Sergio Risaliti is an art historian, writer, and curator of exhibitions and interdisciplinary events. He founded the Palazzo delle Papesse, Siena, and served as its director until 2002. Since 2014 he has acted as artistic director of projects at the Forte di Belvedere, the Stefano Bardini Museum, the Palazzo Vecchio, and the Piazza della Signoria, Florence. Photo: Giovanni De Angelis

What you have inherited from your fathers

Earn over again for yourselves or it will not be yours.

—Goethe, Faust, 1808

One must still have chaos in oneself to be able to give birth to a dancing star.

—Friedrich Nietszche, Thus Spake Zarathustra, 1883–85

In an era when the avant-garde seems to have lost the propulsive power it had in the previous century, as if the limits of progress had been reached, while tradition offers the possibility of reopening paths previously abandoned, the paintings of Jenny Saville both recognize known types of beauty and at the same time are able to subvert them. Her nudes, her portraits, her studies of motherhood, her “sorrows,” are so contemporary yet so classic that we feel pulled in opposite directions and cannot remain indifferent; they overwhelm us. We realize we have to confront her painting with all our senses, profoundly involved and tested in the face of what we cannot help but experience as a mysterious visual shock.

Since Saville’s early career, her paintings have seemed both sumptuous and aggressive, both poignant and serene, both abject and moral. Immune from vulgarity and obscenity, they are tragic at heart but overflowing with grace and tenderness. Having calmly moved beyond the conflict between modernism and the figurative tradition, her art is the perfect synthesis of the ambition for universality and a realistic passion for what is contingent and present. Hers is its own program, particularly when it looks for comparisons with masters from the past and with themes or subjects from art history. Never satisfied with her achievements and always thirsty for experiment, Saville celebrates life beyond suffering and nihilism, life in the knowledge of death, that inevitable destiny that makes us human, anguished, heroic in despair and generous in compassion. We see in her paintings the incarnation of the past, with all its battles won and lost, its traumas and fragilities. We recognize our humanity, civilized and at the same time still primitive, emancipated and at the same time still subservient. It is pointless to ask whether the epiphanies in her work lie in her always powerful and recognizable images or if they occur through a paint application that is often dense, oily, now angry, now sweet, as careful in the definition of detail as it is aggressive in sketching out contours over and over again, as if searching for a fixity and completion belied by the mobility and blurring of the subject.

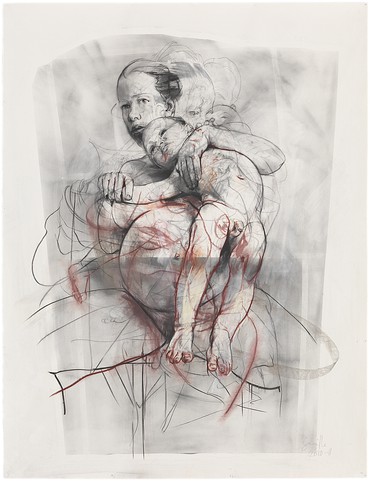

In recent years Saville has grappled with a primordial subject: motherhood. She has experienced the transformation elicited by the “movement of one body toward two,” as she has described childbirth, in her own body. That growth within her left its mark on her work: “I continued to think about the formation of flesh and limbs within my body, about regeneration. . . . My various drawings one upon another are a way to communicate these feelings. You are literally reproducing when you are pregnant, like the way in which lines reproduce.” When I think about works such as Generation (2012–14), Study for Isis and Horus (2011), and The Mothers (2011), I cannot help but remember the countless appearances of the mother-and-child theme in art, and not only in the figurative art in the museums but in other symbolic systems of human communication: photographs, movies, poetry, literature, theater. Saville positions her work amidst all such depictions, whether ancient or modern, archaic or Renaissance. Her art is absolutely new, presenting the subject with a completely original truth and passion. She puts us inside everything we can imagine, whether as men or as mothers: heart and mind, blood and flesh, pain and ecstasy, instinct and sensation, archetype and idealism, trauma and pleasure. Finding its place among both the votive statues of the primordial era, which had a magical, apotropaic relationship with birth, growth, and death, and the idealized forms of Renaissance madonnas, pregnant with religious feeling, her work offers a female perspective that previously has rarely been taken into account.

