Charlie Fox is a writer and artist who lives in London. He wrote the book of essays This Young Monster, directed a music video for Oneohtrix Point Never with Emily Schubert, and curated the twin horror shows My Head Is a Haunted House and Dracula’s Wedding. His fiction and nonfiction have appeared in Dazed, The Paris Review, and the New York Times.

I’ve always wanted to write a guide to the work of Jim Shaw. His vast and ever-mutating oeuvre is also a dense and mischievous self-enclosed world, trippy, allusive, full of wild characters—is that Alfred Hitchcock’s head hanging off a McDonald’s bag?—and extremely weird scenes: whoa, look at the dancing girls in the middle of that blizzard of confetti on the emerald staircase in Down by the Old Maelstrom (Where I Split in Two) (2022), they’ve got cue cards with the opening lines from the Book of John on them: “In the beginning was the word.” What does it mean to go down those stairs into Jim Shaw’s underworld? And what can words do with this stuff? I thought a guide might be helpful in a goofy way—Jim Shaw for Dummies—but also the work itself refers to all kinds of complicated texts: the Bible, gnostic prophecies, Philip K. Dick, and—save me, Superman!—Ayn Rand. An outrageous sprawling codex, like Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow (1973) or the annotations to Earl Sweatshirt lyrics on Genius, was always just craving to be written.

Let’s get lost in the funhouse.

AMERICA • Jim Shaw’s work is very American. This entire guide could be dedicated to American things that appear in or have had some kind of influence on his work: EC Comics, the Church of the SubGenius, Mad magazine, Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters (Shaw painted the mural on a replica of their infamous acidhead bus for the movie Heart Beat of 1980), the exotica records of Martin Denny, Detroit, Busby Berkeley musicals, the 1993 Waco siege, and much, much more.

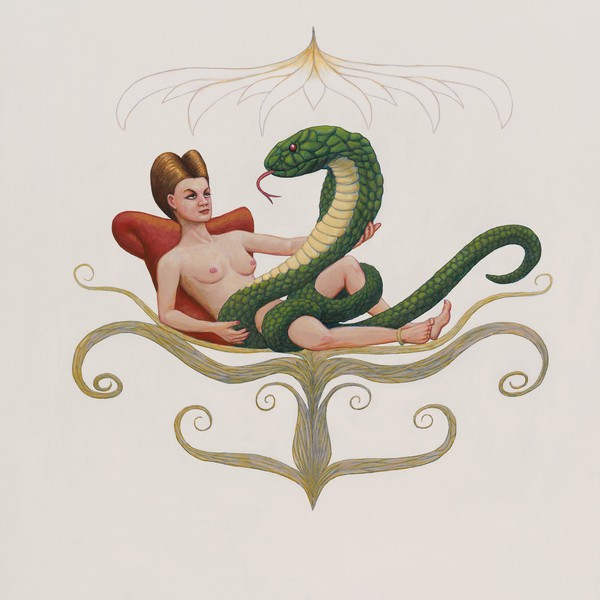

The work is also extremely American in its unashamed vastness and encyclopedic energy, recalling huge US beasts such as Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick (1851), Robert Wilson and Philip Glass’s Einstein on the Beach (1976), or the Smashing Pumpkins’ Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness (1995). Shaw’s oeuvre provides a vision of America and its multiple vexed and wild histories deep-fried by hallucinogens. Even St. George and the Dragon (2015), his rendering of a foundational myth in British history, presents itself as an American story, like Rocky versus Apollo Creed: the Stars and Stripes flutter in our good knight’s hand; the dragon is played by a hot Playboy temptress, wings replaced by a Wonder Woman red cloak. If you asked Shaw, he could decipher and illuminate all this for you, but the sheer hot and hallucinogenic mystery may be even more fun to play with. To borrow the title of another of Shaw’s works, “The great whatisit?” is often the question you’re asking when you look at his work, jaw slack, brain melting.

