Marissa Del Toro is an independent curator and art historian of contemporary and modern art of the Americas (primarily Latin America and the United States). Currently based in New York, she was a 2021–22 curatorial fellow at NXTVHN in New Haven, Connecticut. In both her professional and her personal life, she continues to work for the promotion and advocacy of diverse narratives in art.

Jamillah Hinson is an independent curator and arts programmer. With a focus on historical and contemporary Black cultural and artistic traditions as they present themselves through experimental sound, film and photography, and performance, her practice engages various methods of storytelling and centers artistic and community narratives.

Ashley Stewart Rödder joined Gagosian as a director in 2019 and is based in New York. She works with a number of the gallery’s artists, including Nathaniel Mary Quinn, Titus Kaphar, and Stanley Whitney. She was previously the director of sales at Salon 94, where she oversaw the sales team and worked directly with a number of artists.

As a graduate student at Yale University in early 2006, Titus Kaphar began imagining a way to support artistic and economic development in the Dixwell neighborhood of New Haven, Connecticut. This once burgeoning and diverse working class community had gone on a decline in the face of the economic challenges now common in postindustrial regions, made worse by policies and attitudes of past decades that worked to perpetuate inequality. Dixwell had become a disadvantaged, predominantly African-American neighborhood, standing in stark relief to its gilded university neighbor.

Over a decade later, in 2018, Kaphar cofounded the non-profit community arts hub NXTHVN in collaboration with Jason Price, the name referencing its home in New Haven as well as the goal of being the “next haven” for artists to cultivate their practices and careers. In the years since, the project has grown steadily, affording young, underrepresented artists and curators opportunities and the community a core on which to build. Among its initiatives, NXTHVN employs local high school students as paid apprentices; during the pandemic, the center hosted pop-up vaccine clinics and helped organize a food drive to collect groceries for local families. Much like Kaphar’s art practice, NXTHVN’s programs and exhibitions generate conversations that confront injustice, reveal hidden narratives, and shift perspectives. The ever-open doors and cross-sector collaborations demonstrate art’s vital social role.

Kaphar and Price, together with Deborah Berke, dean of the Yale School of Architecture, drew from Dixwell’s history to breathe new life into NXTHVN's built environment. The tailored architecture of the NXTHVN building—full of individual studios, gathering spaces, a black-box theatre, and a forthcoming library—fosters creative work and community-building.

NXTHVN’s program of yearlong fellowships provides dedicated workspace, rigorous critique, and professional development workshops for early-career artists and curators. Its unique curriculum emphasizes intergenerational mentorship, practical business and career skills, and cross-sector collaborations. Fellows work closely with the local high school apprentices to ensure that the next generation of regional talent is given a chance to excel in the fine arts. Offering what many of the country’s underfunded public schools cannot, NXTHVN provides local students with paid opportunities to learn from and work with contemporary artists.

In the following pages, the most recent curatorial fellows, Jamillah Hinson and Marissa Del Toro, address their curatorial praxes. In her essay, Hinson engages with the work of several artists working through the complexities and challenges of a topic that informs her curatorial mission: the archive. Del Toro meanwhile reflects on the evolution of her thinking around notions of care and community, directly addressing her time at NXTHVN.

Ashley Stewart

MARISSA DEL TORO

Driving the winding roads from Connecticut to New York in the fall of 2021, all I could focus on was the lushness of the reds and oranges in the woods that lined my path from New Haven to the Hudson Valley. Having lived on the West Coast and in the Southwest most of my life, dramatic changes of season were new and marvelous to me. Making my way through the curvaceous roads of the valley and along the riverways, I also thought about the work of Emilio Rojas, an artist and visiting lecturer at Bard College to whom I was making a studio visit that beautiful day, and about his use of nature and natural spaces to deconstruct traumas and create pathways for decolonization. Later, over a meal of handmade tortillas, arroz, and pollo guisado, I got to know more about his practice. Besides comforting my nostalgia for my home and family in California, sharing that meal with Rojas was a moment of exchange and discussion, providing me with a sense of community and engagement that I had been missing since moving to the East Coast.

