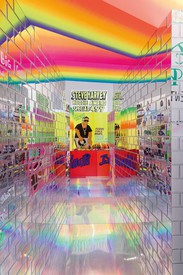

Lauren Halsey is rethinking the possibilities for art, architecture, and community engagement and produces both standalone artworks and site-specific projects. Combining found, fabricated, and handmade objects, Halsey’s work maintains a sense of civic urgency and free-flowing imagination, reflecting the lives of the people and places around her and addressing the crucial issues confronting people of color, queer populations, and the working class. Photo: Czariah Smith

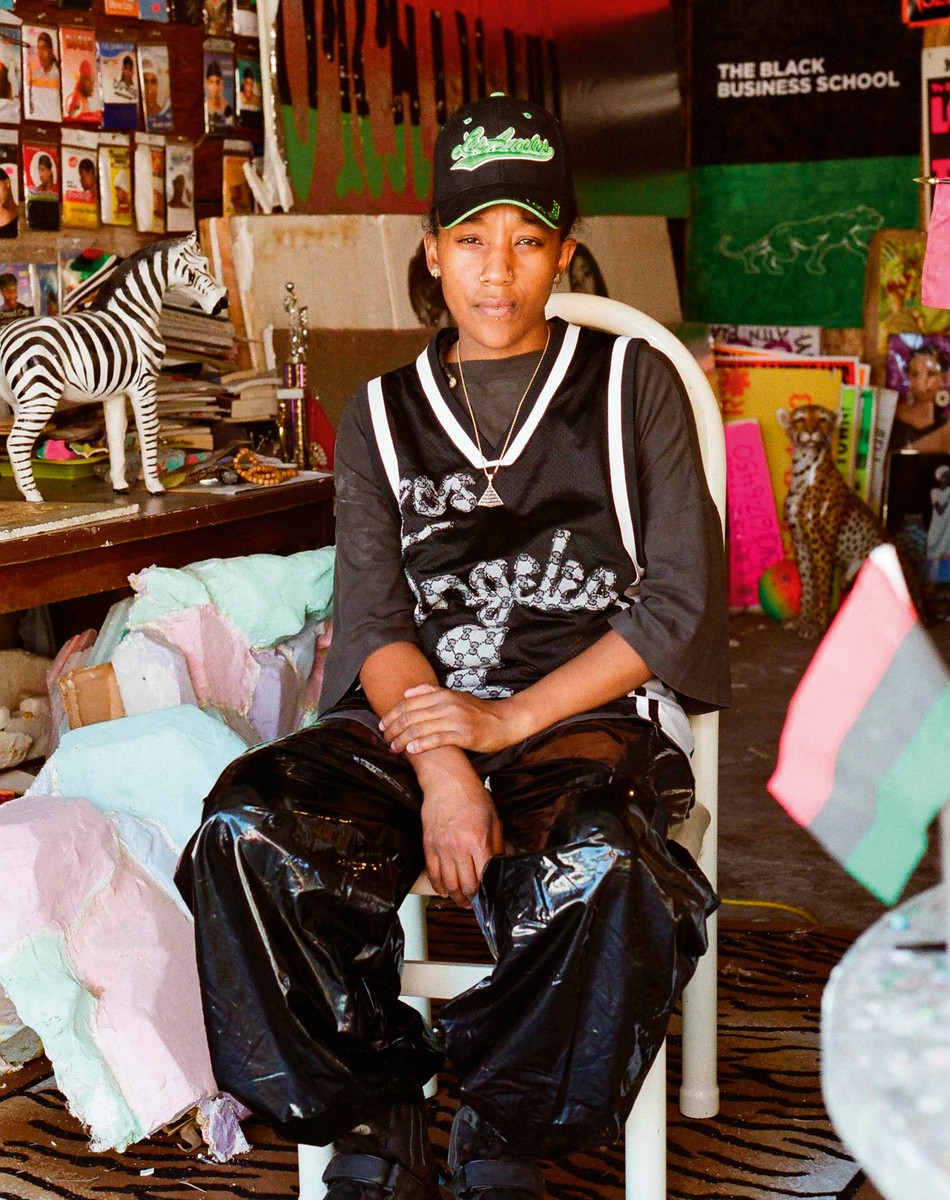

Essence Harden is the cocurator of Made in LA, 2025, curator of Frieze LA, Focus 2024, and a visual arts curator at the California African American Museum. Photo: Julia Johnson

Utopia is not prescriptive; it renders potential blueprints of a world not quite here, a horizon of possibility, not a fixed schema. It is productive to think about utopia as flux, a temporal disorganization, as a moment when the here and the now is transcended by a then and a there that could be and indeed should be.