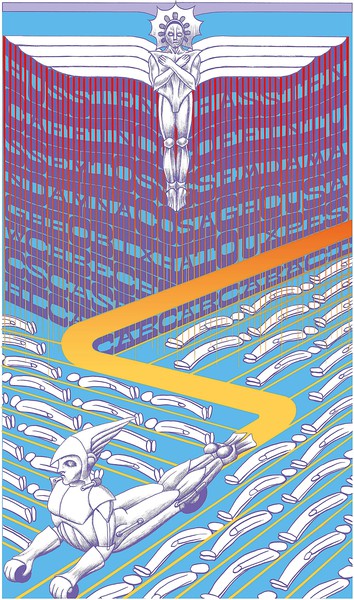

BILLY • Billy is the protagonist of Shaw’s epic My Mirage (1986–91), which, if I were wearing my Arthur C. Danto mask, I’d call the great masterpiece of postwar American art. It’s a freaky bildungsroman chronicling Billy’s coming-of-age from small-town kid to hippie wastoid to Jesus freak through the shape-shifting matrix of American art itself. Billy’s life story is told as a cute Maurice Sendak storybook—he’s dressed as a bunny rabbit and he meets the devil. Or, as gross photorealist renderings of high school yearbook photos in which all the students are deformed. Or, as Hairy Who–style brain-melting gig posters. Or, as Ed Ruscha–style paintings of text: “He drew the dirtiest thing he can think of,” laid against a monochrome backdrop.

My Mirage is also a cryptic autobiography, illustrating what Shaw was—a curious boy, a drug-blitzed far-out adolescent—and what he could have been if, like many other countercultural folk, he had felt the shimmery lure of religion waiting at the end of one too many trips. In taking self-portraiture as a deranged dressing-up game addled by pop culture, sex, and art itself, My Mirage’s closest relative might be Matthew Barney’s Cremaster Cycle (1993–2002) but ultimately it’s a monster like no other.

CONSPIRACY • Shaw keeps up an anthropological fascination with conspiracy theories, the more whacked out the better. In collaboration with Gagosian and New York’s Metrograph cinema in 2021, he curated a program of conspiracy-minded films, including John Carpenter’s They Live (1988; of course), Total Recall (1990), and Winter Kills (1979), a satirical comedy about the assassination of JFK that was mysteriously denied wide release despite rave reviews and big ticket sales. As Shaw pointed out in a note accompanying the program, all were movies “about the quest for truth and how it can become a complicated thing.”

Much like Shaw’s art, part of what’s amazing and fascinating about conspiracy theories, strictly as manifestations of the human mind rather than any kind of, uh, “truth,” is their tendency toward outrageously baroque complication, storytelling gone bonkers, up into the stratosphere, down into the darkness, running into the chilly mitts of CIA sharpshooters and politicians who are secretly lizards. By the way, I’m not saying that all of Shaw’s work contains some kind of hidden truth, that it will form a strange glowing orb in the event of his death, or that he appears as an extra in a biopic of Tom of Finland from 2018 listed on IMDb. Or am I?

DREAMS • Shaw’s Dream Drawings (1992–99) are maybe the closest you can get to the experience of inhabiting someone else’s brain. Shaw spent a couple of years making deadpan drawings of whatever he’d dreamt of the night before, and the results are pretty wild. The titles by themselves are hypercondensed short stories: “A comic book by Tom of Finland in his early heterosexual days about a disaffected college student.” Like everybody else, Shaw’s got a pornographer in his unconscious and whoever they are, they’re into all kinds of weird stuff. Obsessive? Duh, of course. That’s what gives Shaw’s work so much energy. In an Artnet interview he said re: his hero Hieronymus Bosch, “I admire people who stick at it no matter what.”

EFFECTS • For many years, Shaw subsidized his art by working in Hollywood’s special-effects industry. Alongside early experiments with CGI, this job entailed a lot of sculpting, drawing, and painting, all of which adds up to a kind of phantom career running in parallel to his own. Batman and Superman with their identities in trippy flux may be good touchstones here. Are there two Jim Shaws, one commercial/industrial and the other not? Or is it all the same? As he told the Quarterly’s Natasha Stagg in 2021, while moonlighting in Hollywood Shaw designed “the alien fur and spaceships for Earth Girls Are Easy [1988],” some stuff for A Nightmare on Elm Street 4 (The Dream Master) (1988), “high-end FX commercials,” and “a scene in The Abyss” (1989). Trippiest of all, straight out of art school in the 1970s he got a job drawing “the dream of a god” for Terrence Malick’s opus The Tree of Life, a movie that wouldn’t materialize fully formed until 2011. I’ve looked into it and the god in question may have been “an underwater minotaur.”

