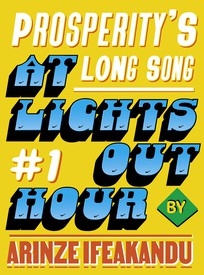

Emma Cline is the author of The Girls (2016) and of the story collection Daddy (2020). Cline was the winner of the Plimpton Prize and was named one of Granta’s Best Young American Novelists. The Girls was an international bestseller and was a finalist for a National Book Critics Circle Award, the First Novel Prize, and the Los Angeles Times Book Prize.

Percival Everett is the author of twenty-two novels and four collections of stories. His novels include The Trees (2021), Telephone (2020), So Much Blue (2017), and Erasure (2001). He has received awards from the Guggenheim Foundation and Creative Capital. He lives in Los Angeles, where he is distinguished professor of English at the University of Southern California.

Brandon Taylor is the author of the novel Real Life (2020) and the collection Filthy Animals (2021). His work has appeared in The New Yorker, The New York Times, Vulture, The Cut, and elsewhere.

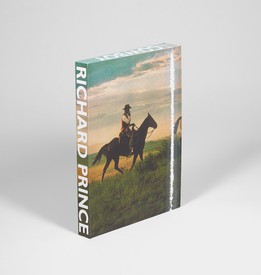

Percival Everett is a trickster, his writing always shifting and twisting in dazzling and surprising ways, his books dancing a two-step with the reader. In his novella Grand Canyon, Inc., published by Gagosian’s Picture Books imprint, he takes us on a bawdy trip through the American West via the larger-than-life character of Rhino Tanner. Grand Canyon, Inc. is presented alongside work by Richard Prince, another of our great tricksters. Both Everett and Prince subvert the iconography of the West, interrogating its mythic visual and narrative tropes with a canny sideways view. The pairing of their work is especially resonant.

Brandon Taylor, whose novel Real Life was short-listed for the Booker Prize of 2020, wrote the introduction for last year’s reissue of Everett’s canonical novel Erasure (2001). Here Taylor speaks with Everett about Grand Canyon, Inc., self-mythologies, and the American fantasy of the western.

—Emma Cline

Brandon TaylorI’m so glad we get to talk.

Percival EverettYes, what a pleasure. First, thanks for writing the introduction to the reissue of my book Erasure, that was great.

BTOh, I’m thrilled. It was nerve-wracking to write about that book; it’s so important. And I’m equally thrilled to be speaking with you about the novella Grand Canyon, Inc. What a wild and wacky ride it is [laughs].

PEI’m glad you like it.

BTMy first question is about the origins. What possessed you to write about this character Mr. Rhino?

PEWell, you know, he’s so American. I think that was the first part of it. I’ve spent a lot of time in the Grand Canyon, and I watched over the years as the area deteriorated and the infrastructure of the parks system in general fell away. I imagined what the government might do to keep it open. And that’s where it started.

BTThere’s a dark exuberance to the book, this sort of gleeful rollicking absurdity that you bring to almost every one of your stories. But here, the extreme Americanness of this particular setup really stood out to me. It’s funny and absurd at times, but the more you think about it, the more you realize, Yeah, that would happen, the American government would sell the rights to the Grand Canyon. And of course the very next thing that a person does after buying it is plop this monstrous gift shop theme park on it. How did those different threads—national landmarks, public lands, this very American impulse to turn everything into money—come together for you?

PEI think it probably started when I was thinking about the privatization of prisons. My first idea was not the Grand Canyon; my first idea—and I even remember its title, Cottage Industry—was a world in which private citizens are able to take in prisoners because the prison system is overcrowded. And as the system is privatized, actual families have to show that they have a cell in their houses and take in a prisoner who then works for them. It’s a little bit like the Stanford prison experiment [1971], where no matter how nice the people are, they still become abusive to the people they’re holding prisoner. That was the thinking that led to Grand Canyon.

BTI’d love to hear you talk a little about how you approach things that seem absurd on their face and then make them feel totally natural in the context of the story.

PEI have to start by saying it doesn’t always work. So I have to back up. As with most strange things, the more matter-of-fact the presentation, the more believable they are. If no one in that world thinks they’re strange, then they’re not. Therefore, I usually try to go with understatement. Understatement in fiction leads to overstatement in reality [laughs].

BTAnd with the protagonist of this story, you’re able to approach something akin to the idea of “the man, the myth, the legend.” Rhino Tanner is this outsized character when we meet him, and then, in the course of the book, you include these quieter moments of his childhood. There’s a vulnerability to him in his youth that you don’t quite see when he becomes the Rhino Tanner. How did you go about finding the squishy human [laughs] inside someone that legendary?

