If you could go back and do it all over again, would you? I don’t mean this in a morbid way—not as some sort of deathbed regret counterfactual. What I mean is: Did you have a good time? Did you enjoy the experience? Would you get back in line for the roller-coaster ride? Nostalgia has gotten a bad rap in the twenty-first century. It’s written off as escapist at best, crypto-fascist at worst—a sickness of the soul for those too cowardly or uncreative to face the future. This diagnosis correctly identifies the political implications of nostalgia for sure, but it misses the personal, cultural, and intellectual aspects of nostalgia that make it the trend that keeps on trending.

The nostalgic overtones within Alex Israel’s work are hard to miss. Alex embraces the scenic sweep of the California lifestyle, the Hollywood studio system, West Coast bobo consumerism. The Golden State’s beachy teen hedonism is impossible to disentangle from the Pacific. It’s a media relic of The Endless Summer (1965)—a documentary that follows a pair of SoCal surfers in search of the perfect wave (a constant motif in Alex’s work). Not coincidentally, the film also inspired the name of a group show that Alex curated in 2008. The neon, sunglasses-at-night alienation of the Hollywood Hills that comes with being too close to the image factory is refracted in Israel’s collaboration with the Brat Pack author Bret Easton Ellis, a writer of autofiction before we called it such, who popularized teenage cokehead degeneracy under that most Californian of presidents, Ronald Reagan. Alex encodes the duality of Los Angeles in his work: its hot smoggy days, its cold desert nights, its promises; and its lies . . .

Alex understands his hometown the same way the film-critic-slash-filmmaker Thom Andersen understands LA. In Anderson’s video essay Los Angeles Plays Itself (2003), he points out that the city is a stage for the entertainment industry. Always dressed up as somewhere else, Los Angeles becomes ubiquitous yet invisible. What Americans think of as New York is more often than not downtown Los Angeles. What Americans think of as Stars Hollow, Connecticut, is the Warner Bros. lot in Burbank. This gives the cityscape its uncanny quality as it re-renders itself for daily life after the director yells “Cut!”

That was my experience one sunny February day, visiting Alex at Warner Bros. One minute the Mystery Machine is careening by while a tour guide rasps over a PA system. The next I am confronted with the iconic gazebo from Gilmore Girls (2000–07). It looks all right. It looks all wrong. I remember watching the show as a teenager in Upstate New York, thinking the hillside at the edge of the town commons seemed topographically incongruous for Connecticut (and somehow always escaped snow). Now it all made sense. There aren’t mountains in southern New England. There aren’t blizzards in the sprawl of the San Fernando Valley. The common complaint from European friends about Los Angeles is that it’s not a city, it’s a giant suburb. This is incorrect. Los Angeles isn’t a city because it’s a Dream Factory. It constructed the American Dream, the California Dream, and of course the Teenage Dream. This is where Alex Israel chooses to fabricate his art. Not in an atelier, but in one of the Dream Factory’s premier production modules.

Alex wants to show me a new piece he’s working on in the scenic painting department. The picture is large: a forest populated by cartoon woodland creatures. Stylistically it’s reminiscent of Walt Disney’s earliest feature-length production, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937). Like many of Alex’s paintings, the panel is shaped like his profile. In the image, Alex sits among the critters, a cartoon version of himself, perusing art history tomes in an idyllic deciduous grove. Alex tells me that he’s one of the last clients employing the scenic painting department. (He is now its largest customer, employing its painters 360 days a year.) Most of the employees were long ago replaced by green screens and an obscenely large-format printer. “I like keeping this little Hollywood dream bubble from popping,” he tells me. We leave the painter to his work: Alex wants to show me more.

The prop rooms, the workshops: there are halls of doors, halls of windows, halls of furniture, halls of knickknacks—in every conceivable style, from every conceivable period. Gothic sits next to midcentury modern sits next to Greek antiquity sits next to overstuffed suburban beige. It’s a bit like the last scene from Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981): the interminable military hangar full of TOP SECRET crates in which the Ark of the Covenant is locked away. By virtue of being props, having played their inanimate role in the production of pop culture, they escape their mundanity. “It’s stardust,” according to Alex. Maybe this is why in his first solo gallery show, Property (2011) at Peres Projects in Berlin, he featured props framed by abstract painted backdrops (Flats) cut in the shapes of Spanish Revival windows and rendered in hot color gradients inspired, like Ed Ruscha’s paintings, by Angeleno sunsets. The prop becomes readymade, the sunset extrudes on a stucco-textured ground. Decontextualized, the prop is ordinary. It can’t hide behind lighting and visual effects (VFX). Yet it retains a bit of movie magic—a bit of stardust.