It’s not hard to see how all this activity would have fed Shaw’s brain, a mutually sustaining parasitic loop between himself and Hollywood that in turn would supply ideas for his own work. The craft and execution of Shaw’s work are also very Hollywood. Look at the manic rubber-nosed Nixon popping out of the chaotic Fritz the Cat–esque street scene backdrop in Labyrinth: I Dreamt I Was Taller Than Jonathan Borofsky (2012), or the girls dancing in his film The Rinse Cycle (2012). It’s not lo-fi or sloppy, it’s professional, the real deal, and yet still . . . the stuff of dreams.

FRAZZLEDRIP • “Frazzledrip” is a word coined by the nefarious QAnon conspiracy network, which claims it was the title of a folder on the laptop containing Anthony Weiner’s personal video footage of the phantasmagorical Pizzagate scandal—mainly Hillary Clinton and her 2016 campaign manager Huma Abedin attacking a child and drinking its blood in a satanic ritual at a New York pizza joint. Shaw has purloined “frazzledrip” from QAnon as an affective term for the adrenaline rush excited by any kind of lurid entertainment. “For me,” as Shaw told Stagg, “and for anybody that’s entranced by conspiracy movies, by true crime podcasts, by endless depressing documentary series about horrible events that took place at some boys’ school sometime in the ’70s, it’s stimulating the frazzledrip in our brains.”

GRANT, CARY • The suave leading man from Hollywood’s golden age appears in one of Shaw’s paintings, Cary Grant (2022), a spooky remix of the famous moment from Hitchcock’s classic thriller North by Northwest (1959) where the star attempts to outrun a plane that’s chasing him. Except in Shaw’s version he’s running away from an enormous version of his own face, which is grinning presidential-portrait style and is itself acting as the surface for a painted sky inhabited by another cheerful Cary, this one whooshing above the clouds in a kind of Aztec jet pack. Before you can even try to return to a normal altitude, you notice the rivers of viscera and disembodied baby legs that make his tanned cheeks look all flayed. Thinking about Shaw while this huge painting looms over you, you might want to ask the same question Hitch did when that wicked cockatoo bit him in the original trailer for The Birds (1963): “Oh . . . now why would he do a thing like that?” Maybe it was because, pre–Timothy Leary, Grant was a major evangelist for LSD, undertaking tons of trips as part of his psychotherapeutic regime. Here we have Cary on a bad trip. Or maybe Shaw just watched North by Northwest too many times.

HORROR • Asked by Dazed in 2015 “What is the scariest monster of all time?,” Shaw responded, “All of us humans.” Which is kind of haunting.

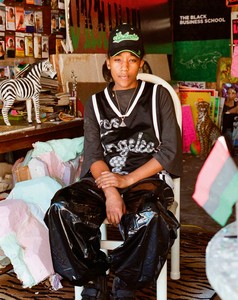

INVENTORY • Shaw is a longtime denizen of thrift stores all across America, eternally in search of the weirdest eruptions from the American psyche, the morbid, kitsch, goofy, and twisted. This magpie habit famously manifests in his vast collection Thrift Store Paintings. As he told Dazed in that 2015 interview, ahead of a few of them appearing in an exhibition at the Barbican in London, Magnificent Obsessions: The Artist as Collector, it all began when he was a teen in the late ’60s: “One day I came across a four-by-six-foot Masonite panel with a crude painting of a Breck shampoo girl, which was pretty extreme. It got me interested in the potentials.”

JOHN F. KENNEDY JR. • The assassination of JFK is not where conspiracy theories began to be a thing. I don’t know what was: Jack the Ripper? Pandora’s Box? Or maybe Eve and the snake? But Dallas on November 22, 1963, is where they went into overdrive. For more read Don DeLillo’s Libra (1988). The 2018 show Everything Is Connected: Art and Conspiracy at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, contained Shaw’s doctored stills from the notorious Zapruder film capturing JFK’s assassination, but in this case placing aliens at the scene. The truth is out there. Where have we heard that before? Also, why did the Fox network cancel the JFK/Oswald–haunted X-Files spin-off The Lone Gunmen (2001)? What do they know that you don’t?