In a series of drawings from 2010 and 2011, Saville returned to Leonardo’s cartoon The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne and the Infant Saint John the Baptist (c. 1499–1500), in the National Gallery, London, and Michelangelo’s Madonna and Child (c. 1525), a perfectly executed autonomous work, in white lead, black and red pencil, and ink, in the Casa Buonarroti museum in Florence. The Michelangelo drawing is almost a challenge in graphic form to earlier sculptures of the artist’s such as the Madonna of the Stairs (c. 1490) and the Madonna of Bruges (c. 1501–04), youthful works, or the Medici Madonna, begun around 1526 and perhaps completed in 1534, when Michelangelo was forced to leave his hometown of Florence, never to return. In the Medici Madonna, in the Basilica di San Lorenzo, Florence, the Christ Child, in Giorgio Vasari’s words, “twists” like a sturdy young athlete, “straddling his thighs” on the body of the Virgin. He makes this contortion to hide from our gaze, perhaps clutching his mother out of fear, as if we were his executioners, while she, preoccupied with her own, prescient thoughts, looks in a completely different direction, away from both us and her son.

This type of athleticism was one of the ways in which Michelangelo handled contrapposto, using it, as he also did in his sublime poems, as a way to interpret and communicate, whether through three-dimensional or graphic forms, the complexity of the movements of the soul, setting the animal-like, disturbing dimension of physicality and sexuality in dialogue with our divine nature, as called for in Neoplatonic thought. In the end, this was also the goal of Michelangelo’s well-known non-finito or unfinished work: to create a dynamic contrast between matter and spirit, earth and heaven. These interests have clearly been central to Saville, and she has returned to them recently in confronting the Renaissance art of Florence for this exhibition in five museums in the city, the Museo Novecento, the Palazzo Vecchio, the Casa Buonarroti, the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, and the Museo degli Innocenti. No living artist has ever been given such an opportunity.

During a visit to the Casa Buonarroti shortly before the pandemic halted all movement between countries and cities, Saville was for the first time able to view Michelangelo’s Madonna and Child in person, a strongly emotional experience for her. I was present that day, and have rarely witnessed such deep and respectful concentration. After a meeting with members of the museum’s administration, the decision was made to exhibit a group of Saville’s works, including Study for Pentimenti III (sinopia) and Study for Pentimenti IV (after Michelangelo’s Virgin and Child) (both 2011), in a single space with the world-famous Madonna and Child. The collection of this small museum, of course, is laden with history and with masterpieces by Michelangelo, including the Madonna della Scala (Madonna of the stairs, c. 1490), the Battaglia dei centauri (Battle of the centaurs, 1490–92), the wooden Modello per la facciata di San Lorenzo (Model for the facade of San Lorenzo, c. 1518), and hundreds of drawings, letters, and poetry manuscripts.

There is also an Etruscan funerary urn, which Saville considered showing near one of her more complex and I would say atemporal paintings, Compass (2013). This work depicts a naked couple (although four figures can be recognized) stretched out, although not completely, as if for conversation before or after sex. Their warm and luminous beauty exudes both concupiscence and something higher, otherworldly, and belonging to no one gender. Saville is constantly drawn to formal and conceptual ambiguity, to hybrid and superimposed forms and to blurred and tangled contours, as, for example, in a drawing by Leonardo that she especially loves, a study for the Saint Anne cartoon in the British Museum (1505–08). In this work that is almost a scribble, the figures are so confused and overlaid that it is impossible to distinguish them from one another. Saville preserves the same ambiguity when she deals with the definition of gender or the boundary of human emotions and feelings, excavating the recesses of the psyche.