In a room of Roman busts, Alex tells me these are replicas but that the studios had real artifacts once upon a time. Consortiums of archaeologists, historians, and museum boards pressured the studios into relinquishing the antiquities to the proper authorities. I’m both shocked and amused. Using real Roman statuary as a prop in a twentieth-century epic called to mind the Pre-Raphaelites’ favorite color: mummy brown. They completed their paintings using the ground-up remains of ancient Egyptian mummies as pigment, an important reminder that historical preservation is a relatively new phenomenon.

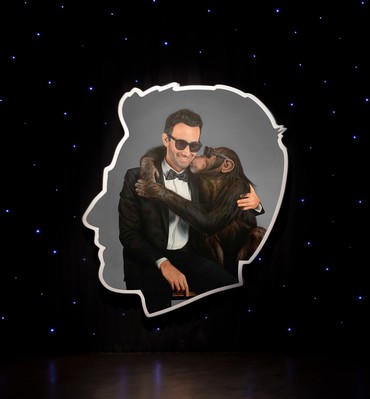

Israel’s self-portrait with Eli, the last trained Hollywood chimp, is an indicator that many of our present-day media production practices may be seen as similarly outlandish in the future. Not all obsolescence has a moral valence, though; scenic painting has simply been pushed out by the convergence of efficiency and technology. (See the flattening effect that streaming-platform creative guidelines and cheap VFX have had on movies of late.) Does film grain have more stardust than digital video? Does a trained chimp have more stardust than a CGI stand-in? Alex Israel’s work endeavors to find out.

Alex understands object aura. And like any good Angeleno, he knows it comes in both authentic and kitsch flavors. His negative-relief Oscar sculpture, Casting (2015), was made with an abandoned prop that he located in a Cinecittà warehouse. (The Academy jealously guards its three-dimensional IP.) His replicas of the crystal egg from Risky Business (1983) and the black onyx Maltese Falcon from the eponymous 1941 film—Risky Business (2014–15) and Maltese Falcon (2013)—toe the line between memorabilia and art object. Authentically Alex Israel rather than authentically collector’s items. Conversely, the thirty-foot American Idol sign adorning his studio is the real thing. (He scored the monumental memorabilia during the interim between the show’s cancellation by Fox and its revival by ABC.) The issues at stake in the meaning of these objects replay the Duchampian issues of readymade versus artwork and original versus replica. When Alex displays a prop created for one of his own movies, like a surfboard from SPF-18 (2017), does it have more or less stardust? It’s a nose-to-tail perspective on media production that makes sense only from the belly of the beast, the Dream Factory itself.

Alex Israel is a conceptual artist who works with the materiality of media. It’s an insight that comes from living behind the world’s most famous stage—Los Angeles. For the consumer, media seems like shadow play: light and celluloid, zeros and ones. But the producer knows that media’s immateriality is quite literally smoke and mirrors. Media is a document of people, places, things, and ideas. Movie magic means forgetting this fact, much like a postindustrial United States forgets there are factories in China. But nostalgia means remembering.

At its core, nostalgia is a media phenomenon. When works from classical antiquity by Plato, Socrates, and others found their way back to western Europe after the Middle Ages via manuscripts of Arabic translations, we got the Renaissance. When TikTok teens began digging through their older siblings’ Facebook albums from their scene days, we got the e-boy. There’s excitement in discovering the world before you—even if you can access it only through the half-truths and misunderstandings of the past’s media artifacts.

Throughout the latter half of the twentieth century and into the twenty-first, we’ve seen the nostalgia cycle hit like clockwork every fifteen to twenty years, as teens look just beyond the horizon of their own consciousness and obsess over the era just before they came to be. In the 1970s, teens looked to the 1950s with Rebel without a Cause (1955) leather jackets, the Happy Days (1974–84) period sitcom, and the Grease (1978) period musical. In the 1990s, teens looked to the 1970s with The Virgin Suicides (1999) and louche mod style gleaned from the finished basement’s wood-paneled rec room. In our most recent decade, the 2010s, teens got the normcore reformulation of Friends (1994–2004) ending in the crescendo of HBO Max’s Friends: The Reunion (2021), and the gonzo streaming spectacle of Pen15 (2019–), wherein millennial comedians Maya Erskine and Anna Konkle reperformed their own Y2K tween angst for Hulu. This is of course a simplification. The pattern is noisy but certainly present.

Unlike the nostalgia of the hipster dad with the sleeve tattoo bemoaning yet another Williamsburg DIY space that has become condos or the boomer trying to Make America Great Again, teen nostalgia is evidence of neither arrested development nor reactionary politics. Though this is the sentiment’s least pernicious form, it is teen nostalgia that inspires the most bile. Look only to the ongoing generational war on TikTok. The teens call thirty-something millennials geriatric. Millennials respond hilariously in kind. Youth makes us anxious. If they are the future, why are they so interested in the past? If the teens are nostalgic, how can we be sure they’ll build the world of tomorrow? We want them to fix all the world’s problems—though we’d rather not say who created them . . .