I had arrived at NXTHVN as a curatorial fellow in July of that year. I didn’t know what to expect: after months of the COVID-centered reality of Zoom worlds and TikTok videos, I had just moved across the country from California to live and work in the Dixwell neighborhood of New Haven. As a curator and former museum worker, I had witnessed and experienced what Dr. Kelli Morgan, curator and inaugural director of curatorial studies at Tufts University, calls the “nefarious culture of white supremacy” in American art museums.1 So I came to NXTHVN as already an advocate for change, and as what curator and art historian Maura Reilly describes as a “curatorial activist.”2

In addition to NXTHVN, I also worked, and continue to work, as codirector of research for Museums Moving Forward (MMF), “a data-driven initiative to support greater equity and accountability in art museum workplaces through coalition-building, research, and advocacy.”3 Much of my work entailed researching the front-facing aspects of museums, specifically data on exhibitions and collections, which many know have predominantly favored white male artists. Even though much of MMF’s work is focused on data research, we are also active in building relationships with other groups and key stakeholders as a way toward establishing equitable and accountable practices in museums. Collectivity and coalition-building have been heavy themes in my career, and this was part of the reason I was excited to be at NXTHVN. My goal for my year there was to give myself the time and space to contemplate my curatorial praxis—to look at the movements of curating and how it is enacted. I was especially interested in its power as a process that can potentially create degrees of change. In retrospect, I did learn more about my curatorial practice while at NXTHVN, and about myself as well, in addition to cultivating a greater sense of the kind of support that artists need as they navigate and work in the art world.

When Titus Kaphar, MacArthur-winning contemporary artist and cofounder of NXTHVN, first met with us at the beginning of our fellowship year, in August 2021, he emphasized that the coming year was going to be a whirlwind but also a pivotal moment for all nine fellows. In this moment, he noted, we were now part of each other’s networks. We in the third year of the fellowship, Cohort 03—Layo Bright, John Guzman, Jamillah Hinson, Alyssa Klauer, Africanus Okokon, Patrick Quarm, Daniel Ramos, and Warith Taha—began the fellowship as strangers coming from all walks of life and levels of experience, but once we began the seminar discussions, we started to realize some of our commonalities and shared understandings. Over time, as we spent more time working alongside each other and living in the same apartment building, we became more than a professional network; we became mutual supporters and friends. I will note that we did not always agree with each other or see each other’s perspective as clearly as we would have liked, but we did for the most part accept one another, even in our disagreements, and as we shared our experiences and at times the grievances that we’d encountered in our respective careers, we developed a strong sense of trust. We offered each other a safe space as we spoke on our realities, some of which were hard to hear, and we suggested strategies for each other on how best to navigate and maneuver the grittier parts of the art world. Through these discussions I also began to learn more about the type of care artists need and what I can offer them as a curator. Patience is necessary in any professional environment, but I believe that artists are especially in need of it. There is often a hustle and sense of urgency in the art world that puts undue pressure on people and can lead to less-than-ideal work. Creatives need the space and time to feel, create, and think—which is part of what NXTHVN offers.

Beyond our professional discussions and seminars, we came together as a community. All but one of us were new to New Haven, and we arrived amid a pandemic. We moved carefully for our own safety and the safety of others. In the fall, we began holding small dinner parties at each other’s apartments. These social events gave us all a chance to relax and to separate ourselves temporarily from studio and curatorial work. When the snow arrived—a first for a few of us—we began to gather around the warmth of homemade stews, such as Hungarian goulash. The aroma of paprika joined us as we ate, warming our cold hands on our bowls before returning home in the cold weather or starting a late-night snowball fight during one of Connecticut’s first blizzards of 2022. These collective moments allowed us to let our guards down and just hang out.

Additionally, as I cocurated with my fellow curatorial fellow Jamillah, we managed to merge our distinct curatorial styles into two engaging exhibitions. The first we coorganized was Let Them Roam Freely, at the NXTHVN gallery, where we commissioned the artists Hong Hong and Darryl DeAngelo Terrell to create new works. Using performance-based methods of physical movement, Hong and Terrell developed works in relation to the idea of the portal, Hong a large-scale painting on paper, Terrell photography and sound. It was the first time either Jamillah or I had commissioned artists, so we learned and experienced quite a bit through this show. For myself, I learned that projects like this one require a collaborative mutual guidance between artists and curators, as well as a flexible understanding that not everything will go as expected. When one of the artists turned out to have forgotten a key piece of equipment, for example, the result was a four-hour-round-trip Sunday drive to New York for a replacement. The success of our mission was celebrated in a deli over one of New York’s finest slices of pizza, where we laughed over how lucky we had been to make it to the city before the store closed. That melted cheese was a much-appreciated reward for our unexpected journey, though not as much as seeing the work beautifully finished and installed in the gallery.

