Douglas Dreishpoon, chief curator emeritus at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York, is currently director of the catalogue raisonné project at the Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, New York, and consulting editor at The Brooklyn Rail. His book What Is Modern Sculpture?, part of the Documents of Twentieth-Century Art series, is forthcoming from the University of California Press.

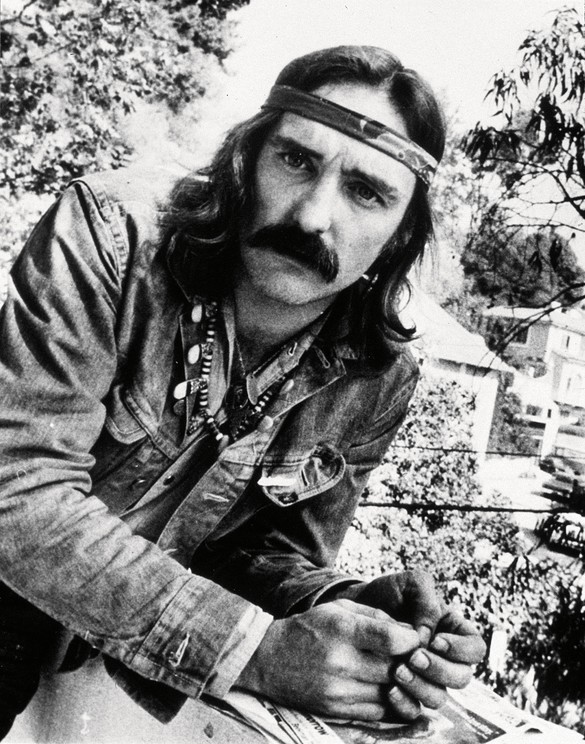

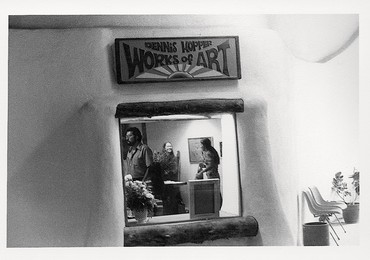

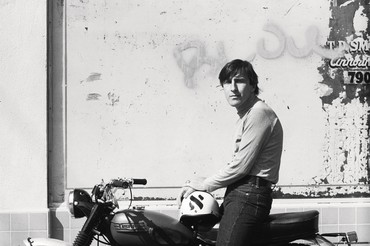

No one looked more surprised than Dennis Hopper on the morning of May 6, 2009, as he was appointed honorary mayor of Taos and presented with a key to the city. Forty-one years earlier, when the long-haired first-time director stormed the town to film Easy Rider and cruised through a deserted Taos Pueblo with Peter Fonda on a pair of choppers, such a tribute would have been unthinkable—akin to handing over Gotham City to the Joker. To local Taoseños, Hopper and his crew appeared like an alien invasion, a perception amplified by his countercultural encampment a few years later at the Mabel Dodge Luhan House during postproduction on The Last Movie (1970–71). But on that calm spring day in 2009, a jubilant assembly of artists, reporters, politicians, and supporters packed the Harwood Museum of Art to celebrate the fortieth anniversary of the release of Easy Rider and to preview the exhibition that Hopper had organized around the work of his longtime friends and fellow Taos settlers Larry Bell, Ron Cooper, Ronald Davis, Ken Price, and Dean Stockwell.1 The scene was surely surreal. If you live long enough, most of your detractors disappear and most of your notorious deeds are forgotten. Surrounded by well-wishers, Hopper seemed to relish the moment as an auspicious gift.

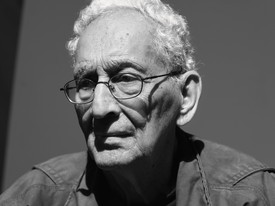

“I’ve never had a lot of direction in my life,” the spry seventy-three-year-old admitted with a laugh during our interview at the Harwood three days before the celebration. “I sort of follow the bee, you know, to the honey. It’s not like my life is some miraculous thing, I just leave myself open. The trail may not be going that way.”2 The many trails that Hopper blazed during the course of his remarkable life didn’t always lead to a pot of honey. Some were as focused as the relentless interstate highway that crosses his native state of Kansas; others were as unpredictable as the path of a skittish horse. Leaving himself open became a survivalist’s credo: a way to rebound and reinvent himself, time and time again, by simply rewriting the rules of his own game.