Further complicating this irony, our concept of The Teen™ itself seems increasingly nostalgic. If we look closely at Alex Israel’s work, we can see the contours of The Teen™ as a media archetype. His Freeway sunglasses brand channels the SoCal teen bad boys of the past: Ellis and the banal cocksucking zombies of Less than Zero (1985), as well as drag-racing James Dean memorialized forever with his Griffith Observatory bust perched over the Southland sprawl. The obsession with eyewear reaches abstract, sculptural proportions in Israel’s series of lens sculptures. Gigantic and curved in jewel tones, they lean discarded against the gallery wall.

Israel’s YouTube show As It Lays (2012–), the title an homage to the novel Play It as It Lays (1970) by fellow Californian Joan Didion, whose minimalist prose so influenced Ellis, features the American Psycho (1991) author in its inaugural episode. Billed as a series of video portraits of Tinseltown’s finest—a quick survey of interview subjects reveals a who’s who of teen icons and the industry titans who created them: Kris Jenner, Whitney Port, Stephen Dorff, Perez Hilton, Jamie Lee Curtis, Evan Spiegel, Alicia Silverstone, Belinda Carlisle, Darren Star, Corey Feldman, LL Cool J, Paris Hilton, the list goes on. The show bills itself as being about Los Angeles. But Los Angeles has always been about youth. It is the spiritual homeland of The Teen™.

Israel, in the role of host, performs the appeal of eternal adolescence, never removing his Freeway shades. In its first season, from 2012, the opening sequence has the cadence of The Hills (2006–10): upbeat music, helicopter shots of Malibu, time-lapse freeways, a fit man diving David Hockney–style into a serene blue pool, an obligatory clip of a neon sunset over downtown LA, an iconic shot of the Hollywood sign itself. The set is designed around Alex’s favored light-blue-to-pink-to-orange gradient. Again we see polychrome paintings on stucco—like those that provided the backdrops for his then-recent prop show, Property (2011)—only this time the props are the personalities we all know in that mediated way we call celebrity. Questions are simple, staccato. Israel asks, “As a child, how did you answer the question, ‘What do you want to be when you grow up?’” Molly Ringwald answers, “It’s really embarrassing, but I think I said that I wanted to be a famous movie star.” In Los Angeles, the fiction of the self always arcs toward fame . . . or something approximating it. Celebrities, like props, can have an uncanny quality. It’s the stardust.

In its second season, from 2019, the As It Lays set mirrors the luxe aesthetic of The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills (2010–): white roses, white latticework formed into arches in the lush shade of a Spanish-style tiled courtyard, decontextualized pseudo-European railings and moldings. The opening sequence takes advantage of advances in drone technology and its attendant impact on B-roll footage: we sail over the intersection of the 10 and 405 freeways, Echo Park Lake, Mulholland Drive. Again its subjects are LA locals. This season Alex still keeps his sunglasses on inside but glams up his outfit with a white tux courtesy of Giorgio Armani, Beverly Hills—a nod to reality TV decadence. The questions remain prepared but lean into the comedic. Israel asks Charlie Sheen, “When Meatloaf proclaimed, ‘I would do anything for love, but I won’t do that,’ what do you think he wouldn’t do?” To which Sheen replies, “Maybe butt sex, I don’t know.” With social media thinning the membrane between everyday life and entertainment, stars are ready to be candid. What more can be revealed?

Our recent cultural shift from a mass monoculture produced and directed by Hollywood and its entertainment industry to a decentralized and fragmented internet culture powered by (Northern) California’s Silicon Valley—but produced everywhere—begins to complicate California’s hold on The Teen™. In his teen surf drama SPF-18 (2017), Alex presciently cast softboy-teen-heartthrob-verging-on-chad kitsch icon Noah Centineo as its romantic lead. (The film was the first art piece to stream on Netflix, the platform that subsequently popularized Centineo in teen romcom content with its Originals series.) Israel bridged the old California of surf films and network television by collaborating with the writer Michael Berk, creator of the iconic 1990s TV show Baywatch (1989–99). Baywatch and Netflix represent California past (pop culture) and California future (internet culture). Alex’s Janus-faced perspective is revealed in cameos by teen icons past—Pamela Anderson, Keanu Reeves, Molly Ringwald—backing up teen icon future Noah Centineo.

Does it then make sense that Alex Israel graduated high school in the year 2000? He tells me, “I still feel like I’m sixteen years old.” When Alex was properly a teen, the genre of the surf film was a retro West Coast throwback: the counterpoint to Rebel without a Cause and its archetype of the troubled bad boy, surly in blue jeans, existential in outlook. Films like Beach Party (1963) presented The Teen™ as fun-loving and free.