At NXTHVN, I learned more in depth about what care looks and feels like in curatorial work. Even though I arrived with a strong background and experience, I was able to learn and develop my practice. I came away from my year there with a greater sense of how better to support artists and creatives, as well as how to best to use my position as a curator.

JAMILLAH HINSON

Brought up in a living archive masquerading as a house, I was unknowingly immersed in cultural and art-historical information. My earliest encounters with record-keeping were familial and communal, being largely based on storytelling and oral histories. Eventually I became fascinated with non-Western archival traditions, and with experimental and nonarticulate forms of archiving. As I moved farther into my practice, both professionally and conceptually, I developed an aversion to the traditional Western archive. The importance placed on institutional archives, and on their standards of useful information, made less and less sense.

“The traditional Western archive,” in my thinking, refers to the amassed material and information, visual and linguistic, held in many cultural institutions, as well as to the conceptual meaning behind the existence of these collections and the histories of how they came together. When looking at these archives, we must understand the trauma stored in the collection and in its use. We cannot remove from it its concept and action—its compression of the lives of Black and Indigenous, marginalized and gender-expansive and disabled people into data.

To seek other forms of record in place of those traditional archives that historically have both erased and enacted violence on Black and Indigenous people and communities is to admit the shortcomings of a stagnant archive. To recognize the place of ambiguity and ephemerality in record-keeping and documentation is to allow for a kind of softening of the metaphorical barriers into and out of the archive. This in turn allows for the introduction of experimental documentation into an art practice, through process, material, or the artist’s own personal and practice archives.

Pushing against norms of documentation to break apart the archive and the acceptance of its conceptual and material presence and history, artists Sadie Barnette, Tsedaye Makonnen, AJ McClenon, and Alisha B. Wormsley consider their humanity, Blackness, and presence. The conventional archive, the art world, and the West are spaces in which Blackness is not afforded normalcy, and normalcy is inherently linked to humanity and autonomy. Why should one be indebted to protocols that determine an archive in which one is terrorized?

The archive tends to be viewed as an infallible tool of human record-keeping, dependable beyond fault or misinterpretation. Yet ambiguity and ephemerality are very much settled in the archive, which today is being disrupted more often and with more nuance. Whether visual or linguistic, archives are increasingly being used as starting points for their own deconstruction.

In the book Black Women as/and the Living Archive, Makonnen compiled years of interwoven text threads, emails, design decks, Zoom screenshots, camera-roll footage, and images of Black family homes, altars, and pets. The collection is fuller and more humane than historical and contemporary record-keeping allows the traditional Western archive to be when it comes to Black people in the Americas. Unlike records of “commodities,” or data systems articulating likelihood of death, Makonnen’s archive breathes life into those it documents.

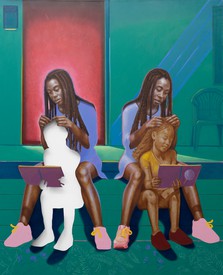

Existing as a chronicle of the larger Black Women as/and the Living Archive curatorial project, as well as of the histories that brought its participants together—beautifully articulated through a foldout “Relational Connection” map webbing the lives of eight women over the last twenty years—Makonnen’s book amalgamates the information she deems necessary to bring the viewer on a pilgrimage tracing her journey while leaving room for individual interpretations of her work. A centerpiece of Black Women as/and the Living Archive is Wormsley’s film Children of nan: Mothership (2020). Widely known for her serial billboard project There Are Black People in the Future (2017–20), Wormsley uses a historical and anthropological narrative throughout her practice to tell metaphorical stories about Black women’s power and survival, and ultimately about our search for and discovery of ourselves through the archive. Wormsley’s practice utilizes the power of simply making it so, demanding space and presence.

Cementing a place in the future means affirming your autonomy in the present while seeking and protecting those in the past. Following the interdisciplinary and nondisciplinary practices of their predecessors, artists are expressing autonomy through destruction, remembrance, and physical assertion of themselves into the record, dissolving the purported permanency and authority of the archive.