PEWell, I think at some point all of us are squishy humans. No kid starts out bad. I’m not even sure I was trying to be fair to him as much as . . . if he’d started out bad, he wouldn’t be nearly as interesting as he is. It’s the insecurities that drive that manic desire for power and wealth and fame. Again, it’s this very American experience. You know, think of all the kids who’ve gone off to war for this country with no choice but to follow orders, and of the mythology that surrounds all of it, the idea of masculinity that comes out of films of the West and of war.

BTAbsolutely. Rhino makes his fortune killing endangered animals; there’s that incredible scene where he and the sultan are in the balloon and they drop grenades on giraffes and water buffalo. It’s total carnage, but he’s like, Yeah, another day on the job.

How did you decide to have Rhino’s sidekick Simpson Trane, aka BB, narrate the novella?

PEI couldn’t really achieve Rhino’s voice, and I realized I needed someone else to tell this story. And by having it in BB’s voice, while it’s effectively written in the third person, I could editorialize without intrusion.

BTI love that moment when he reveals himself as the narrator and you get a little bit of his story, too. You start to realize, Oh, that poor little sidekick is actually acting with agency within that larger man’s narrative. He’s a fascinating character, BB, because he’s pulling the strings in a certain secret way.

PEWhoever tells the story is pulling the strings. Which is the thing about history: the victor writes the history and it becomes truth.

BTYeah. That makes me wonder about fiction as a space to take on some of the larger questions and contradictions of history. Every time I read one of your books, there’s always a part that engages with history. What does it mean to bring history into fiction, and how do you use fiction to talk about history?

PEThat’s a big question, Brandon, and I’m not sure I’m smart enough to answer it [laughter]. Basically, I just trip over it. It’s always in the room and it’s hard to avoid it, given that basically we’re all horses [laughs]. I used to train horses and mules. I love mules because they’re really smart, but what we used to say about horses was, That’s just a thousand pounds of dumb muscle. The difference between the two is, if you have a two-acre pasture and there’s one nail out in that pasture, the horse will find that nail and throw himself on it repeatedly. And that’s essentially what we writers do: if there’s trouble in the room, we will find it.

BTOh, that’s my life that you’ve just described so succinctly. I feel like I’ll never recover [laughter]. And I do feel like Rhino Tanner is throwing himself on some of the great nails of American history, right? There is the West, for which he seems to be a bit of an avatar in its various beauties and troubles. There’s alertness, grandness, and natural beauty there, but then there’s also the injustice of American Manifest Destiny and all the horrible things it portends. The West looms large over your work—as a site of imagination and inquiry and plot, but also as a source of a lot of America’s ideas about itself.

PEFirst of all, there’s the real West and then there’s the western. What I love about the real West is, first, it’s sparsely populated. What you get in sparsely populated areas is a weird mix of self-sufficiency and interdependence. Nobody’s going to survive out here alone, but people come here to be alone. What that gives birth to is this weird idea of individualism; everyone wants to underscore the self-sufficiency part. And so the hero of the western, the one in the movies and in pulp fiction, is the character who doesn’t need anyone and knows everything. And that’s how America would like to see itself.

BTIt’s a very romantic genre.

PEIt is.

BTAnd in some ways it descends from the Romantics, like Longfellow, no?

PEAbsolutely, and even further, from the Greeks.

BTYes.

PEAnd they’re complete fantasies, fantasies that become more absurd than anything I’ve ever written. There’s a film called The Unforgiven [1960] that’s about American racism. If you haven’t seen it, I encourage you to watch it, for no other reason except Audrey Hepburn’s supposed to be a native person.

BTOh no.

PEYes. But the film addresses racism head on, despite these absurd things that you’ll see in it about the depiction of Hepburn as native and the dismissing of the lives of all these Indians who of course get shot off horses and all. But in general, the movie’s trying to deal with big issues, and that’s what starts happening in the 1960s, after the heyday of the westerns: America starts to try to deal with itself, with racism, and with the war in Vietnam. All sorts of things come into it as a genre, and it shifts.

BTI feel like those impulses are also present in this novella, in that it talks about war, it talks about capitalism, and it talks about climate change. It addresses natural disasters, the government’s inadequacy in the face of its citizens’ needs, and it also, in an incredible way, talks about the mob. And even beyond all of that, there’s this incredible thing where this Japanese family enters witness protection and takes on these very seemingly white names, and then there’s a group of white people who go into witness protection and take on Korean names. There’s a moment of something like a racial uncanny happening. I was like, How can he do this? How can he create this mélange of genres and just keep going like nothing at all is happening [laughs]?