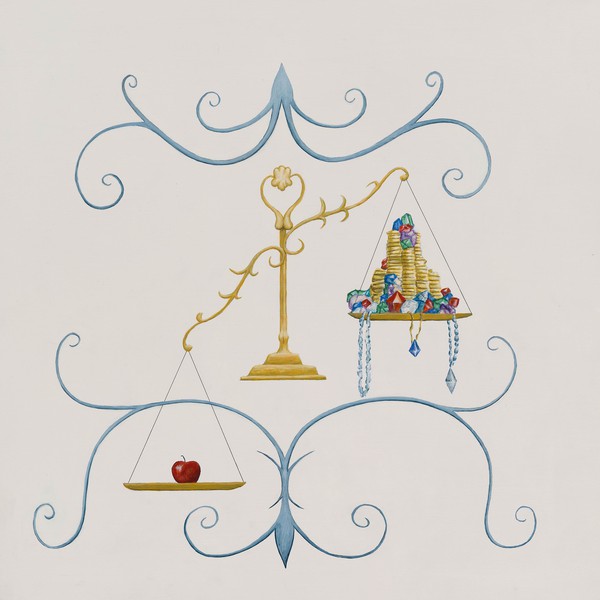

KING COTTON • King Cotton (2015) is one of Shaw’s scariest paintings. A gleeful tyrant complete with crown lords over a pile of gold. He happens to be made out of cotton and there’s a green mechanical elf at his side. At the edge of the scene stands a Black maid holding a white child, the two of them stone-faced.

America’s darkest sin and psychic turmoil are refracted through a fairytale mirror. Slavery, of course, looms over the whole thing: not just the maid and child but the cotton, the cruel master, and the heap of gold. The terrible legacy is of course still here: nature ransacked, the exploitation of the poor in the service of the superrich, dirty lucre, all of it embodied in the wicked figure of King Cotton, who joins a mighty American pantheon of imaginary (and all-too-real) evil capitalist ogres: Mr. Burns from The Simpsons (1989– ), Mr. Potter in Frank Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life (1946), Donald Trump.

Plenty of trickster kings reign over or lurk in Shaw’s paintings: L. Ron Hubbard, the Great and Powerful Oz, the 45th US president, and, of course, God in all His forms.

LA • Shaw and his pal Mike Kelley headed out for LA from Detroit in 1976, Kelley in a Ford Pinto and Shaw in his trusty AMC Gremlin. Detroit’s deep industrial decline was kicking off, thanks to the oil crisis, and like tons of American dreamers before them, Shaw and Kelley were seduced by the fantastic possibilities out West. If you were Jim Shaw, how could you not be into it? Los Angeles is somewhere dreamt into existence, a nonstop cavalcade of the grotesque, the camp, and the ridiculous, a Fellini movie with In-N-Out Burger, surfers, and plastic surgery up the wazoo. It’s the home of film noir, Studio City, and Hollywood Babylon. Cue the demonic garbage ghoul from Mulholland Drive (2001), please! Interviewed for Kaleidoscope last year, Shaw called David Lynch “the greatest living artist, in a way.” Yup, LA’s psychogeographic impact on Shaw’s mind is obviously major.

MIKE • Back in the early 1970s, long before they were such heroic figures, Jim and Mike Kelley were just two misfit art students drawn together in Ann Arbor, Michigan. They fed on the more extreme bacteria of psychedelic culture, not to mention the toxic waste that would become punk rock—the MC5! Sun Ra! William S. Burroughs! They did Dadaist performance pieces together. They formed the legendary noise-rock band Destroy All Monsters with some pals, all of them living together in a ramshackle gothic abode that should probably be a museum now. They remained pals until Mike’s untimely death in 2012.