If life’s dice had landed differently, the restless youth from Dodge City might have become an artist instead of an actor. Introduced to art by “a Rocky Mountain watercolorist,” the rambunctious farm boy naturally gravitated to it, learning to sketch from life in art classes at the Kansas City Art Institute. But he also got into acting, watching westerns in the town’s silver-screen movie theaters and, during his high school years, taking drama classes in La Mesa, outside San Diego. And early on, he realized that acting, besides being a golden egg, could be the vehicle through which everything else—filmmaking, photography, art collecting—would become possible.

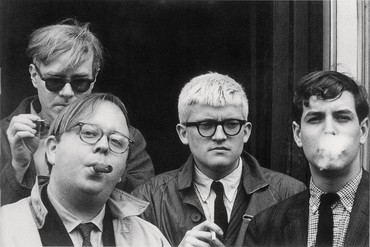

Hollywood’s dream machine is amoebalike in its ability to absorb the creative energies of anyone willing to enter its cinematic cloud. The culture it spawned during the late ’50s and ’60s exploded as a constellation of crossovers and cross-fertilizations, actors commingling with artists, performers, poets, writers, and experimental filmmakers. James Dean’s method-driven performances in Rebel without a Cause (1955) and Giant (1956) deeply impressed the nineteen-year-old Hollywood hopeful who cut his teeth on the same sets. Hopper idolized Dean, who taught him how “to trick the imaginary line” between one’s actions on and off camera and encouraged him to pursue photography. Dean also advised him to get to know artists in his spare time, which he did through Stockwell, another actor and close friend, who, along with Dean, introduced him to the Stone Brothers print shop in West Los Angeles. Everyone he met there—the print shop’s founders, Walter Hopps (who, soon after, with Ed Kienholz, started the Ferus Gallery), Wallace Berman, and Robert Alexander; as well as Kienholz and George Herms—sharpened his aesthetic consciousness and in the years that followed became subjects of his photographs.

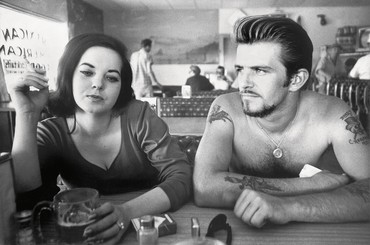

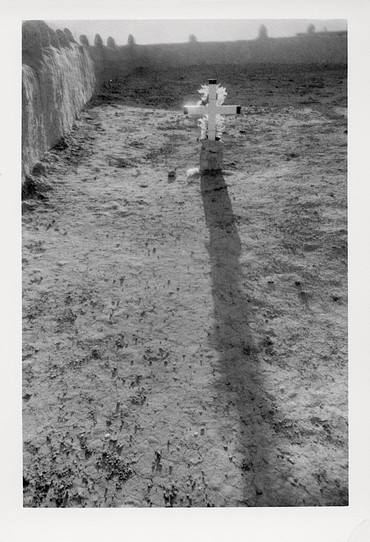

More than painting and sculpture, it was a portable Nikon—a present to Hopper from his first wife, Brooke Hayward—that best suited his quicksilver sensibility. Loaded with black-and-white Tri-X film, it allowed him to seize decisive cultural moments with an uncanny sense of timing. “Where did Dennis Hopper come from?” mused Herms. “How many times was he on the scene . . . on the spot . . . in the world of art, Hollywood, the civil rights movement? This gift of being almost prescient is rare.”3 In the half-dozen years leading up to the production of Easy Rider, Hopper clicked off an astonishing stream of images. “In a curious way,” Hopps recalled in 1986, “what seems special about Hopper’s photographs now is that they seem to resemble still shots from movies. Not so much frames from films but still photographs made on the sets and locations of imagined films in progress . . . wonderful ones.”4

The sets of these imagined films are populated in the main by an expanding circle of art-world friends and musicians, sometimes photographed in public settings but more often in studios, galleries, and private homes. Other images, of the civil rights march from Selma to Montgomery, document a tumultuous arena far from Tinseltown. The quest for equality against a rising tide of bigotry inevitably bled into the script for Easy Rider, Hopper’s directorial debut and, regrettably, the end of his photographic roll.