PEI’ve always been fascinated by witness protection and I’ve always wondered what it would be like if an entire community were in the program. No one can say they’re in witness protection but everyone is in witness protection—they’re all pretending.

BTThat feels like one of the quieter but very present themes of the novella: identity, and the fungibility of identity, the collectively decided terms of identity. That’s something that I feel a lot of fiction tries to take on in really unsubtle ways and this novella does in a really swift, concise way.

PEIt’s a kind of complicated passing story.

BTYeah, the racial uncanny of passing. And in some ways I feel like even Rhino Tanner’s identity undergoes some shifts and changes in perspective.

I don’t take my political concerns, and the philosophical ideas I’m trying to address, to work with me. I trust that those things have either been worked out or are working themselves out, so when I go to work, I’m simply trying to serve the story.

Percival Everett

PEWell, he’s that western hero that can’t exist, so he’s constantly constructing his own identity. And that’s this American thing of how can there be a Rhino Tanner—forgive me for saying the name, but how can there actually be a Donald Trump? You know, if I wrote a character as ridiculous as that, no one would believe it. But America can produce one.

BTWith shocking regularity; there are five on the news every day, it feels like. But you know, as depressing as that is, you’re so good at capturing what’s funny about it. There’s just something intrinsically funny about this dorky kid who grows up to be this self-mythologizing man who shoots all these animals and thinks he’s doing something good, and then uses the money he makes to buy a national landmark. And you know, the impulse is to say, Well, of course it’s insane that anyone could own a national landmark. But it’s also kind of insane that the American government can just decide that it owns land. And in some sense the real absurdity is that that land was stolen anyway [laughs].

PEOr, speaking of absurdity, think about January 6—

BTOh my gosh. I mean, again, a thing that seems utterly ridiculous. If you were to pull a person from 2012 and tell them that on January 6, 2021, people are going to storm the US Capitol, they’d be like, No, this isn’t Napoleonic France. This isn’t England circa the 1600s. We don’t do that.

PEAnd then you say, Wait, let me describe these people to you. There’ll be a guy wearing horns.

BTThe QAnon vegan shaman. If a person wrote a novel about the events of that day ten years ago and tried to publish it, they would have been laughed out of every publishing house.

PEAnd it’s a place for fiction to predict in some way the extremes to which we will go. I think of Sinclair Lewis’s novel It Can’t Happen Here [1935], which tells us that January 6 was going to happen.

BTIn times that feel as extreme as these, I wonder how fiction gets its arms around the times, as it were?

PEThat’s the challenge. And you’re a young man, so it’s up to you [laughs]. I give up.

BTBut when you were writing it, did it feel like the world was too absurd for you to even come close to, or were you just focused on telling the story?

PEI don’t take my political concerns, and the philosophical ideas I’m trying to address, to work with me. I trust that those things have either been worked out or are working themselves out, so when I go to work, I’m simply trying to serve the story. Also, you know, I’ve chosen to write fiction to make a living, which is ample evidence that I’m mentally deficient. No one needs to hear my opinion or my message about anything. So I leave behind all that stuff, and I just create the world.

BTYeah. I feel like that’s the way it’s got to be; it seems too impossible otherwise [laughs]. I have no idea how the muckrakers did it—you know, back in the day, writing those novels that were so, quote/unquote, “socially engaged.” And I’m just like, I have no idea, guys, how to turn political thoughts into fiction.

PEThat’s why we don’t read those novels anymore [laughs].

BTIn his book On Native Grounds [1942], Alfred Kazin says that the socialists didn’t have novels, they had pamphlets. But there’s a kind of political fiction that calcifies really quickly, because it’s so concerned with re-creating the fact and detail that it loses sight of the moving human components.

PEAre you familiar with William Melvin Kelley’s dem [1967]?

BTNo.

PEYou’d love it. It’s one of the stranger political novels in that the bones of it aren’t political at all. The bones of it are human and the flesh of it is political.

BTI’ve got to read it. I love Ann Petry’s The Street [1946] for that reason.

PEOh, great novel.

