Jane DeBevoise is Chair of the Board of Directors of Asia Art Archive in Hong Kong and New York. Before moving to Hong Kong in 2002, Ms. DeBevoise was Deputy Director of the Guggenheim Museum, responsible for museum operations and exhibitions globally. She joined the museum in 1996 as project director of China: 5000 Years (1998), an exhibition of traditional and modern Chinese art.

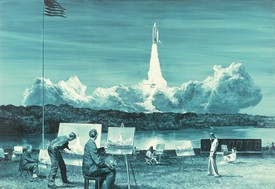

Peter Drake is a visual artist and the Provost of the New York Academy of Art, a progressive figurative and representational graduate program in New York City. Drake actively exhibits, lectures, curates, serves as a board member for the Artist’s Fellowship, Inc., and is a jurist for Base Istanbul and the XL Catlin Art Prize. In spring 2018 he cocurated Figurative Diaspora with Mark Tansey.

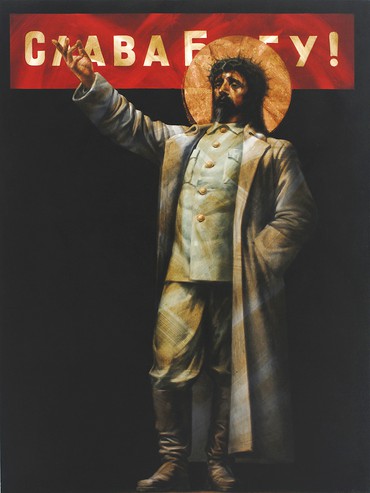

Vitaly Komar, like his creative partner Alexander Melamid, is a Moscow-born artist who emigrated to New York in 1978. Komar is one of the founders of the Sots Art movement of the 1970s and ’80s, which is considered the USSR’s answer to Pop art. Their work used the iconography and propaganda symbols of Soviet Russia to deconstruct and explode established myth.

Mark Tansey was born in 1949 in San Jose, California, and received his BA in 1972 from the Art Center College of Design, Los Angeles. He completed his graduate studies in painting from 1975 to 1978 at Hunter College, New York. Tansey’s work has been the subject of numerous solo museum exhibitions. He currently lives and works in Portsmouth, Rhode Island, and New York City. In spring 2018 he cocurated the exhibition Figurative Diaspora with Peter Drake. Photo: DPA Picture Alliance Archive/Alamy Stock Photo

Xin Wang is an art historian, curator, and art critic based in New York. Her writing has appeared in numerous exhibition catalogues and publications such as E-flux, Artforum, Rhizome, Kaleidoscope, Art in America, Flash Art, Hyperallergic, and Leap. She is currently pursuing a PhD in modern and contemporary art at the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University.

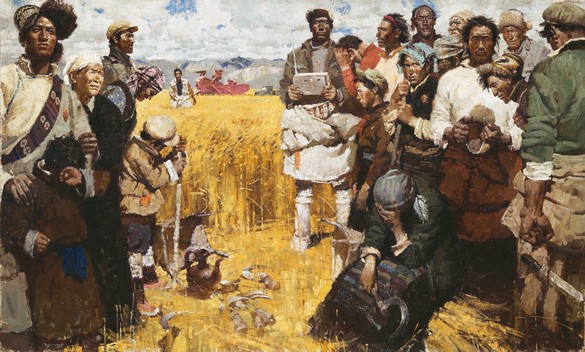

Peter Drake Figurative Diaspora, at the New York Academy of Art in early 2018, was in some ways motivated by the Transformations exhibition that Mark Tansey put together back in 1994. It was hosted in his apartment and consisted of four Chinese Socialist Realist artists: Liu Xiaodong, Chen Danqing, Yu Hong, and Ni Jun. In Figurative Diaspora there is a notion that while a visual language was marginalized in the United States and Western Europe, it was also migrating across cultures, still being preserved to a degree in the East. There, reanimated as propaganda, this language was kept alive.