—José Esteban Muñoz, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity, 2009

Lauren Halsey is the funkified architect of South Central. An engineer of space and archivist of labor, Halsey is a conduit of Black geography. She assesses the geographical as both a marker of place and a maker of time, interrupting impositions (singularity, linearity, and the physical) to make way for a confluence of substances. She is a funkstress, after all, a mover and creator of liberated aesthetics, sounds, and hues, forging landscapes that teeter near (or have we already had?) liftoff.

Halsey’s drive to sustain/remember and build/flourish requires a bending of time, which holds looking back/forward as a singular enterprise. Here, José Esteban Muñoz’s investment in utopia as a type of study—a means to re/create, re/form, re/figure, time and place as a liberatory strategy—finds a home in Halsey’s sculptures and installations. South Central becomes the site of transcendence, neither fantasy nor escape; the utopic here is a memory and promise of what was/is/will be.

On the occasion of her first solo exhibition with Gagosian, in Paris, Halsey and I chatted about materials, the archive, family, and Los Angeles, her generational home.

—Essence Harden

Essence HardenWhat was the impetus for this body of work? You mentioned it being particularly personal, so when presented with the space and the date, what conceptually was on your mind?

Lauren HalseyOn a sort of spiritual level, I wanted to spend time creating artworks that would fulfill me, especially energetically. As an exercise, building the foil-work compositions brings me joy and a bit of a high, at times, because I’m composing with my favorite ephemera and material culture, sourced hyperlocally as well as from my personal archives. As the work builds, everything gets conflated with Funk aesthetics and there are moments when composing or imagining that I reach my level, a sort of Funk nirvana. Over time, as the foil works started to develop, I realized thematically they would be about eras in the neighborhood that had profound effects on me, ranging from the mundane to celebration to death, on both a community and a familial level. As for the engravings, they’re scenes of quotidian Black and brown life in a nonlinear context. Their chronology ranges from the 1920s to now. Some of it’s political, some of it not . . . just us being.

EHCan you walk us through some of the pieces?

LHThere are eight protruded engravings and eight foil works in the show. The foil works are maximal, technicolor assemblages that are imbued with reality but conflated with aspirational fantasies of my neighborhood. Some of the works function as eulogies, others as party, others as documentation of a space and its poetics.

slo but we sho: everybody is going to make it this time [2024] depicts a scene in my grandmother’s home with my aunt Fawn, while also referencing the block quite literally: Freddie’s roosters, my inherited play, grandmother Alberta’s living room, the quintessential footprints poem, vernacular signage: waz up!, where its at?, et cetera.

an ode to margaret prescod and the black coalition fighting back serial murders [2024] refers to the “Grim Sleeper,” who hunted and murdered Black women in South Central Los Angeles from the mid-1980s until he was caught, in 2010. I lived on the same street as him and attended middle and high school with one of the victims. This artwork is a nod to not only that era but many, to this very day/moment, wherein Black women are moving through very volatile and evil contexts without support on a systemic level. Somehow we manage to still make it over the hump. an ode to margaret prescod and the black coalition fighting back serial murders [2024] includes women who were his victims and also women I view as our pillars, defending and providing for Black women in their work every single day: Margaret Prescod, the Sisters of Watts, et cetera.

we want a full and complete freedom (high voltage Funk) [2024] is a nonlinear sort of experimental still life of my walks and bus rides up and down main avenues and boulevards in South Central and on the Eastside of South Central. Because I rode the same buses for over a decade I was able to document elaborately how small businesses transformed themselves over time aesthetically. Some included are Deryl with the Curl Hand Carwash, Gwen’s Ice Cream, Charlie’s Strip Club, MasterBurger, and a host of mini markets. It also includes Okeneus the Love God from Team Knowledge God, a group of South Central LA superheroes, who would wheat-paste these really amazing ’n’ dense staged photos of himself doing things in a postapocalyptic South Central: eating strawberries, flying, dancing, et cetera. I was obsessed with him for a very long time.