BTThat novel is so much about a woman just trying to make it, and she’s trying so hard. And I used to not understand that—I used to think, These writers say they’re not political but how can they not be, there are obviously political resonances here, I don’t understand. But now, older and maybe a little wiser, I’m like, Oh yeah, you’re just trying to tell a story and if you’re engaged in the human context, in the human circumstances, in the characters’ social reality, all that stuff, what you think about it finds its way in, hopefully.

PEYou can’t hide from yourself. I tell my students this all the time. I give them a challenge: I say, Write down your five most profound fears, death not included. Then give me a real story. If I can’t find every one of those fears in what you’ve given me, you get an A for the semester. And they’re going to work so hard trying to make their story that they’re going to do what I want them to do anyway.

BTMy writing teacher, Ayana Mathis, said something similar: you’re never going to betray your sensibility. No matter how hard you try to write away from yourself, you’re never going to betray what you hold fundamentally core to yourself. You’re just never going to get far enough away in order to be able to.

PEThat’s right. In grad school I had classmates who would say, To pay the bills, I’m going to write a romance novel. And I said, Do you read romance novels [laughs]? Well, then you can’t make one. If I tried to write a romance novel, I know I can put sentences together, but ten pages in, everyone would realize I was making fun of it. And there’s nothing I can do to stop that.

BTThat reminds me: one thing I value about your stories is that I never feel like you’re making fun of your characters. Sometimes you’re laughing with them, perhaps, but you’re never making light of them.

PENot in the most recent novel. I don’t know if you’ve read my novel The Trees [2021] yet, but I’m sorry, I’m not very fair to white people [laughs].

BTI haven’t read it yet, but all of my friends who have read it love it and are like, He’s never been better. It’s doing the Instagram rounds, it’s resonating.

PEWell, speaking of that, I have to tell you, [the novelist] Danzy [Senna] doesn’t do any social media, and I don’t know where it is she follows you, but she’s a fan of yours. She gave me Real Life to read. I enjoyed it very much. I was really taken with it. And I don’t read novels often.

BTOh, amazing. I’m really honored. Writing that novel was a strange experience. I’m not sure how I did it. Maybe all novel writing is like that.

PEWas that your first novel?

BTYes.

PEAll right, well, I officially hate you.

BT[laughs] I mean—

PEThat’s a nice way to start. That’s great.

BTYeah. I wrote it while doing science work all the time and—

PEWhat kind of science?

BTI was in a research lab. I was studying stem cells and nematodes and I was working at UW Madison. I was in a PhD program in biochem.

PEThat was one of my undergraduate majors. So you were a wet-bench chemist?

BTI was.

PEWow. You don’t find too many wet-bench chemists anymore.

BTNo. Increasingly the dry lab is taking over. And something I found really fascinating while working in research was the growing schism between dry bench and wet bench. The culture war was really heating up.

PEReally?

BTYes. I think in the next four to five years especially, it’s going to become a thing that people who aren’t in science know about, this schism between wet and dry bench [laughs].

PEYou’ve got to write this right away [laughter]. I did summer work for an entomologist as an undergraduate, isolating and synthesizing the trail pheromone of a certain ant. It was the most boring job I’ve ever had, crushing ants and doing gas chromatographs of what was there and then trying to make these things—

BTThe mundane aspect of work. Very exciting.

PEBut without that stuff I wouldn’t be a writer now.

BTHow so? Because I feel similarly, but other people often look at me like I’m nuts when I say it.

PEI think it generates a certain attention to detail. And being comfortable with the scientific method is a good way of proceeding with a story, explaining why I’m interested in it and what I hope to do with it. Not that stories ever do what you think they’re going to do, nor should they. But it’s a way to springboard into it.

BTI totally agree. I always feel like science and writing are so similar. Even the process feels similar, because it’s you and this . . . thing for many months and years, and you have no idea if it’s going to work, and if it doesn’t work you don’t know if it’s you or if it’s the thing or if some other random thing has interceded. The lines of inquiry feel quite similar.

PEYou’re trying to piece together a world that makes sense. And it really has nothing to do with reality.

BTUltimately, what you’re trying to do in science and in fiction is to see some alternate version of the world.

PEYou’re trying to have it make sense.

BTTrying to reconcile the irreconcilable. So great! You’re like the first other scientist who is also a writer that I’ve ever spoken to, and I feel—

PEI’m hardly a scientist [laughs].

BTDoing gas chromatographs on ant pheromones? Hard to get more science-y than that [laughter].

PEAs one nerd to another [laughter].

BTAmazing. Oh my gosh. I think we have to end on that, right? One nerd to another.

Percival Everett's Grand Canyon Inc. was published by Gagosian in 2021