Vitaly, you were the one who originally introduced Mark to these artists, so maybe you can explain how you first encountered their work.

Vitaly KomarAt that time, Alexander Melamid and I published a call to artists in Artforum magazine. We asked for proposals of what to do with Soviet communist-era monuments or Socialist monuments to Vladimir Lenin and Joseph Stalin. Russia started to destroy these monuments in the early 1990s, after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Artists from countries including Germany, China, and Russia responded to this. Our studio became a kind of meeting place.

PDWhen you saw work by the Chinese artists, did you immediately recognize traces of the education that you had received in Russia?

VKYes. Moscow represented a traditional Western academy for China in the same way that Rome did for Russian artists in the nineteenth century, when Russian artists were moving to Rome to study the Renaissance and Baroque periods.

PDMark, were you and Vitaly friends at that point?

Mark TanseyYes, we had met. I very much admired Komar and Melamid’s work and how they had internalized critical content in the Socialist Realist form.

PD Were you ever in a studio of theirs at the time?

MTThe first time I visited their studio was for one of the evening meetings Vitaly mentioned earlier. That’s where I first saw slides of Chen Danqing’s pictures and was introduced to him.

PD Danqing was living in the States for about twenty years, wasn’t he?

Xin WangHe came in 1982.

MTI remember a very striking painting by Danqing, of a field worker listening to a radio announce the death of Chairman Mao. It struck me.

Jane DeBevoiseIt’s an interesting early work of his that was shown at the Guggenheim Museum in 1998 in the exhibition A Century in Crisis: Modernity and Tradition in the Art of Twentieth-Century China.

MT I was intrigued by the idea of presenting the unpresentable, of visualizing the auditory. That goes beyond realism, it gets to realization, it’s where things come together.

PDIn your essay for the Transformations booklet, you said, “Chen’s work served as an introduction to me to the works of Liu Xiaodong, Yu Hong, and Ni Jun. And this transformational edge in his work led me to appreciate the importance of understanding their work in terms of extending temporal transformations of their culture rather than the narrow temporal postures of mine.” You were seeing it through a very particular point of view and it took you a while to adjust.

MTIt was common at that time to view contemporary art as existing in a singular, formal present. But apprehending the art of Chen Danqing or Komar and Melamid involved multiple times, multiple styles, and multiple relations between form and content.

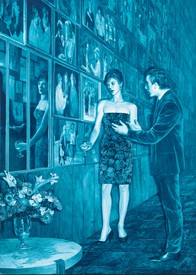

PDMark, I remember going to that show in your apartment and needing you to guide me on understanding why Yu Hong’s work was progressive because when I saw it, I thought it was just pictures of women. There was nothing about it that struck me as progressive until you put it in the context of Socialist Realist work, and then suddenly it felt extremely unusual but also refreshing, even potentially dangerous.

MTHer painting involved self-representation with a sensitive exuberance that was well beyond the agenda of Socialist Realism.

PDXin, do you know if the Chinese artists were puzzled by the American reactions to their work? I’ve heard that Chen Danqing was disappointed that the level of success he had achieved in China was so different from what he was achieving in America.

XWI wouldn’t even say he had an American reception, because there was a lack of any mainstream recognition of these artists at the time, before contemporary Chinese art started appearing in major museum exhibitions in the 1990s and subsequently as an art-market phenomenon in the mid-2000s. I don’t know what kind of feedback they got from the Transformations exhibition because that was a more intimate crowd of people who probably understood them on some level. After moving back to China, Chen Danqing published several extremely popular memoirs and essays about his time in New York, and one of these chapters was dedicated to his friendship with Mark. In this essay and others, he wrote candidly about his frustrations but also offered insightful observations about anachronisms of the New York art world, its hierarchies, and how it functioned to distinguish the “mainstream” and the peripheral practices—a category as much stylistic and temporal as historical. He was so amazed that Mark took an interest in the realist works by him and other Chinese artists and offered to reflect on their practices in an exhibition context.

