigantic fish; toward the bottom, a yellow pennant counterbalances the large red disc oriented toward the sky. One can intuit the deep meaning of this installation in the stripping down of the image, powerful in the contrast of the two solid colors that pierce the unity of the facade. The work’s title, hex, falls between the explicit and the allusive, referring to the apotropaic talismans, propitious and auspicious, affixed to barns in the Pennsylvania Dutch community of Ruby’s childhood and adolescence. Hex signs are stars, often with sixteen points—an ambivalent number in its duality of the material and the spiritual. Both modes are inherent in Ruby’s thought, in a binary comparison where doubt drives every action and where the work assembles all antitheses within a superb complexity.

Like Balla’s Mercurio passa davanti al sole (Mercury passing before the sun, 1914), hex constructs an architecture of linear forces based on study of the universe of planets and constellations. It is as if the impulse to penetrate the secret of things were proportional to the search for the truth of creation: “The constellations have . . . a particular spirit that I find full of fascination and would like to express as best I can on the canvas. It is a difficult task, but there is too much poetry in the eternal passage of those worlds for an artist not to attempt it.”9 Just as Balla shifts the gaze from the elementary structures of vision to the principle of the dynamic universal form, Ruby, along the diagonal of hex, ignites abstract quantities of energy that spread out beyond the visual space. His response in four acts echoes the Futurist desire to reconstruct the universe into a reality that, now as then, shatters and fractures in a thousand directions.

It is also the prologue for the new series turbine. In these large-scale works on the wall, words enumerated above are articulated to an irregular and febrile beat, like a furious drumroll cutting across the bright space with the stridency of harsh and disharmonic colors. These alternate with quieter, apparently more intimate surfaces, such as a pink that brings to mind Si è rotto l’incanto. The term “synesthesia” must be added to all the others in the complex poetics of these paintings, whose unrestrained rhythm is accompanied by the roar of an internal clash—a deafening noise conveyed through onomatopoeic lines and colors, recalling a thunderous line in one of the Futurist manifestos: “All the colors of velocity and joy, of revelry, of the most fantastic carnival, of fireworks . . . colors in motion felt in time and not in space.”10

Among the euphoric notes in this clash that Ruby ignites, there emerges the odor of fire, iron, rust, laceration, battle, threat. Diagonals sometimes broken by straight lines evoke imaginary horizons to cut the surface into distinct and opposing fields. They are sometimes reunited at the center by a vertical that, as in Rorschach inkblots, marks an inverted and mirrored dichotomy, activating visual and psychological stimuli beyond the dynamic thrust already set in motion. Lines of force, forms of force, are mostly oriented downward, discharging the electric tension of the inner forces built on these assemblages of oil and cardboard on canvas. In turbine. gabapentin. (2022), meanwhile, they head upward, to detonate, in an almost geometrical partition, the magmatic energy ascending from the bottom of the abyss. The paint flakes off at the lines’ edges, like the fraying of a vision clinging tight to those lines of force that define the fixed coordinates of a cosmos of which we perceive only a blurry, partial image. The meter sets a relative tempo, a perspective to be repositioned and revitalized by the spinning and whirling rhythm of the indelible traces of history and memory.

1Nur Gueneli, a researcher at the ANU Research School of Earth Sciences, discovered the oldest pigment on Earth in the 1.1-billion-year-old marine sedimentary rocks of the Taoudeni basin in Mauritania. See Amy McKenna, “Ancient Chlorophyll Was Pretty in Pink,” National High Magnetic Field Laboratory, July 11, 2018. Available online at https://nationalmaglab.org/news-events/news/ancient-chlorophyll-was-pretty-in-pink/ (accessed January 23, 2023). Pink is also generated by the action of bacteria on algae in high-salinity environments such as the waters of the Great Salt Lake, Utah, a site of great inspiration for Robert Smithson and for his studies of the logarithmic curves of primordial geological elements for his Spiral Jetty (1970).

2Sterling Ruby, in Hili Perlson, “‘I Was Angry and I Sewed’: Sterling Ruby on How Growing Up in Small-Town America Drove Him to Make Art—and Break the Rules,” artnet news, April 29, 2022. Available online at https://news.artnet.com/art-world/sterling-ruby-sprueth-magers-berlin-2104855 (accessed January 23, 2023).

3Ruby, in “Sterling Ruby,” Alain Elkann Interviews, April 2, 2017. Available online at https://www.alainelkanninterviews.com/sterling-ruby/ (accessed January 23, 2023).

4Ibid.

5Leonardo of Pisa, known today as Fibonacci (c. 1170–c. 1242), devised the Fibonacci sequence, a series of whole numbers in which each number is the sum of the previous two. The result is a mathematical formula that tracks organic growth in nature. The formula had been codified as early as 200 bc by the Indian poet and mathematician Acharya Pingala.

6Zoe Leung, “Sterling Ruby Presents Thought-Provoking ‘Turbines’ Paintings at Gagosian New York,” HypeArt, November 13, 2022. Available online at https://hypebeast.com/2022/11/sterling-ruby-turbines-gagosian-new-york-exhibition (accessed January 23, 2023).

7Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, “The Futurist Manifesto,” 1909. Available online at https://arthistoryproject.com/artists/filippo-tommaso-marinetti/the-futurist-manifesto/ (accessed January 24, 2023).

8Ruby, quoted in Jérôme Sans, “Schizophrenic Monuments,” L’Officiel Art, no. 5 (March–May 2013): p. 277.

9Giacomo Balla, in L’Alfiere 2, no. 25 (January 24, 1911), in Balla, Scritti futuristi, ed. Giovanni Lista (Milan: Abscondita, 2010), p. 194.

10 Carlo D. Carrà, La pittura dei suoni, rumori e odori, manifesto, August 11, 1913. Available online at https://www.google.com/books/edition/Lacerba/CYJFAQAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=tutti+i+colori+della+velocità+e+della+gioia,+della+baldoria,+del+carnevale+più+fantastico,+dei+fuochi+di+artifizio+(…)+colori+in+movimento+sentiti+nel+tempo+e+non+nello+spazio&pg=PA186&printsec=frontcover (accessed January 24, 2023).

Translated from Italian by Marguerite Shore.

Sterling Ruby: TURBINES, Gagosian, West 21st Street, New York, November 10–December 23, 2022

Artwork © Sterling Ruby