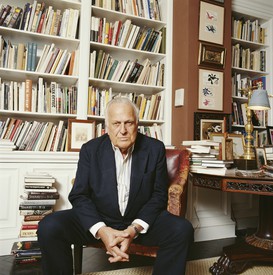

Annie Cohen-Solal is a distinguished professor in the Department of Social and Political Sciences, Bocconi University, Milan. She won her doctorate at the Sorbonne and has taught in universities in Berlin, Jerusalem, New York, Paris, and Caen. Her biography Jean-Paul Sartre: A Life (1985) has been translated into fifteen languages, and her other books include Painting American: The Rise of American Artists, Paris 1867–New York 1948 (2000), Leo & His Circle: The Life of Leo Castelli (2010), Mark Rothko: Toward the Light in the Chapel (2014), and others. Photo: Sijmen Hendriks

I have been interested in the issue of immigration ever since I entered the art world. I began my career as an intellectual historian: I was a scholar of Jean-Paul Sartre and wrote his first biography. It was quite unexpected that I would fall into the orbit of the art world, let alone so fast, but two days after I arrived in New York City, in 1989—I had just been nominated cultural counselor to the French Embassy in the United States—I met Leo Castelli at a dinner. Out of the blue, Leo told me, “You don’t look like your predecessors.” (I was the first woman in the position.) “You’ll take New York city by storm and I’ll teach you American art. Come to the gallery tomorrow, I have a show with Roy [Lichtenstein]. Come for the opening and stay for the dinner.”

From that moment on, I followed in the footsteps of Leo Castelli. It so happened that there were any number of resonances between his trajectory and mine: he was born into a Jewish family in Trieste, I was born into a Jewish family in Algiers, and both of our family histories included traumas of displacements and pogroms. We shared multiple cultural roots and could navigate between languages, playing with words, weaving through German, Spanish, Italian, French, and English. We belonged to the same tribe.

For my first Christmas in New York, Leo asked me to join him in the Caribbean on the island of Saint Martin. Arriving at the airport there, I was greeted by Jasper Johns, who was immensely warm. And that was typical: increasingly welcomed in this sophisticated world of artists, critics, and gallerists, I walked a fabulous red carpet into the flourishing American art world and was thrilled to be included in it. I could see how Leo, with his cosmopolitan training in Europe and his fascination with the Medici, had been able to import those cultural elements into the United States. When he arrived in New York in 1941, fleeing a Europe on the precipice of war, the local cultural life was to him “like a desert.” But because of the catastrophic political tensions that had steadily succeeded each other in Europe—World War I, waves of fascism, civil wars, World War II—America became a new creative center. Marcel Duchamp, Hans Hofmann, and so many more were uprooted and began anew there. With the extraordinary speed that is characteristic of the United States, and with its financial means and the freedom of a thriving civil society, a new culture emerged. Thanks to charismatic personalities such as Castelli and Alfred H. Barr, Jr., endogenous and exogenous factors combined, and by the time I arrived in New York, the city was offering its artists an incredibly fertile ground.

In my job as French cultural ambassador, I operated like an anthropologist, in awe of everything I was experiencing. I loved the interdisciplinarity and the fact that it multiplied my creativity. In France, institutions were difficult to access, contemporary art was little celebrated (to say the least), and disciplines were compartmentalized. To a certain extent, this compartmentalization persists to this day, and this is exactly the story behind my exhibition and book Picasso l’étranger in 2021–22, the first incarnation of a project that is now being carried over to New York with A Foreigner Called Picasso at Gagosian.

In 2015, I attended the opening of the new Musée national de l’histoire de l’immigration in Paris. There I spoke with the historian Benjamin Stora, the museum’s scientific advisor, and he expressed his interest in doing a show about Pablo Picasso, who was denied French naturalization in 1940. Laurent Le Bon, who had just become president of the Musée national Picasso–Paris, attended the same event, and I asked him if he had spoken with Stora. He hadn’t, and it was once again clear to me that compartmentalization—the separation of the art world from the worlds of sociology, anthropology, history, science—was still a reality in France. My academic training and my personal upbringing involved multiple cultures and disciplines; I am at heart a cultural historian and a political sociologist, and there is nothing I like more than building bridges.