This ethos matched the Los Angeles of Israel’s adolescence. Very much a creature of the cultural climate, postwar LA was prosperous, ahistorical, automobile-oriented, suburban. From the vantage point of 2000, the last year of “The End of History,” the last year of post–Cold War exuberance, these terms made sense. From the vantage of 2021 (closer to 2050 than 1950), those adjectives feel increasingly outdated: inequality and gentrification are watchwords, manifest destiny has been debunked, there’s a subway to the sea underway, downtown has undergone Manhattanization. Similarly, the formula that created the teenager as a sociological object—a broadly wealthy society in which young Americans were accorded a half dose of maturity with a full dose of independence—no longer seems to exist.

Teenagers today are poorer than the average American. It’s unclear whether this will sort itself out as they get older. They socialize less outside the home. They learn to drive later, have sex less frequently. They don’t smoke, barely drink, and hardly do drugs. They’re more worried about social media than older Americans. They stress about cyberbullying, body image, cancel culture, privacy. Their parents monitor them more closely, push them to spend more time studying, and encourage a hypercompetitive focus on school. It makes me wonder: Were millennials the last generation of teens? Was The Teen™ a twentieth-century phenomenon? Once rambunctious, rebellious, unsupervised, empowered—now obsolete?

If the teen is the old social technology—the old cultural script—for becoming a person, it has surely been replaced by another California export: the personal brand. Alex Israel’s work sits where the trend lines cross. His Self-Portraits series exemplifies this best. Influencers may package theirs in an Instagram grid, and Israel may package his in a survey exhibition, but both understand that the key to engagement is difference and repetition. The selfie is the signature for the postliterate age. It’s an alibi for content. Israel’s various iterations drill down into his interest in the material culture of the Dream Factory: hot girl Instagram stories at Coachella, PCH, the Santa Monica Pier, the Wheel of Fortune, the Palisades High School hallway from Carrie (1976), Disneyland, Venice Beach’s skaters, Malibu’s surfers, an early 1990s teen’s bedroom complete with graphic bedspread and requisite Sony Walkman. These scenes are interspersed with his ubiquitous gradients: the color of sky, the color of dimming theater lights, and the color of Instagram filters.

It’s a bit offhand to call an artist a personal brand in 2021. Who isn’t? But Israel claimed that bit of cultural terrain first. Like the influencers of Calabasas, he leaves merch and collabs in his wake. For the preferred teen hangout and health-conscious caffeinated alternative Cha Cha Matcha, Israel created a custom frozen vegan swirl with a matching cup based on his Sky Backdrop paintings. Eponymously titled, the ice cream is flavored with strawberry and blue algae. It renders in a blend of pink and blue. As he prefers, this collab mirrors his more traditional work: a finely carved marble simulacrum of frozen yogurt, The Bigg Chill (2012–13). As with a frame in a film, a celebrity moving between roles, a set being refitted for a new series, nothing is lost. Creativity is found in the repetition. His gradients also repeat, reemerging in other projects, like a collaboration from 2019 with the luggage brand Rimowa. California haze serves as a departure point for paintings, ice cream, logos, sculptures, and an aluminum suitcase colorway.

For the preferred Gen Z social media platform, Snapchat, Israel created a series of augmented reality (AR) lenses—software in metaphoric parallel with his Lens sculptures. Debuting at the Cannes Lions International Festival of Creativity, the most iconic image was Alex Israel × Snap, Self-Portrait (Pelican with Fish) (2019)—software in literal parallel with his realistic kinetic sculpture Pelican (2018). Israel confided that he considers the Santa Monica Pier residents his spirit animals.

For the preferred hypebeast luxury brand Louis Vuitton, Israel has crafted fragrances that smell like Los Angeles, scarves, and of course an iconic bag. Textiles feature cacti, convertibles, desert roads, as well as the wave motif that carries across the leather accessory. Again the collaborations mirror Alex Israel’s oeuvre—his memeplex. Waves render on wall works as paintings permuting through colors and gradients. Waves render on cowhide as an It bag. Waves find their inspiration in the surf shots featured in his YouTube series and his Netflix film.

From thirty thousand feet, these practices both anticipate and reveal what happens when there is no longer an art world so much as art spaces, when there are no longer individuals so much as personal brands. The art world is eroding. The postwar order emancipated the individual from tradition, freed them to experiment toward the end of self-expression, self-discovery. The media script of The Teen™ was the road map for the individual to find themselves. The new script of the personal brand is the response to our accelerated content ecosystem. The artist isn’t a symbol of freedom but an agent of authority. They understand the shimmer of aesthetics. They’ve mastered their meaning. Their conceptual gestures are an exercise in control.

Alex Israel: Freeway, Fosun Foundation, Shanghai, November 11, 2021–March 6, 2022; Fosun Foundation, Chengdu, China, April 21–May 15, 2022

Artwork © Alex Israel; text © 2022 Sean Monahan