Hopper’s saturnian temperament may explain why he trusted kindred artists, whose dedicated patron he became. The art of others sustained him through highs and lows, multiple divorces, and rehabilitations. He plainly liked having art around him and acquired it with a vengeance from 1961, when he was living with Hayward in New York, until his death. If art offered some kind of solace, so did the small tribe of artists who followed him to Taos in the ’70s and in whose company he rose. That’s what I observed on the afternoon of May 4, 2009, when Dennis joined Bell, Cooper, and Stockwell at the Harwood to reminisce. Their brief reunion, coupled with my one-on-one conversation with Hopper the day before (excerpts below), now seems like a reprieve as the actor neared the end of his life’s trail.

Dennis Hopper died on May 29, 2010, and is buried in a small cemetery in Ranchos de Taos.5

Douglas DreishpoonWe’re at the Harwood Museum in Taos. This month [May 2009] marks the fortieth anniversary of Easy Rider. With that cinematic milestone came the invitation to curate an exhibition around the work of your Los Angeles friends Larry Bell, Ron Cooper, Ron Davis, Ken Price, and Dean Stockwell. How did you discover Taos?

Dennis HopperPaul Lewis, production manager on Easy Rider, and I were driving cross-country scouting locations. We were coming down from Farmington, New Mexico. We’d gone through Dulce, across the Jicarilla Apache Reservation, and down through Coyote and Abiquiú. When we got to Española, Paul said, “Well, if we turn right, we’ll go to Taos, an art colony. If we turn left, we’ll go to Santa Fe.” I said, “Well, I don’t want to go to any fuckin’ art colony. We’re making Easy Rider here, man!” But we went the wrong way and ended up in Taos. That’s how I first got here, and, as a location, it worked. I shot at the town jailhouse, the Indian pueblo [Taos Pueblo], and Manby Hot Springs.

DDWas it difficult getting access to certain sites?

DHThe pueblo was problematic because they didn’t want a movie being shot there, particularly with motorcycles. It was also a time of ceremonial kivas. So we offered to shoot without anyone around. The elders agreed to that.

DDI’m interested in the film’s storyboard, how the script got written by you, Peter Fonda, and Terry Southern. Who came up with the hippie-commune scene?

DHWell, it wasn’t cowritten. Peter and I talked through a lot of ideas. He didn’t want any farmers, he wasn’t sure about the hippies, but we got through the process and had an outline. The year before, I spent almost every weekend hanging out in San Francisco, around Haight-Ashbury and Berkeley. I knew what was happening and what the film needed. Peter and Terry went off to New York City to write the screenplay while I scouted locations with Paul. When we got to New Orleans, I called and asked, “How’s it going?” We already had a complete outline; all they had to do was fill it in. Peter said they hadn’t written anything. I freaked out, got on a plane, went to New York, kicked everyone out, and in ten days wrote the script.6 There was a lot of improvisation on set but I knew where the film was going.

DDTalk to me about acts of improvisation.

DHPractically the whole fuckin’ thing was improvised. Except for certain scenes that were written, but even some of those were improvised. Like when Jack [Nicholson] gets turned on for the first time and sees flying saucer people in space.

DDThat scene reveals extreme character differences. Fonda’s character, Wyatt, tends to be taciturn and introverted. Billy is far more loquacious, animated.

DHI do what Steve McQueen said an actor should never do: I explain everything.

DDHow did you sign on Nicholson?7

DHBert Schneider [one of the film’s producers] wanted Nicholson. I knew Jack, because we’d both been in AIP [American International Pictures]. He’d written the script for The Trip (1967), which Peter and I had been in, along with Bruce Dern and Susan Strasberg (Lee Strasberg’s daughter). He also appeared in Hell’s Angels on Wheels (1967) and co-wrote, with Bob Rafelson, Head (1968), starring the Monkees, with an appearance by yours truly. Easy Rider was essentially a countercultural motorcycle movie. Jack was originally from New Jersey. He was a damn good actor; I just couldn’t see him as the alcoholic country-bumpkin lawyer. But I was wrong, he was brilliant. He also convinced Bob Rafelson and his associate Schneider that they should let me direct and act in the film.

