Derek Blasberg is a writer, fashion editor, and New York Times best-selling author. He has been with Gagosian since 2014, and is currently the executive editor of Gagosian Quarterly.

Derek BlasbergI guess the first question should be, why now? What happened that made you want to look back on your career and put pen to paper?

Sally MannTo be honest, it all happened by accident. And to be very honest, I don’t even like memoirs that much. I had never planned on writing my own. But I was asked to do the Massey Lectures in American Civilization [at Harvard University], and after a year of thought—and some anguish—I decided I would do it. Then it just became a vortex I went into.

DBHad you kept a journal? Or were there any autobiographical texts that you could turn to?

SMNo, I had stopped keeping journals a long time ago, so I was starting from scratch. I was a big letter writer, so I had those. I went up to my attic and found some things that jogged memories and I realized that I also had about a dozen of what I call dinner party stories, the sorts of little anecdotes that we all tell over and over when we’re at dinner parties. I realized that those twelve stories turned out to be my life, and they became a sort of outline. I started cobbling them together and then it became a book when I fleshed them out.

DBIn the book there is such drama; love affairs, racial tensions and even murder. Did you know all this growing up, or was it something you discovered?

SMSome of it I knew and some I discovered—or, as in the case of [my husband] Larry’s parent’s suicide, discovered the details.

DBWhat did you find?

SMWe had thought it was drugs, but then I did some detective work. When I got to the bottom of it, it was a bunch of things. Definitely there were drugs, but there was also an affair. Larry’s father was having an affair with someone named Mrs. Pritty. There had to have been a betrayal or something like that to bring Larry’s mother to take a shotgun and blow her husband’s head off—and then her own. There was also debt; there were so many factors.

DBWhen I was looking at the book I started to wonder if there was also this much complication in my family, but maybe I didn’t know it. Do you think most families have these complexities and dramas, but some are better at hiding it?

SMYou’re asking if everyone has a mad woman in their attic? And the answer is yes, probably. I think when most people are little and their parents are talking about relatives, we don’t listen. Like I used to hear my mother talk about Uncle Skip, and I didn’t pay any attention. But before she died, she wrote her life story, which of course I didn’t read until she was dead—and my eyes were popping out on their stalks! I was going “This is wild!” She had all these things happen to her, all these stories—and where is she now, damn it? How can I ask her?

I think place is important, and I’m fortunate to be grounded in a place as phenomenally beautiful as this. I’d be crazy not to want to stay. It really is the nucleus of all my creative process.

Sally Mann

DBI think the title of the book—Hold Still—is wonderful.

SMIt would be embarrassing to show you, but I have a whole file of possible book names. I must have come up with 150. The first one I came up with was “Cracker Jack.” It was my father’s favorite phrase of approbation for something that was truly superb. Of course, now it’s known for that candy popcorn. But when I came up with “Hold Still,” it was one of those heart-stopping moments. Right away, I knew it was perfect.

DBWas there a therapeutic element to this process?

SMYes, I found that. It was definitely cathartic. And revelatory too. There were moments I found unsettling, like when I discovered certain genetic tendencies. You can’t argue with genetics, but I think it’s human nature to not want to make the mistakes our forebears made and hope that our children don’t make the mistakes that we did.

DBYou've never left Virginia. Is that convenience or is there a bond to that part of the world?

SMMaybe fear? I went away to boarding school, I went away to college, and I went to Europe for a year. But after that, I came back and I haven’t left. All I can do is get on a train and come to New York for a few days. I think place is important, and I’m fortunate to be grounded in a place as phenomenally beautiful as this. I’d be crazy not to want to stay. It really is the nucleus of all my creative process.

DBI grew up in Missouri and I didn’t have respect for the beauty of the country until I was much older. Were you the same?

SMNo. I swear to God I knew with my first cry in the delivery room or the minute my birth-bleary eyes landed on my surroundings that this place is imperishably beautiful. It’s inarguable.

DBI know you started taking pictures young, first on your father’s camera. Was that just for fun and a hobby, or did you always think of it as an artistic expression?

SMIt was to be an artist. Well, at first I thought I wanted to be a poet, a writer. When I couldn’t decide, I started making a living as a photographer.

DBBut now with this book, you’re both.

SMYes, I guess that’s true.

DBWhat were your early pictures of?

SMMy first roll of film was scenic, landscapes I guess. And eventually my kids came into the frame.

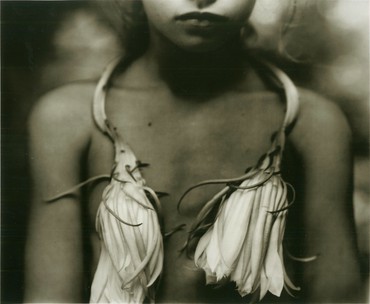

DBAnd when that happened, your career was forever altered. In 1992, your book, Immediate Family, received criticism for the relatively few nude images of your children. But what is detailed in your book, and what I think most people forget, is that you also got fan mail.

SMYes, the reactions were all over the place. There was an article in The New York Times Magazine about that book, and the magazine received a great deal of mail feedback. I separated it into three piles: good, bad, and “what the fuck?” What was gratifying is that the good and bad piles were basically equal.

DBI know you read those letters then, but do you read the comments on the Internet nowadays?

SMNo. I don’t look at them. I just couldn’t bear to go through it. I was talking to someone about it the other day, and they explained it. If someone writes a letter—if they take the time to put pen to paper—that’s a considered and measured response. But an anonymous, hurtful thought put on a comment section at the swipe of a keystroke? No.

DBI understand that rationale because once you see those comments, you can never un-see them.

SMI’ve learned something else: never read criticism.

DBI read that you didn't anticipate the mixed reactions to that book. Is that true?

SMI was completely blindsided. I was naive enough to feel that everyone saw the pictures in the same way that I did, and there wouldn’t be so many interpretations that I thought were so wildly off the mark. Of course it would be disingenuous to say that I didn’t anticipate any reaction, but I wasn’t prepared for what happened.

DBIt became quite a debate.

SMYes, it did. But I had no legal problems, I didn’t get my photos waved around by Jessie Helms in Congress. So I must say it wasn’t all that bad. It was more intellectually harmful when people said things that weren’t true.

DBI think that when someone writes a memoir they must, to a certain degree, confront their own legacy. I know this is a tough question, but what would you want your legacy to be?

SMI think it would be nice to be remembered as an artist who tried to work within the commonplace, the quotidian, and did so in a way that was revelatory and resonant. So, will people still be talking about my work in a hundred years? I don’t know. I know I can’t control my legacy. I will just be grateful if I have one.