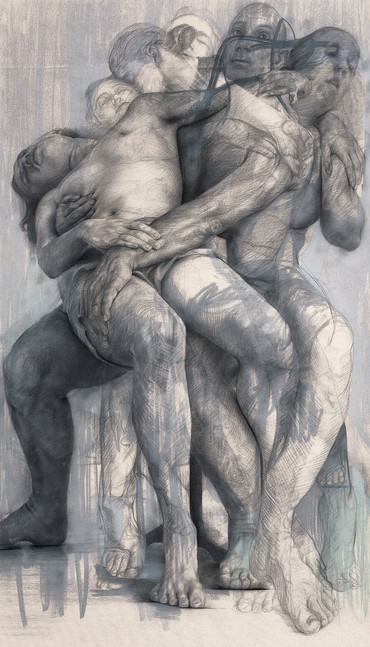

Florence, that cradle of the Renaissance, offered Saville another surprise: the possibility of exhibiting a work in the room holding Michelangelo’s Bandini Pietà (c. 1547–55) in the newly renovated Museo dell’Opera del Duomo. That museum also houses other masterpieces of Renaissance sculpture, including the doors of the San Giovanni baptistry and Donatello’s several Prophets and Penitent Magdalene (1453–55). Saville was able to study the Bandini Pietà twice on site. During one visit, she spoke with restorers cleaning the marble and was able to see new details, close up, that inspired and moved her. This resulted in Study for Pietà, a large drawing, over six feet high, in charcoal on raw canvas, almost an attempt to maintain a formal relationship with the roughness of the stone sculpted by her great colleague over four centuries ago.

The Bandini Pietà, also called The Deposition, is one of Michelangelo’s last works: when he began working on this enormous block of white Seravezza marble, more than six feet high, in his studio in Rome, he was about seventy-five. Needing to obtain a group of four figures, and wanting to depict different moments in the passion of Christ, from the deposition from the cross to the entombment, he had to compress the figures’ bodies, resorting to expedients familiar in painting but unusual in sculpture—effects of distortion and foreshortening of the limbs and of the multiplication of viewpoints, valuable in dynamizing the telling of the story. Saville understood this strategy perfectly and her drawing too compresses her group of five figures. She has studied their positions as if for a passage of choreography, and certain elements—arms and hands—are left to the imagination, while the feet do not seem to correspond to the bodies.

Like these works by Michelangelo, Leonardo’s Virgin and Child with Saint Anne . . . holds particular interest for Saville. This figural group—the Virgin, the Child, Saint Anne, and Saint John the Baptist, the Messiah’s cousin of the same age—is complex in its pyramidal structure. Like Michelangelo, Leonardo seems to constitute a sort of experimental laboratory for Saville, who, between 2009 and 2010, created a series of drawings, Study for Pentimenti and Reproduction for Drawing, whose multiple jumbled, nervously and rapidly sketched silhouettes convey the tension of her research. The body of a newborn appears many times, almost in conflict with its mother, as if it were becoming physically and psychologically aware of their bond and of the urgent need for detachment. The images transmit the animal energy that flows between mother and baby. One of these drawings, in pastel and oily charcoal, with oleaginous stains and fine, subtle traces, is titled Componimento inculto (Uncultivated or wild composition), a phrase of Leonardo’s that Ernst Gombrich used to explain certain tangled drawings that the artist seems to have created in one rush, in a spur-of-the-moment observation or experiment.

