Brice Marden was an artist of extraordinary gifts. He had a profound understanding of the world as something to be observed, of the subjectivity of perception, of visual pleasure, of the jolt of excitement from seeing things as they are. He looked to solve problems and collected his solutions on paper and canvas, linen and marble, but insisted we have our own experience with what we see in his work. He was a painter of rare insight into the pleasure and poetry of his medium, always dedicated to gesture, chance, substance—the elemental matters of art.

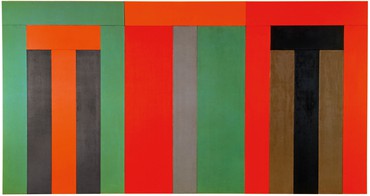

Brice was fond of hats; it was one of his trademarks. In the last couple of decades he was nearly always clad in a simple black watch cap. Brice was always a traveler but never a tourist. When a place interested him it became ingrained in his art, and he would return many times over the years. He had studios in Hydra, Marrakesh, Nevis, Tivoli, and of course Manhattan. He reveled in the details of each environment and let those places inform his work—from the ancient to the avant-garde. Brice was somehow both things. He created wholly unforeseen paintings that were new and now and timeless all at the same time. He often constructed his paintings of multiple panels to explore the problems inherent in two colors colliding. If edges are the places where two things meet, Brice positioned himself to work in the gap between two edges.

Brice moved to Manhattan in the mid-’60s, when New York was the center of everything exciting that was happening in art. Brice was in the middle of it all: he became a friend and acolyte of Jasper Johns, studio assistant to Robert Rauschenberg, a denizen of Max’s Kansas City. He was of a particular generation of artists who stood out for their fierce individuality. They were friends, but never a school or movement or ism, all voyagers following their own startingly original paths. Brice’s early success at the Bykert Gallery in 1966 set a ball rolling that only gained momentum. Career retrospectives came at the Guggenheim in 1975 and the Museum of Modern Art in 2006. In between and since, his achievements were celebrated and recognized the world over.

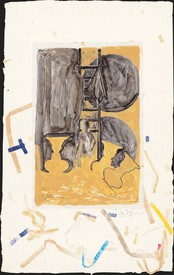

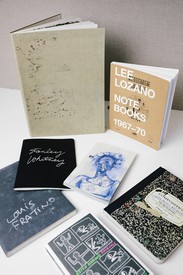

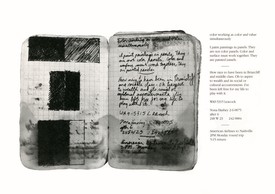

Brice and Helen were friends of mine for many years and I had my first chance to include a work of his in a group show in Los Angeles in 1985, Sixties Color. In 1991, I was able to bring together the five canvases, eight drawings, and related notebooks that constitute Brice’s Grove Group (1972–76) for a solo exhibition at our flagship gallery on Madison Avenue. It was not only the first solo show of Brice’s work that I hosted but the first time the series had been exhibited as a group since their making. It was also the first time Brice had seen them together. After his first experience in Hydra, in 1971, Brice returned to Manhattan with his impressions of the Grecian landscape and notebooks in hand. Over the next several years he created paintings that probed the memories of the colors he discerned from Hydra’s remarkable landscape: the subtle difference between the blue side and the gray side of an olive tree’s leaves, how they shimmer silver in the wind and contrast with the colors of branches, soil, and sky. He tapped the sacred grove of the muses, worked with the information nature had given him, and developed his own signature in the dialogue between classicism and abstraction.

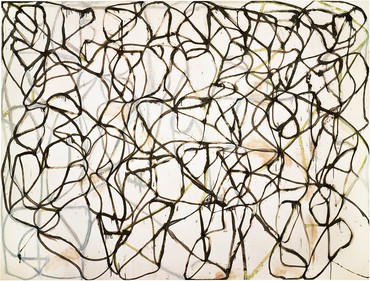

In the age of Primary Structures and “systems,” Brice was at the forefront yet apart. At the time he was producing the Grove Group, the poet John Ashbery put it this way: “Marden’s canvases are monochrome, but the resemblance to reductive art ends there. For, rather than reducing the complexities of art to zero, he is performing the infinitely more valuable and interesting operation of showing the complexities hidden in what we thought to be elemental.” Brice gave the monochrome a soul, and the tension between formal thinking and romantic thinking in the work reflected the same duality in its maker. His investigations into the formal matter of art always had a human scale—panels made to the dimensions of a body, gestures that explored the edges of an arm’s reach. And for an artist who, as a student at Yale, insisted that he never quite understood the tricks and strategies of Josef Albers’s famous color curriculum and gravitated away from Hans Hofmann’s “push and pull,” Brice became a colorist in the caliber of Henri Matisse and Mark Rothko. Maybe even surpassed them. He paid attention not only to the emotion of color but to the physical substance of its appearance; that color has a presence in the mind just as it has a presence in the room. This sensibility and concern remained constant as Brice’s work evolved beyond his deceptively straightforward monochromes to embrace the gestural fugues and variations of the second half of his career. If the monochromes are arias, the poetry and vitality of his calligraphic compositions are the dance. You feel Brice’s colors in your bones.

This is what Brice shows us in the gifts he left behind: that color has an uncanny presence, that memory has a palette, that poetry can move an artist’s hand just as it moves his heart. Brice will be profoundly missed.

Artwork © 2023 Estate of Brice Marden/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Brice Marden: Let the painting make you, Gagosian, 980 Madison Avenue, New York, November 2–December 22, 2023