I’m adding to my archive of material every day, whether I’m composing with materials or not. I’m always buying things that I know must be preserved, especially the handmade.

Lauren Halsey

EHI want to think about this term “assemblage” and the way these works hold memory, sensation, feeling, and eulogy. I’m quite obsessed with assemblage as strategy and think LA’s relationship to the term, post–Watts rebellion, was in extending it toward a socioracial geography in the “cast away” material. And so much of your work carries that legacy—the way you think through these various sites, of the archive and of archiving, use value, and the state of the object.

How has the impact and your relationship to assemblage developed? How do you see yourself fitting into that legacy?

LHI’ve always used collage as a medium and knew that eventually I wanted to transcend the image, or the representation of an image, by composing with the actual object, e.g., instead of carving a pack of Coco Egypt incense or digitally collaging a photo of the Coco Egypt pack, the foil works and assemblage process allow for working with ephemera and neighborhood/familial/personal archives in a more dimensional context. I can use the actual Coco Egypt pack itself. I know a lot of folks worked with materials that came out of the uprisings, but my materials aren’t inherited from streetscapes (only the flyers/signs I collect). My gathering process is very different and sort of costly, but I see it as recycling money back to my inspirations and a collective community energy. I buy a lot from small businesses and vendors in the neighborhood until I have enough to build a bit of a vocabulary to begin a particular work. For example, I have an idea for a foil work that can’t start until I buy all sixty stuffed animals from a street vendor up the street.

EHAnd so assemblage here works as an imbuing and spirit? One that’s sustained not from the physical remnants, necessarily, but in the substance of what remains?

LHYou hit the nail on the head! Yes, exactly this. I’m adding to my archive of material every day, whether I’m composing with materials or not. I’m always buying things that I know must be preserved, especially the handmade. I hope to donate my archive to the Southern California Library on Vermont Avenue one day.

EHCan you speak to the function of architecture for you as something that is, on the one hand, the built environment, and on the other, a conceptual space from which to create?

LHI had a quick chat with the artist and architect Amanda Williams yesterday morning. She was a California College of the Arts professor while I was there in 2007–08. Unfortunately she wasn’t my professor, but I worked out of the studio parallel to the one where she taught. I wanted to be her, at the time, this fierce Black woman architect. I didn’t finish, and my Black male professor encouraged me not to; he said architecture wasn’t for me. I’m over it now but at the time it broke me.

Anyway, we were on a really quick Zoom yesterday morning, and she spoke about architecture as being our medium and many other things, and I agree. The discipline couldn’t hold me when I was in school. I don’t even consider the discipline or burden myself with it. I quickly knew that my interest in building tangible and ambitious Black space had to be articulated across sooooo many different modalities if I was going to figure it out without the discipline on my side. In 2014, I knew the gypsum carvings were symbolic of walls and literally would one day become walls to compose space with (once I had the support and money to do it). I see the protrusion engravings in this show the same way. Yes, they’re artworks on a nice wood panel hanging from cleats, but actually the conceit of me doing them is for the exercise of figuring out protrusion engravings on a technical level because they will become the actual cladding for twenty-foot walls in the architecture I’m presenting next year.

EHI’m interested in hearing more about the relationship between the foil and the engraving works. How do you understand them compositionally together?

LHI see the two typologies functioning a bit differently. The foil works are not only tactile but they also describe our palette and, specifically, South Central LA painting sensibilities: our pastel businesses, Day-Glo signage, dreamy gradients. Miniature cardboard businesses also protrude from some of the works; some are personal landmarks and some are ideological community spaces that existed before my time.

As for the engravings, they’re literally wall works whose content describes our records. They’re less fantastical and aspirational at times. They represent symbols, flyers, people, businesses, et cetera, in the archive I intend to build walls with. I thought it would possibly be nice to juxtapose a room of the tangible and technicolor with monochrome representations of these places. But the main thing is, I’m thinking about them as wall works quite literally and wanted to introduce the Western Ave project in this context by exhibiting the cladding (wall works) as artworks.

EHYou’ve always known the overall vision for your work, and now you’re in this moment where there’s a different relationship to scale and possibility. Can you talk more specifically about what that vision is?

LHTotal freedom to be and design/build/make at a scale without intense institutional compromise, internationally and at home.

Lauren Halsey, Gagosian, rue de Ponthieu, Paris, March 21–May 25, 2024

Artwork © Lauren Halsey