DDWhere was postproduction done?

DHAt Columbia Pictures, where I was banned at the age of eighteen for telling [cofounder, president, and production director] Harry Cohn to go fuck himself after he criticized my doing Shakespeare at the Old Globe Theater in San Diego. He kicked me (and my agent) out of the studio. Fifteen years later I returned to edit Easy Rider. Columbia distributed the film.

DDYou eventually returned to Taos and purchased the Mabel Dodge Luhan House.

DHI fell in love with Taos and thought, If I ever get any money, I’m going to come back here to live. After Easy Rider came out and was a runaway success, I shot The Last Movie in Peru and sent all the footage to my younger brother, David. We needed a place to edit. When I came back to Taos, the Mabel Dodge House was available, including the original furniture, for $140,000.

DDDid you know much about Dodge’s life story?

DHNot a lot. I knew that [D. H.] Lawrence had been there, that Dodge had written some books, and that Tony Luhan was the son of the chief of the pueblo. I’ve never had a lot of direction in my life—I sort of follow the bee, you know, to the honey. It’s not like my life is some miraculous thing, I just leave myself open. The trail may not be going that way. I edited The Last Movie at the Mabel Dodge House and ended up staying in Taos on and off for about nine years.

DDSome folks say your time in Taos was mostly spent defending yourself against ghosts while trying to finish the film. But there were sideline interests, too. You got involved with progressive politics—the Black Mesa Defense Fund.

DHYeah, the Peabody Coal Company was illegally destroying the sacred lands of the Hopi. We organized a group to stop the trucks. I was arrested for wearing sacred eagle feathers in my hat. Paul Bernal, governor of the pueblo, made my brother and me Buffalo brothers in the Buffalo clan. He told the Feds that he’d given me the eagle feathers as part of a ceremony. They stopped hassling me.

DDWhat was your relationship with the Native Americans at the pueblo?

DHI always had a good relationship with them. Many helped me restore the House; they originally built it. There were definitely clashes between Native Americans and hippies when I first arrived, but some of that got resolved over time.

DDLet’s talk about your involvement with visual art. You had some arts education early on.

DHI did. My first teacher, when I was about five, was a Rocky Mountain watercolorist who lived in Dodge City. After we moved to Kansas City, I’d go to the Kansas City Art Institute for kids’ programs on Saturdays from ten until five in the afternoon. We’d do art things all day, lots of life drawing. There were movie theaters in both places; I ended up going a lot.

DDYou’ve talked about film being the great consciousness-changer. Still, you always gravitated to visual art and artists.

DHI met Walter Hopps and Wallace Berman, George Herms, Bob Alexander, and Ed Kienholz around 1955 at Hopps’s place on Sawtelle Boulevard, where Stone Brothers Printing set up shop. There was this actor, an older man living above the Greyhound station in Hollywood, who dressed in a Confederate Army general’s outfit and recited Shakespeare with a heavy accent [laughs]. James Dean thought he was the greatest. He had a poetry reading at Stone Brothers so I went there with Dean. That’s how I first met the group. Dean died shortly thereafter.

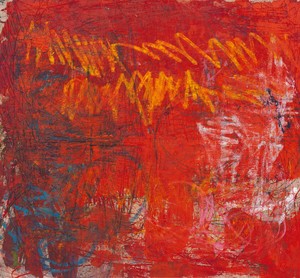

DDYou started painting around this time. Most of the early work, gestural abstractions, was destroyed in the Bel Air fire, but painting remained an integral part of your creative stream.

DHContracting with Warner Brothers at the age of eighteen allowed me to live a cultural life. Acting was sort of a free ride to be able to paint, write poetry, and be what a middle-class farm boy from Kansas thinks is an artist. Marlon Brando, one of our greatest actors, said acting is a craft. To me it’s more than that; it’s another form of art.

DDYou took up photography in the early ’60s during your stint in New York City. With a 35mm Nikon, you covered the scene, on assignment or independently, taking memorable portraits of artists, musicians, and civil rights activists. What does acting have in common with photography and painting?

