James Lawrence is a critic and historian of postwar and contemporary art. He is a frequent contributor to the Burlington Magazine and his writings appear in many gallery and museum publications around the world. Photo: William Davie

In the spring of 1888, Vincent van Gogh took a brief trip from Arles to the nearby seaside town of Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer. He hoped that trip would reinvigorate his graphic style and loosen constraints of technique that dampened spontaneity. He made several fine pen-and-ink studies there, including Two Cottages at Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer (1888). There are hints of Japonisme, then in vogue, in van Gogh’s technique with his reed pen: brisk hatching and dense dabs of ink conjure up foliage and roofs thatched with grass. Two Cottages preserves the spontaneity of its execution, the kind of present-tense and inconclusive rendering that can make a work by a long-dead artist seem urgent. When van Gogh sent some drawings to his brother Theo a few days later, he held this one back as a possible source for a painting in oil. No such painting followed. The drawing held on to its unrealized potential for nearly seventy-five years, passing from heirs to collectors before Eli and Edythe Broad acquired it at auction in 1972. It was their first major acquisition, and the genesis of a private collection that has since grown to institutional proportions.

There are several ways to present what followed. A story about collecting might describe a path from two cottages in the South of France to the capacious, innovative museum in downtown Los Angeles that Diller Scofidio + Renfro designed to house the Broad Collection. A story about cultural influence might stress a process of acorn-to-oak flourishing that spans a little more than maximum human longevity and continues with the Broad’s unusually active program of loans to other institutions. A more personal account might dramatize the poignancy of attachment and loss, or at least of crisis and decision: the Broads affirmed their commitment to the art of their own time in 1983, when they traded the van Gogh drawing for a 1954 Red Painting by Robert Rauschenberg; the van Gogh drawing is now at the Morgan Library & Museum, New York. Or perhaps we might tell a different kind of story that notes the human figure in the doorway of one of van Gogh’s cottages, and treats the drawing as an early hint of the social focus that characterizes the Broad Collection. Each of these stories would be true, but not the whole truth. Collections of art, like the history of art in general, are compendia from which we can assemble stories. The most viable stories gain traction until they seem to be the way things were, are, and will remain.

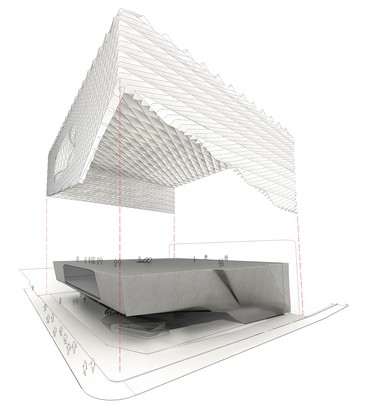

Perhaps the best place to start is on an escalator in the museum. Visitors ascend from the lobby to the collection galleries on the third floor by passing through the “vault,” a concrete-and-plaster mass that contains offices, workshop space, and collection storage. The vault is inescapable: visitors pass through it to get to the collection galleries, and walk on top of it once they are there. Visitors walking down the stairs can see glimpses of works in storage. The shell of the building, the “veil,” envelops the vault and admits filtered light that changes subtly in the collection galleries as time passes. The layout is effective in serving the interests of visitors and institution alike. It is also an enticing metaphor for two complementary states of artistic communication: the avowedly public display that gradually reveals a cogent story, and the sequestered, glimpsed repository of meaning awaiting attention and activation.

Nearly a third of the Broad’s exhibition space is on the first floor, in galleries reserved for traveling and temporary shows. The current exhibition there, A Journey That Wasn’t, is drawn entirely from the permanent collection. The show takes its title from a film by Pierre Huyghe, from 2005, that purports to record an expedition to the Antarctic in search of a rare albino penguin. In that film, sequences of majestic and brutal subzero conditions yield periodically to scenes from a performance on the ice rink in New York’s Central Park, complete with an animatronic penguin and a musical score commissioned for the event. The essentially unreliable nature of the narrative—undermined from the outset by a title that hints at fictitious treatment—conspires with the cinematography and editing to wrest poetry from prose. Documentary credibility yields to fertile doubt. Discontinuities of time and place give ambiguity an ethos. Refusal to confirm or deny becomes an aesthetic sensibility.