Saville’s interest in earlier art shouldn’t surprise us; she has always looked at the old masters, seeking ways to embody the spiritual in the material, to leave behind the superficial flatness of the photograph, which she, like Francis Bacon and Edgar Degas before him, uses as a point of departure from which to reach a far distant place. In the halls of museums and other sacred places of art, she knows just what to look at and how to look at it. Take, for example, her tendency toward the monumental: was it not perhaps Tintoretto or Rubens, Géricault or Delacroix, that guided her here? Her response to the challenge was the eight-by-sixteen-foot canvas Fulcrum, with which she staked her claim, while still very young, in an exhibition at Gagosian, New York, in 1999. The first thing we see in that painting is an enormous lump of flesh, in which, with difficulty, we eventually make out three figures. Heads and faces, feet and limbs, gradually come into focus, seemingly weighed down by the fatter body parts. Although the canvas is grandly large, the surface seems small, so filled is it with flesh, which seems forced into a space insufficient to contain it. Fulcrum will be exhibited at the Palazzo Vecchio, in the Salone dei Cinquecento, decorated by Vasari after the 1550s. All the paintings there are battle scenes celebrating the wartime power of Florence and the supposedly divine mission of Duke Cosimo I de Medici. Masses of armed figures engaged in combat—there are obviously no women. The Salone is further embellished with sculpture, including Vincenzo de Rossi’s several Fatiche di Ercole (Labors of Hercules, 1562–84) and Michelangelo’s Genio della Vittoria (Genius of victory, 1532–34), an extraordinary example of anatomical contrapposto, left unfinished. From a formal standpoint, Saville’s work seems to ask for direct comparison with the language of sculpture, given the monumental size of her images and the strong plasticity of their figures.

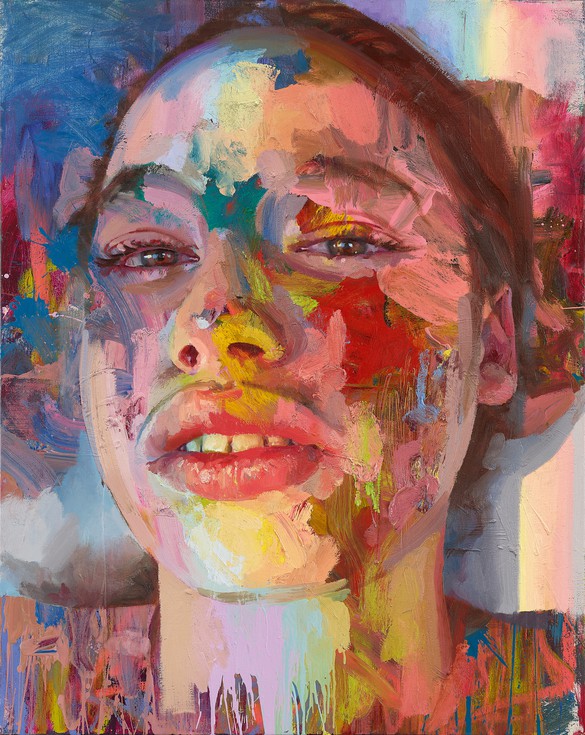

In a retrospective of at least one hundred of Saville’s works installed in these various museums, portraits—always large scale, always frontal—reign supreme. There are faces of young men and women of archaic beauty, an Olympus of European and other divinities, with profound, intense gazes that look at us from the height of their incorruptible morality. As undistracted as the portraits of Fayum, in ancient Egypt, they remain totally concentrated within the bounds of their unattainable intimacy, as in Messenger (2020–21), or Arcadia, Prisme, Circe, Ligea, and Iris from 2020, where the gaze is directed elsewhere, upward and far away, toward a distance equal to the infinity that each of them contemplates and perceives within themselves.

The titles refer to the great myths of the Mediterranean, as well as to metamorphoses, the nature of light and color, and feelings of panic. They remind us that gods and men once clashed on cliffs or in battle, in forests or on beaches. The faces all have aura, that unbridgeable distance that Walter Benjamin invokes to explain the spiritual resonance of art before the age of mechanical reproduction. We know that life can work on faces, scarring them, crushing them, stripping away their flesh, ruining them, to the point of rendering the sitter unrecognizable. Yet if it is true that each of us bears the mark of a higher provenance, a cosmic energy that neutralizes evil and nothingness, the beauty of every face is then the reflection of an inner beauty; and sometimes life is generous, and reveals to us what true beauty is in people’s faces, illuminating their immensity. Those faces radiate a pure solar energy, convincing us of the idea that we are infinite.

Translated from Italian by Marguerite Shore

Artwork by Jenny Saville © Jenny Saville. All rights reserved, DACS 2021