With the placing of her hand into an image of a family photograph or a surreal re-creation of the Black family and Black communal spaces, Barnette introduces ephemerality and movement into multiple interlocking archives: archives of her family, archives of San Francisco’s cultures and pasts, and the political record. Her installations pull memories, specific eras, and bygone spaces back into a physical world, recontextualizing Black and queer histories, among others, as this newly created space merges with the original. In The New Eagle Creek Saloon (2019) she accesses past, present, and future by mining the installation’s namesake, the New Eagle Creek Saloon in San Francisco, opened in 1990 by her father, Compton Black Panther Party founder Rodney Barnette, as the first Black-owned gay bar in the city. In Sadie Barnette’s re-creation of the saloon, a stylized Eagle Creek sign, glowing in pink neon, perches on a bookshelf that flows into a translucent pink-topped holographic bar. Beneath the bartop, faces peer back at the viewer, in photographs snapped in the original establishment. Crushed beer cans and glitter-coated telephones are nestled into the body of the bar, overlapping primary and re-created ephemera. Glittering speakers and couches upholstered in holographs are washed in pink and purple light in an otherwise blank space. Barnette conceives of a space where the idea of the archive, particularly archives of queerness and nightlife, is flattened in time but enlivened through physical presence.

The current emergence of interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary artists may correlate to the interest in the archive, and the disturbance and reimagining of it, as a center or by-product of contemporary practices. Columbia University professor Saidiya Hartman’s idea of “critical fabulation”—the reimagining of the archive to give humanity and identity to those whose lives have become data points within it, introduced in her essay “Venus in Two Acts” (2008)—is crucial as we deconstruct and refashion the archive’s limits and powers. Critical fabulation, antiarticulation, general fracturing—these tools can be used to create anarchy in the traditional archive without centering it in practice. The focus on experimental and nontraditional record-keeping passively deconstructs the traditional archive, removing direct labor from the artists. Which is not to say that the labor that scholars such as Hartman are dedicating to freeing those narratives directly is to go unnoticed. Nonlinear narration is not a modern convention; it’s an intuitive way of storytelling and presenting facts that when used in film or literature mimics the elusiveness of memory. Using the body to archive experience is far from new to storytellers; like nonlinear narration, it doesn’t rely on rigid structures to tell a story or communicate information.

In their 2019 performance series Dark Water: Polarity, Sharks, Adolescence, and Being the Darkest Girl in the Pool, McClenon examines the historical and political relationships surrounding Black Americans in relation to bodies of water. Employing experimental sound and performance, McClenon demonstrates the strength of presenting archival material in an alternative way. Merging theater, modern dance, and storytelling with cultural and historical research, they reimagine and release the stories of others in tandem with their own and that of their community. Through their performance, McClenon effortlessly offers the audience a deep understanding of the relationships they examine. Using languid yet entrancing movements, they recall traumas they didn’t witness but inherited while simultaneously enacting joyous motions of Black leisure along the water. Just as in Makonnen’s and Wormsley’s practices, McClenon’s series is steeped with information that refuses clarity.

As these artists turn to questioning and re-creating, a sense of anarchy emerges in their practices around information. The heritage they draw from Black cultural traditions makes the destruction of enforced social hierarchies wonderfully possible. Countering the idea that theoretical or academic work is the only appropriate intellectual or creative framework in which to analyze data, the acts of record-keeping and documentation, in this context, don’t concern themselves with summarization.

The new structures being built and collapsed and reworked and celebrated in the processes and practices of these artists are both singular and collective. Whether or not they resemble each other, they cannot exist without one another. Shifting and blurring as needed, object, documentation, body movement, and story repeat and repeat themselves until the details adjust to accommodate what must be heard and remembered. Sharing stories and blending newly realized archives is a radical example of creation, inserting the self and others into time and giving new existence to those the traditional archive silences.

1Kelli Morgan, “To Bear Witness: Real Talk about White Supremacy in Art Museums Today,” Burnaway, June 24, 2020. Available online at https://burnaway.org/magazine/to-bear-witness/ (accessed August 25, 2022).

2See Maura Reilly, Curatorial Activism: Towards an Ethics of Curating (London: Thames & Hudson, 2018).

3Museums Moving Forward website, online at https://museumsmovingforward.com/ (accessed August 25, 2022).