PDYu Hong and Liu Xiaodong have had phenomenal success as artists. Was any part of that due to Transformations? Did a kind of bump happen afterward?

JDBYu Hong and Liu Xiaodong’s acceptance and celebration have grown significantly since the 1990s, but I feel their audience is still mostly Chinese. Mainland Chinese are wealthier than they were in the 1990s, and some have embraced these academically trained artists, particularly those who work with fairly anodyne subject matter—beautiful women, for example, or nostalgic scenes of an old Shanghai. But Liu Xiaodong is different; he often works with dystopic Beijing scenes—gritty city streets and displaced people. His painting skills are so good, it would be hard for Western and Chinese audiences not to take note, but even so, in general I’d say he’s not as widely recognized in the West as he is in China.

PDEven though he’s represented by a powerful American gallery, his audience is still mostly Chinese based.

JDBYes, that’s my feeling. The big change in visibility around these artists—at least in the last ten to fifteen years, and particularly for those who retain a closer connection to the Socialist Realist tradition—is that Chinese audiences have grown significantly. And now these audiences not only have the means to collect, they also understand the grammar and the tradition. They see where it’s coming from. They respect the academic training and recognize the controversial aspects of what the artists are doing to disturb or subvert it. They see the critique, while Westerners disregard it or don’t understand the context from which it emerges. I suspect that in the ’80s and ’90s, when these artists arrived in New York, some of them might have felt somewhat frustrated, as many had already been highly recognized in China. That may have been discouraging, but in some ways it was good because many went back to China and did great things there. For example, Ai Weiwei was more or less working in obscurity when he lived in New York in the ’80s. It wasn’t until he went back to China in the ’90s that his career as an artist and instigator began to take off.

VKWhen I came to the United States, I tried to understand the echoes of the past, the realistic and academic art in the West. In Russia during the first years of the revolution an academic system of education was destroyed as a bourgeois tradition. It was rebuilt in the beginning of the ’30s. Simultaneously, Germany established a totalitarian academy of art. The Bauhaus was destroyed and instead National Socialists started to rebuild the tradition of “the hero.”

I understood the history of twentieth-century art as not just the history of Cubism, abstract art, and Abstract Expressionism but also of totalitarian art, which was occurring in Spain and Italy as well. Chinese and Tibetan art were proto-abstract geometry. Abstract Expressionism couldn’t be popular [in China] because Chinese hieroglyphs are by concept, by origin, the same as Abstract Expressionism. That’s why Chinese artists themselves were attracted by the realistic depiction of nature, and to poetry, and sometimes combined the two. That’s one way to understand why the tradition of realism was so popular and is still popular in China.

In Russia, there was a different reason for the explosion of academic art. The height of Russian art was during the end of nineteenth-century symbolism. It was famous, even in Europe. The idea of depicting another, imaginary world was reflected in the communist idea of building another world, a new world, an ideal society on this earth. It was a great illusion, which ended tragically in Russia. It was a tragic lesson to all humanity because sometimes it’s very dangerous to turn a fairy tale into reality.

The idea of depicting another, imaginary world was reflected in the communist idea of building another world, a new world, an ideal society on this earth. It was a great illusion . . .

Vitaly Komar

PDPart of what you’re known for, especially when you were collaborating with Alexander, was an ironic repurposing of the grammar of Soviet Socialist Realism. That’s been a thread through your work—using this language, repurposing tropes from the ’50s, from the film world, from illustration, from art history, and turning them on their heads. Mark, was that something you found in the work by the Chinese artists?

MTDanqing’s work in particular involved cross-cultural juxtaposing and repurposing of images of different times. What the artists had in common was an emerging sense of self-reflection and self-authorship.