Maybe the greatest illustration of their friendship is the painting from Jim’s series Paperback Covers (c. 1996–2013) that depicts the two of them fucking. For the occasion, Jim’s unconscious has rented the kind of trashy motel room that Lula and Sailor might rent in David Lynch’s psychopathic romance Wild at Heart (1991), all shag carpeting and wood-paneled walls. Touchingly, they both appear in the painting as young men, Mike still the longhair who appears drooling slime in his faux-spiritualist Ectoplasm Photographs (1978–2009). The two straight men are gazing at themselves in the mirror while they do it, watching themselves getting high on each other. Collaboration in its purest sense: I mean, where does Mike end and Jim begin?

NIGHTMARES • A lot of Shaw’s works are pretty nightmarish. Another of the Paperback Covers paintings depicts a deranged clown fucking a block of wood that floats in midair, his crotch sucked right into the knotted vortex at its center. It’s like the tree fucking in Paul McCarthy’s installation The Garden (1992) given a Pennywise makeover. Colorophobes, take two Xanax and pray for a jump cut to morning.

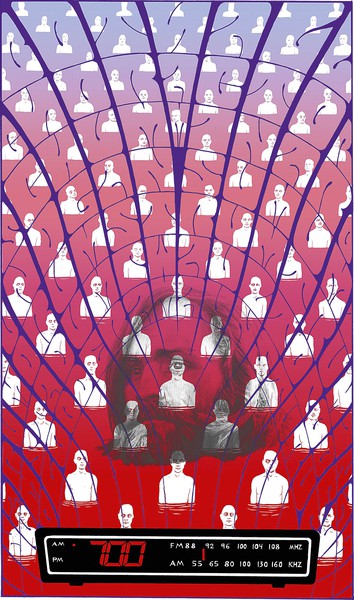

OISM • Oism is a religion founded by a proto-feminist mage in the upstate New York of the 1830s, the spawning point for later faiths (or “cults,” if you prefer) such as the Universal Friends. Or maybe it was actually created by Shaw in the 1990s as another vessel for his work. It led to Untitled (Faces in a Circle) (2009), a painting of a bunch of cheery housewife heads forming a mandala against a riot of grungy Abstract Expressionist paint-strokes. (These ladies look like they play tambourine on a Christian Science LP found in a bargain bin.) And it also led to the fantastic backdrop of D’red Dwarf, B’lack Hole (2010), with its bubblegum-pink humanoid trees and glowing pyramid topped with an all-seeing eye. Not forgetting The Rinse Cycle, a prog-rock opera and accompanying collection of videos influenced as much by Yes’s Tales from Topographic Oceans (1973) as by Wagner’s Ring Cycle (1848–74). Oism is a world within a world, an index of Shaw’s obsessions. The creepy hippie detritus, conspiracies, religion, American perversity, art, nonart, and parodies thereof: you can find it all in Oism.

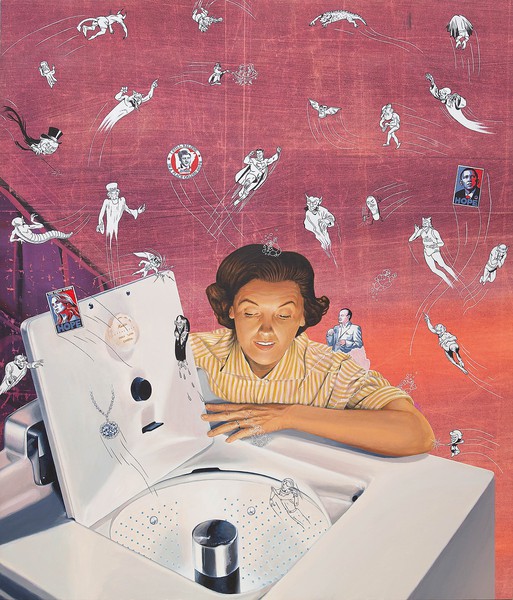

PANDORA’S BOX • I figured Pandora’s Box, from (uh oh) 2020, may be a covid-19 painting. The happy protagonist looks like a housewife from early Mad Men (2007–15), her washing machine’s drum aglow like the briefcase in Pulp Fiction (1994), devious microbial Saturday-morning-cartoon sprites cavorting overhead. Pandora and the Pandemic, an allegory: the world hexed by evil forces from who knows where, obsessions with cleanliness in overdrive. But I wanted to know what Jim thought so I asked him. His email mentioned “Trump’s spiritual guru Rev. Norman Vincent Peale,” the invention of the housewife during the Industrial Revolution “as part of the continuing enfolding of ourselves with our machines,” and an excursus of the Greek myth Jim came across that claims that “hope was the worst evil unleashed by Pandora’s box.” It’s fun to think of all Jim’s works as a kind of Pandora’s box: a riot of wicked and amazing things running amok in the world.