DH[Lee] Strasberg, my teacher in New York, said, “Acting engages all of the senses: smell, taste, sight, sound, touch.” His “Method” involved using the senses to activate emotional memories. Painting, photography, and acting are all an extension of the senses. This applies to all art, not just to acting. Painting solo is obviously different from being an actor on set. Directing a movie may be the highest art form because it encompasses all the arts: music, photography, acting, storytelling, visual sets. Whether it’s acting, painting, or taking a photograph, keeping yourself open without preconceived ideas is the best way to create.

DDTell me about the show. How did it come together?

DHThe Harwood has been asking me to do something. With the fortieth anniversary of Easy Rider, the time seemed right. I thought about doing a historical show, you know, with works by Georgia O’Keeffe, Dorothy Brett, and Andrew Dasburg, but decided to focus on five LA artists who also came to Taos and have been my friends for more than forty years.

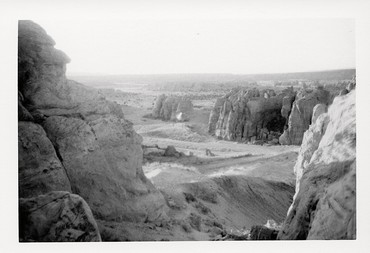

DDDave Hickey wrote in the show’s catalogue that Taos is “one of the most beautiful and chastening places in the world.”

DHTaos is a special place. It’s the second highest plateau in the world. The pueblo is one of the oldest Native American villages. And the Sangre de Cristo Mountains are one of the seven sacred mountains of the Tibetans. But it’s a tough place to live; it’s vast and violent, sometimes cruel. Some people can’t get out of here quick enough.

DDYou’re seventy-three. What’s gained with age?

DHNew anxieties. But you get rid of a lot of old ones, too. There’s comfort in what you’ve learned. You don’t have to answer to anybody; there’s nothing to prove. You also know that time is limited. You start thinking about all the things you haven’t done. I haven’t had alcohol or hard narcotics in twenty-five years. A major accomplishment. I smoke grass occasionally but I went ten years without anything. I’m much clearer now, more peaceful. There was a time when everyone wanted me to be the characters I played. I was never any of those. I wasn’t Billy in Easy Rider or the photojournalist in Apocalypse Now. And yet people sort of expected that behavior. When I drank, I gave it to them [laughs]. They just needed to get out of the way. It was a drag.

DDWhat if you hadn’t been in the movie industry, where one’s identity is a moving target?

DHHow would I have made a living? What would I have done? Sell pencils? Dig ditches? Fry hamburgers? We wouldn’t be here now if I hadn’t been an actor. I’ve directed a few films but I’ve made my living as an actor in more than 150. That’s the way I did it. There were times when I couldn’t get work. That’s when I painted and took photographs. After I made Easy Rider I decided to direct movies and stopped taking stills. That was a mistake. But it all worked out.

1The exhibition was Hopper at the Harwood, L.A. to Taos: 40 Years of Friendship. It ran from May 8 to September 20, 2009, and is documented by a modest catalogue with an essay by Dave Hickey.

2Douglas Dreishpoon and Dennis Hopper at the Harwood Museum of Art, Taos, New Mexico, May 3, 2009. Heartfelt thanks to Alexandra Benjamin, my touchstone in Taos between 2000 and 2009, when we conducted the forty-four interviews that now, videotaped and transcribed, constitute the Oral History Project at the Beatrice Mandelman and Louis Ribak Collection (MSS 1002), Center for Southwest Research and Special Collections, University of New Mexico Libraries, Albuquerque, New Mexico.

3George Herms, “Twine,” in Dennis Hopper: A System of Moments (Ostfildern-Ruit, Germany: Hatje Cantz, 2001), p. 131.

4Walter Hopps, “Out of the Sixties,” in Dennis Hopper: Out of the Sixties (Pasadena, CA: Twelvetrees Press, 1988), n.p.

5This introduction appeared in Art in America in September 2010, and is reprinted here with minor additions by the author.

6Questions remain about the extent of Terry Southern’s contribution to Easy Rider. He apparently wrote several early drafts of the screenplay, but during the film’s production and postproduction, many of his ideas, particularly for the New Orleans sequences, were cut.

7The character of Jack Nicholson’s small-town lawyer was originally written for Southern’s friend Rip Torn, who purportedly dropped out of the project after an altercation with Hopper in a New York restaurant.

Artwork © Dennis Hopper, courtesy Hopper Art Trust