PDBut always with authenticity, right? They weren’t indulging in some of the notions of a bankrupted culture that a lot of ’80s postmodern artists were.

MTThere was a vitality that stood out against the narrow presence of the ’80s commodity critique. I don’t know how to put it simply. I noticed a quality, a depth, a complexity in the work. I saw that in Komar and Melamid’s work as well as in the Chinese artists’ work.

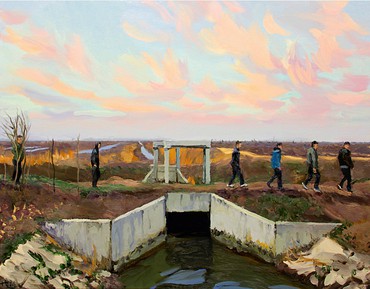

PDFrom the New York Academy of Art’s point of view, our interest in Figurative Diaspora is this notion that a certain language, while it was marginalized in the US and Western Europe, could be migrating across cultures, being preserved and reenlivened, even though it was being repurposed for propaganda. This language was kept alive, which explains why artists from the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing have a phenomenal skill set. You look through a book of drawings of student work and you can just be blown away by the facility. I don’t know if you could go to any academy in America and find that level of talent. It has disappeared inside of two generations.

MTWe have an American history of the avant-garde, where abstraction supplanted representation. In the late 1970s and early ’80s there was a return to figuration, but even so, it’s fascinating to see other things happening in different cultures, to see the flows of official and nonofficial and academic versus avant-garde.

VKEarly on in postmodernism, at the beginning of the ’80s, the New York Times ran the headline “Today’s Avant-Garde Artists Have Lost the Power to Shock,” above an article by Hilton Kramer. The avant-garde had lost the element of surprise.

MTYes, it had become academic.

PDIt became mainstream.

JDBThe continuation of figuration and realism and their pervasiveness outside the Euro-American sphere is something that fascinates me. It proposes a certain kind of resistance to the mainstream as we have developed it, this hegemonic view of what is and what is not art. There is a Euro-American modernism, and then there is modernity, and then there is the socialist modernity. We don’t seem to adequately acknowledge that modernity comes in different packages, and that socialist modernity is just as relevant to world culture as Euro-American modernity yet is almost never embraced, almost never validated in Euro-American institutions. Whatever we think about totalitarianism, there is something within the wreckage of Mao’s socialism that still resonates in the minds and hearts of many artists in China. Acknowledging that may make artwork by people like Yu Hong or Liu Xiaodong more legible and clarify their desire to continue to communicate broadly. It may be interesting to think through realism and figuration in a broader, more ideological sense, as well as an

artistic sense.

PDPart of that must be how the avant-garde positioned itself in the culture, wanting to be exclusive and not for the masses. To a certain degree there was a kind of intellectual elitism that was not interested in speaking to the average person. The notion of communication to a broader audience, whether it’s through Socialist Realism or any other form of realism, is sort of antithetical to the avant-garde.

That’s the vitality of the figurative, you’re not re-presenting anything literally—you’re re-presenting, metaphorically.

Mark Tansey

VKIn Russia, the avant-garde ended in the late 1920s, when it lost the ability to attract official power within the government. From the beginning, they’d said the masses did not understand the abstract art of Kazimir Malevich and the others. At a certain point, even Malevich started to paint realistically.

PDDe Chirico changes also, a little earlier.

VKThere was a tendency to change in search of the “new.” Paradoxically, realism became new for a short time at the end of the ’20s, beginning of the ’30s. Nowadays we have an entirely new situation, where all kinds of art coexist. Just take a walk in Chelsea and you will see video art, realist art, photographs, abstract expressionism, abstract geometry, surrealism, etc. That means our criteria of what’s good in art has opened up. We have become tolerant of many contradictions.

PDBut that also creates a critical crisis.

VKSometimes crisis is the period before you go back to health.