QUICKSAND • One of Shaw’s greatest sculptures, Quicksand (2005) depicts the artist, bespectacled and unexpectedly dressed in a loud leopard-print jacket, melting into a gallery floor while tailed by a putrid zombie doppelgänger. It’s Gothic double trouble dressed up in glam attire. Duane Hanson meets Night of the Living Dead! Into what mire is this poor desperate version of Jim sinking exactly? His own nightmares? Revulsion at the demonic incubus who drives him to make so much work? A vortex of arcane information?

As with My Mirage, a ghoulish preoccupation with how the self can get all deranged and mutated swirls around in Quicksand. Who are you, really, when the self can be split into all these different forms, let alone mutate over a lifetime? And whose imagination isn’t full of ghastly horrors and fantasies and unspeakable slime? Is it a Jungian “shadow self” kind of thing? Tread carefully, kids.

RABBIT HOLES • I once had a three-hour conversation, interrupted by dog walks, over the phone with Jim at the behest of a fancy European art mag. Topics covered included Wes Anderson, hamburgers, Playboy magazine, and Michael Jackson’s crotch turning into a gun. Shaw did some FX work for Jackson’s movie Moonwalker (1988), which involved executing this metamorphosis, but the results were so unsettling that Jackson’s team removed them from the film. Like Alice, I found myself falling deep down into a strange and complex world but at a reassuring speed. It was hypnotic. The work is the same: a whole galaxy of rabbit holes, bewildering and bizarre, which somehow lead to multiple weirdly coherent worlds.

Half of our chat did not record; the computer’s memory failed, an ironic meta-commentary on the fantastic and mind-boggling density of Shaw’s imagination, matrix of references, and—not to forget—his incredible memory, too.

STUFF • In a 2017 interview for Artsy, rewinding back to the day he and Kelley quit Detroit, Shaw remembered, “We just left shit in our Ann Arbor house when we moved. . . . All these oil paintings and ceramics. . . . Literally the backyard was knee-deep in stuff.” Shaw’s work is obviously full of stuff: mythological stuff, pop stuff, movie stuff, drug stuff, sex stuff, historical stuff, musical stuff, deeply personal stuff. It is stuffed, and if not stuffed to the edge of explosion, swarming like Bosch meeting the cover of Sgt. Pepper. Often it is exploding—Pandora’s Box!—as if it can no longer be contained, like the gore inside a brain in David Cronenberg’s Scanners (1981). But it means a lot of stuff too. The tale of Shaw and Kelley abandoning the Destroy All Monsters house like battle-hungry knights in a heavy-metal power ballad captures one spooky aspect of it: Shaw’s work deals with how haunted we are by all this stuff.

TV • Another amazing Shaw sculpture is a huge engorged eyeball shooting out of a 1950s TV set straight at you, bloody veins and all. The rug underneath is a puddle of oozy toxic waste. Ah, Dream Object (Eyeball TV Model) (2006). Horror cinema is full of TVs riddled with ghosts or bewitched into hideously organic life. Remember the wraithlike hand beckoning the little girl into the television in Poltergeist (1982)? Change the channel: What about the slow-crawling but unstoppable demon from The Ring (1998)?

Since Shaw is a real horror maven, those movies must have shaped his creepy dream, but isn’t the sculpture also the perfect emblem of paranoid fantasy in his work? The TV that watches you. Fast-forward to right now and we’ve all ingested stories about Amazon’s Alexa and various other electronic assistants eavesdropping on their owners in order to snatch valuable commercial data about their viewing habits and favorite products. Yup, just because you’re paranoid doesn’t mean they’re not after you.