The exhibition to which Huyghe’s film gives its name is primarily concerned with various approaches that artists take to the problems and conditions of time’s passage. In some respects that is a limitless remit, for the passage of time is an irreducible condition. There is surely no work of art that does not display, record, embody, or engender one or another variety of temporal richness. The Broad’s show, in which each exhibit is primarily or exclusively figurative, tacitly restricts itself to a sense of time with a social aspect. Figuration calls for what might best be called “narrative time,” or “public time”—a sense of time held in common among a work’s viewers, much as the conventions that make a figure legible are held in common. This is also the sense of time that governs public exhibitions, accounts of art-historical development, and the conversations through which we discuss our experiences of art. It differs from the sense of time that we might discern as we stand before an expansive painting by Barnett Newman, for example, or as we walk through an undulating sculpture by Richard Serra. That sense of time is deeply personal, inseparable from our sense of self, and—crucially—resistant to narrative.

As vehicles for meaning, works of art are always unfinished, imperfect: informed by the past, persistently and physically in the present, and oriented toward the future.

James Lawrence

Narrative conditions favor shape, direction, and boundaries. Narrative time requires a sense of difference, of comparisons and contrasts that can reveal a particular current within the boundless temporal ocean. Perhaps an artist finds evocations of mortality in the mundane, whether depicted through the iconography of Netherlandish still lifes; in the stark white characters setting out the date in each painting in On Kawara’s Today series (1966–2014); or in the scale that makes Ron Mueck’s diminutive, elderly Seated Woman (1999–2000) so poignantly slight in the exhibition at the Broad. Another artist might exploit the capacity of art to defy or modify time. Six “typologies” of water towers by Bernd and Hilla Becher, all from 1972, share a gallery with photographs by Gregory Crewdson of the Rome film studio Cinecittà (2009). The Bechers photographed industrial structures in overcast conditions to suppress shadows, bolstering homogeneity and distilling several times and places into arrays that invite careful looking. Crewdson’s photographs of Cinecittà show film sets in disuse at a moment of economic uncertainty: hiatus in the guise of ruination.

That kind of layering, with different modes of time on display simultaneously, is readily available to artists not only because their works are primarily objects that invite sustained examination, but also because we do not examine those works with innocent eyes. Artists, collectors, curators, critics, historians, and viewers all carry with them assumptions about how and where a given work might fit—or, occasionally, refuse to fit—into their understanding of art. Whatever a work of art might try to tell us about the world, it almost certainly also tells us something about the history, definition, or purposes of artistic creativity. Paul Pfeiffer’s video piece Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion (2001) shows three looped sequences of a basketball slam-dunk contest in which the figure of the player has been digitally erased. The title of the work refers directly, and its format indirectly, to the renowned triptych that Francis Bacon painted in 1944. Neither Pfeiffer nor Bacon offers straightforward Christian iconography. Each, however, found in the theme of crucifixion a set of conventions that isolates and elevates moments of human profundity—particularly in relation to physical extremes, whether of triumph or, in Bacon’s case, of cruelty.

Pfeiffer’s effaced video loops offer elusive mysteries; Bacon’s figures seem persistently in extremis. In each case, much of the power comes from the connotations of types and precursors. Every moment in art comes with a backstory. Works of art construct their own immediate, local conditions of time, even as they contain passageways to other works with their own self-contained temporal fields. Exhibitions, and collections that can generate them, reconfigure those connections in physical ways that verbal and literary narratives cannot emulate. When art is seen—and particularly when an exhibition prompts viewers toward a mode of dedicated looking—complex networks of associations become active. More important, they become apparent and even tangible.

Andreas Gursky’s series F1 Boxenstopp I–IV (2007) is particularly rich in such associations. These imposing prints capture moments of almost choreographed technical complexity—against-the-clock repairs and renewals in pit stops during Formula One motor races—but present those moments with an air of calm that belongs less to the principle of the frozen photographic moment than to an ethos of composed grandeur. Gursky compiled several photographic instances into coherent digitally edited scenes, much as a record producer may mix several isolated and adjusted performances into a track that sounds like a group or ensemble performing together. Familiarity with the habits of viewing appropriate to a range of material—high-level commercial photography, cinema in the era of digital effects, fresco cycles—leads us to accept, and then scrutinize, visual anomalies in Gursky’s prints. Discrepancies of light and shadow, stringently consistent composition across the four prints, and a surfeit of legibility all lift the veil of split-second reality and expose the painstakingly assembled simulacrum beneath.