PDJane, it’s interesting that in contemporary Chinese art, particularly with the artists who were in Transformations, there remains a strong attachment to realism. Where does this attachment come from?

JDBWe just had a show of contemporary Chinese art at the Guggenheim Museum in New York. It’s interesting to note that the curators of this show made a choice to omit painting, at least for the most part. Among the paintings that were included were works by Yu Hong, Liu Xiaodong, and a few others, but the core of the exhibition relied on other media—installation, performance, and video. We should remember, however, that many of the artists in that exhibition started out as painters and have retained the skills you mentioned. They are academically trained artists from the Central Academy in Beijing, or the China Academy of Art in Hangzhou, for instance. Behind the conceptual art that the Guggenheim curators decided to present are amazing realist painting-and-drawing skills.

After June 4, 1989, and through much of the 1990s in China, public museums, which were almost entirely state run, were prohibited from displaying so-called avant-garde art, exemplified by much of the work that you saw at the Guggenheim. Artists like Yu Hong and Liu Xiaodong, both students and young teachers at the Central Academy in the late 1980s and ’90s, may have wanted to continue to exhibit their work publicly, to continue their conversation with the public. In one of his essays Vitaly used the term “official conceptualism,” which I thought was lovely. Is that what we have here?

PDWasn’t it also true that Yu Hong was taking some chances with her own career?

JDBYes, but she stayed with a more traditional-looking vocabulary and she perfected it. As did Liu Xiaodong. They were truth-tellers in the sense that they were showing a Beijing that was not bright, shiny, and red, required characteristics of politically acceptable art during the strident Maoist years. That willingness to tell the truth was controversial within a mainstream context. For example, one work by Liu Xiaodong in the recent Guggenheim show showed two boys, liúmáng or hoodlums, burning a rat—marginalized, unemployed guys hanging around, doing nothing, being bored, and burning a rat. That was the flip side of the new economy that was beginning to surge. People were going to be left behind. Liu Xiaodong communicated this new reality in a language that was at once legible and unsettling.

They were truth-tellers in the sense that they were showing a Beijing that was not bright, shiny, and red, required characteristics of politically acceptable art during the strident Maoist years.

Mark Tansey

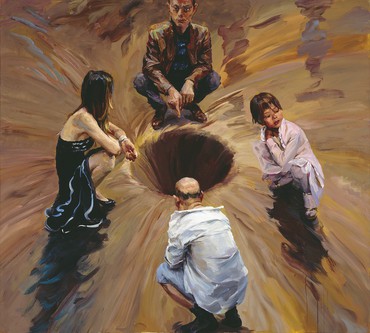

PDThat’s one of the aspects I was attracted to in Lu Liang’s work too. He does these incredibly bleak pictures of ghost cities and strange vistas, on an enormous scale, you feel like you’re stepping into reality in a strange way. All the skill sets are there. He’s using everything he’s learned and deploying it to make a very dark statement. But they’re still incredibly beautiful, hauntingly so.

JDBThat duality is embedded in the work of a lot of artists who want to maintain a certain kind of visibility, or work within the system, and yet at the same time feel deeply about the social problems in China.

PDIn America, earlier generations of conceptual artists have now become deeply embedded in academic life and there seems to be little interest in technical training. It’s a very strange moment. These are people who took chances with their creative lives, saw themselves as progressive, but then institutionalized their beliefs. You go around the country now and even foundation programs are being done away with. And there’s very little room for that training in the larger art marketplace. It’s an entirely different sort of institutional culture.

XWAt the same time, it feels like a familiar story, where progressive and democratizing goals almost inevitably become institutionalized. I think what Jane has just laid out about China specifically is important because it’s not just about preserving something—a tradition or a genre—it’s also about expanding and transvaluing it into something completely different, often in response to changing times and cultural/political climates.