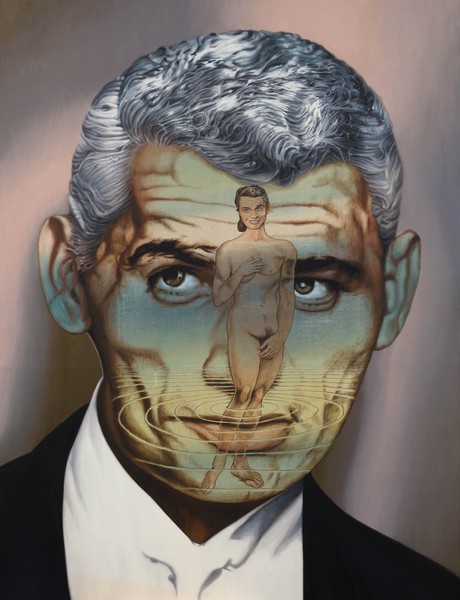

UNTITLED (OBLITERATED HIGH SCHOOL SELF-PORTRAIT, 2004) • OK, we’re returning to the trippy high school portraiture seen in My Mirage, but the sitter for this particular portrait has gone beyond a state of drug-induced face melt: their face is a void, a black hole with a murk of tangled Ab Ex brainwaves inside it, all framed by a mushroom-cloud Afro. Before I had the A-to-Z idea, I was going to call this whole piece “Studies for a Portrait for Jim Shaw” with this work at the center, talking about how Shaw’s work is powered by a craving for obliteration via drugs or religion, especially. And I was gonna explain how the cosmic void at the heart of the picture relates to Shaw’s work because there’s no fixed or definitive style there: it’s got the wicked ever-mutating potential to be anything—cartoon, opera, sculpture, portrait—in the same way that Shaw himself has been a member of Destroy All Monsters, a frazzledrip fiend, a dad, an SFX artist, a musician, a collector, a folklorist, and, yeah, an artist. Fuck Walt Whitman, this is what containing multitudes looks like, and it can be kind of terrifying. No coherent portrait is possible. Anyway, I was gonna do all that and then the psychological implications were really huge so I didn’t, and anyway I think it’s all captured in the snapshot.

WORLD, THE HIDDEN • Another collection that metastasized out of Shaw’s inveterate haunting of thrift stores, The Hidden World focuses exclusively on strange, pathetic, and oddball Christian materials: leaflets full of whacked-out scriptural hermeneutics, bad rock records, gnostic charts. But all of Shaw’s work might be a freaky investigation of multiple hidden worlds at once: the underworld of the psyche illuminated by psychedelic drugs, underground pop culture, creepy religious sects, the shadowy cabals of conspiracy theories. This may all relate, biographically, to the mind-warping effects on Shaw of growing up in a Michigan town that was the headquarters for Dow Chemical in the 1950s and ’60s. Among the military-industrial conglomerate’s staff onsite was legendary chemist Alexander Shulgin, the wizardly man responsible for the synthesis of many psychoactive compounds. What else were they up to? Was there something in the water?

ECSTASY • Shaw once took MDMA (a.k.a. Ecstasy, “X,” “disco biscuits”) at a national park in California in the 1980s and had a really wonderful time. This is also a man who was once passed a joint by Timothy Leary. Shaw’s work is full of intoxication—if you haven’t noticed by now, what drug are you on?—and it’s an intoxicant, too, just like Blake or Bosch or David Lynch, frying with trippy magnificence.

YOU • Apocryphal Native American proverb coined by Shaw for the show-within-a-show of thrift store paintings at The Rinse Cycle in 2013: “You think you own your stuff but your stuff owns you.”

ZERO • “My life’s philosophy,” Shaw once said in an interview, “is summed up in the Incredible String Band line: ‘I know nothing and know that I know nothing.’”

I’m not invoking that to create a nihilistic climax. Yeah, it’s another loop, just like St. George and the Dragon, but it’s also a means of transcendence. All the knowledge and information collected in this guide are ultimately futile because an infinite amount of mystery and/or still more unknown or unnamed information about the self, history, and the world lie beyond it. That’s before we deal with how the imagination hexes and mutates all that into an infinity of other strange and insane stuff. But that’s OK because it is, somehow, what Jim Shaw’s work is about.

Jim Shaw: It’s After the End of the World, Don’t You Know That Yet, Gagosian, Davies Street, London, April 11–May 18, 2024

Artworks throughout © Jim Shaw