It might be sufficient to treat the result as a supreme demonstration of skill with the tools currently available to a photographer, or as a revelation of the gap between the appearance of reality and its true constitution. The temporal dissonances in the prints support such attitudes, which are perfectly valid. In the context of an exhibition and a collection, however—and therefore of whatever special realm art inhabits and constructs—those dissonances also point to a tradition that enhances the language of Gursky’s compositions. The intermingled figures of pit crews in team uniforms might call to mind martial figures from history paintings or Hellenistic friezes. The composition of each scene, with two balanced and self-contained groups in the foreground and an array of elevated figures in the background, calls up the same spirit of casual artifice that makes Raphael’s School of Athens (1509–11) effective: a language in which figures seem to have assembled, almost by chance, into something that renders the captured moment timeless. That ethos of persuasive composition remains valid even though the rhetorical and didactic purposes that generated it have mostly fallen into disuse. Within the context of an exhibition or a collection, it remains a viable exemplification of artistic values. In reading the results, we readily accept the existence of much more than meets the eye.

The exhibition provides viewers space in which to reflect on their own malleable experiences of time, illusion and memory.

Joanne Heyler

Presumption of semiotic intent can give even the swiftest of glances a life of its own. Ed Ruscha’s diptych Azteca/Azteca in Decline (2007) is a depiction of a glimpsed motif—a political mural that Ruscha drove past in Mexico—and a similar but hypothetical depiction of the same motif in a state of physical collapse. It is an eloquent, abbreviated, and mordant presentation of cultural fatigue, akin to Augustine’s observation “Senescit mundus,” “The world grows old.” Since February 2008, when the Azteca diptych first appeared in public at Gagosian’s Britannia Street gallery in London, the course of global events has confirmed its underlying lessons. Its theme is at least as timely now that it is on display at the Broad for the first time. Public presentation of a work generates layers of meaning and connotation—perhaps unintended, but present nonetheless—that soon become inseparable from the object itself. Long after its first appearance in public, a painting can acquire an air of wisdom about the way things are.

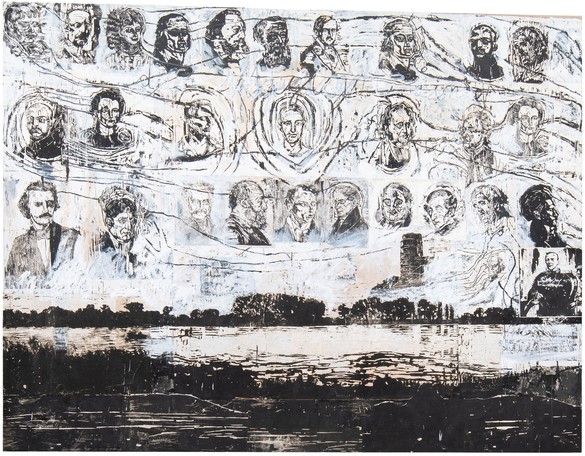

As vehicles for meaning, works of art are always unfinished, imperfect: informed by the past, persistently and physically in the present, and oriented toward the future. That situation comes with profound opportunities and grave risks. Artists who focus on history—and, in particular, on lapses in our grasp of history—are particularly attuned to the power of images to reinforce the veil of reality. Several of the artists represented in A Journey That Wasn’t address this theme. In Narratives (1993), a suite of etchings in the style of title pages from nineteenth-century slave narratives, Glenn Ligon sets précis of his own experiences in the typography and vernacular of the past in order to expose how systemic flaws in social relations remain inadequately addressed. Anselm Kiefer’s Maginot (1977–93) depicts a landscape with a fortified tower; dominating the painting is an interconnected array of woodcut portraits that came from a volume of Nazi propaganda proffering a pseudohistorical claim of cultural and racial lineage for the Third Reich. Kiefer’s reconfiguration of those portraits is only possible because that earlier configuration failed, along with the regime it served.

Figures and images operate not as autonomous individuals in an indifferent sequence but as elements that can be extracted and reconfigured within all kinds of temporal states: quiescence, recurrence, transience, persistence, or whatever best sets the terms for the story being told. Behind every veil—every story that seems to be whole and satisfactory—is a vault full of complications and contradictions, confirmations and exceptions. This can make life difficult for anyone seeking a clear narrative line. On the other hand, it holds out the promise of looser, more spontaneous approaches that suit the energetic sprawl of contemporary art. Postwar art calls for innovative storytelling. Today’s sketch might become tomorrow’s institution.

A Journey That Wasn’t, The Broad, Los Angeles, June 30, 2018–February 10, 2019