PDThat’s the most important thing. Part of what’s frightening about traditional atelier practice is that the drawings that come out of it frequently look very similar. But in China at the moment, you don’t actually see this salon sensibility of just repeating the past, you see really great figurative work, and it’s looking to the future. It’s taking advantage of all these linguistic skills but deploying them in ways that haven’t been seen before. It’s fascinating and exciting.

JDBIt’s interesting to consider the community of Chinese artists who came to New York around the time of Mark’s Transformations exhibition, a community that included both Ai Weiwei and Liu Xiaodong. On one hand, they came from a similar milieu and were friendly colleagues in New York, yet there’s a divide in terms of their approach toward the system. Vitaly, when people from Russia first came to the United States, did that same sense of community pervade?

VKI guess it depends on how long you stayed in New York.

Heidi ElbersVitaly, Chinese artists exhibited in Moscow when you were studying. Do you remember what kind of art was shown?

VKIt was Chinese Socialist Realism.

HEIn the ’60s?

VKIn the ’60s it was different. It was a more provocative time.

XWMark, you were very tuned in to unpacking something about these Chinese artists, and you mentioned the conceptual and perceptual in our previous conversations. That seems to be the duality where irony or ironic meanings would manifest. Interestingly enough, however, in these Chinese artists’ works, there is not the same kind of irony that you practice or subscribe to in your work.

MTI’m not sure to what degree irony overlaps with humor or satire. There is an outward aggression in humor that can be alleviated by laughter. But Vitaly had said recently that irony is “related to the idea of self-reflection.” That’s what I saw vividly, in multiple senses, in the work of the Chinese artists.

VKSometimes I feel that my self-irony is very close to self-destruction. Because in purifying yourself you’re also losing part of yourself.

PDThere’s a certain kind of disenchanted idealism that uses irony to sort of attack one’s previous faith. Mark, do you feel that the word “irony” implies a lack of faith, or a lack of authenticity?

MTIt seems inadequate to try to put a tight definition on it. Satirical artwork, humor, visualizing irony—there are relationships that are volatile, beautiful, and funny at times, but how they come together is quite explosive, an enigma.

VK“Explosive” is a good term.

PDThat’s funny, because I remember back when critics felt your art depended on one-liners, so you started to embed text in your work.

MTI realized that text as texture can become picture.

PD They didn’t see the complexity of the work. They weren’t willing to invest themselves in decoding its complexity.

MTAt that time, even though a lot of attention was certainly given to representational artists, the critique of representation had it that representational meanings were “single coded,” “single messaged,” and “totalizing.” But if you go beyond that reductive thinking it becomes apparent that there is inherent complexity in how the perceptual and the conceptual interact with the making of a representational picture. That’s the vitality of the figurative, you’re not re-presenting anything literally—you’re re-presenting, metaphorically. It’s about the interaction of seeing, thinking, and making. And when I see people doing it with verve, it’s a pleasure. It can be dangerous, satirical, ironic, critical, insightful, revelatory. . . .

VKAlso sometimes sarcastic.

MTIts many reflective modes show the adequacy of representation as a form of signification.

HEPeter and Mark, you have been working toward the Figurative Diaspora exhibition for quite a while. Can you talk about your thought process?

PDAt the start we wanted to focus on technical sophistication, but over ten or fifteen years, the proposition changed dramatically, and now it’s something more like traditional skills and contemporary discourse. The artists in both Transformations and Figurative Diaspora have made an enormous effort to acquire an incredibly difficult set of skills, and they’re trying to do something progressive, something that hasn’t been seen before. Part of what makes their work so interesting is that the language has morphed as it has moved along. Some of the tropes from Soviet Socialist Realism still show up—you’ll see figures portrayed from below, or lit with artificial light. But those devices are used in different ways now, and it feels like there’s a real connection between all three cultures.

1Jean Renoir, “An End to Nationalism,” in My Life and My Films (Boston: Da Capo Press, 2000), pp. 279–80.

Figurative Diaspora, New York Academy of Art, January 16–March 4, 2018