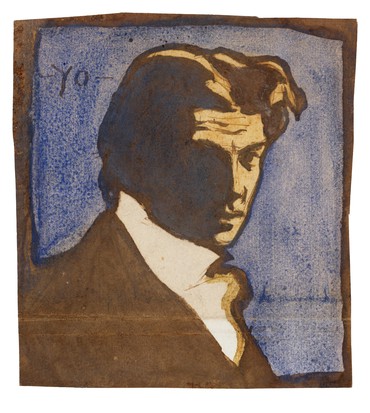

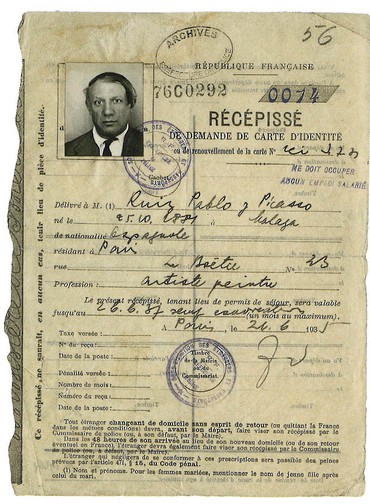

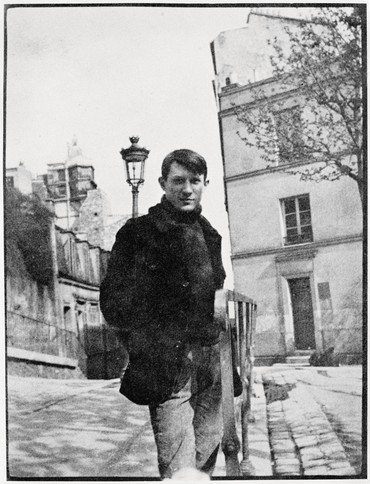

I soon invited Le Bon and Stora over for dinner, introducing them, and the project was launched. The first stop was the archives, both of the Paris police department and of the Musée Picasso. Beginning with three large boxes of Picasso’s correspondence, I focused initially on his letters among his family around the time of his arrival in France in 1900. It was essential to put my feet in Picasso’s shoes: what did he feel as a foreigner in a country that was then hypernationalistic? A country whose president, in his speech to open the Exposition Universelle of 1900, essentially said that the people who had come there from all over the world had come to admire the genius of France? Picasso must have heard this arrogance with some incredulity: he knew there was genius in him. At the age of fourteen, he had reproduced Velázquez’s portrait of Philip IV in the Prado, and he knew that his copy was better than the original. I too certainly registered the arrogance: it reminded me of what I myself had faced when I arrived in France at the age of fourteen. I am interested in the way societies look at the other, the pariah, the foreigner, the one who does not belong, because it’s also my story. In my research for the show, I tried to find the weak signals, the microelements, that build up one’s system of reactions and interactions.

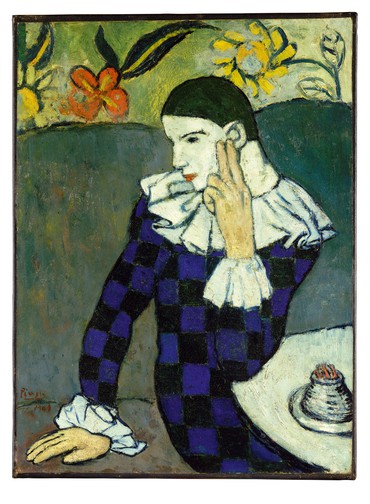

As my work progressed along this line of inquiry, Picasso’s precarity emerged continually. Throughout his time in France, he continuously felt vulnerable, knowing that he could be expelled at any time. This was his Achilles’ heel—but he hid this fear, and went about constructing networks of powerful friends, collectors, and collaborators that protected him in various ways. He was extraordinary about creating networks. The collector and lawyer André Level, for example, protected Picasso throughout his life, advising him on navigating French law, French finances, and so on. The same is true of Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, the German dealer who worshipped Picasso’s work. Kahnweiler created the first global awareness of Cubism, brought in fabulous critics to engage with this new type of art, and built an immense commercial network of new clients all across Eastern Europe, helping him to place Picasso’s work in collections and museums from Düsseldorf to Berlin, Prague, Moscow, Munich—all while Picasso was barely recognized in France. To put it simply: his works were not collected by museums in the country where he lived and worked.

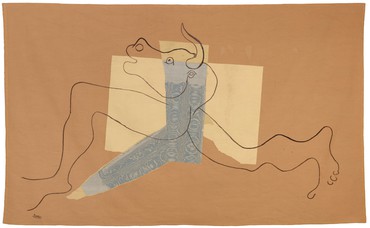

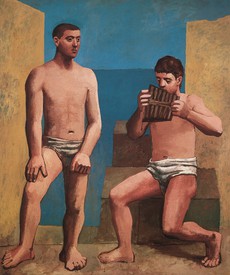

As I engaged with the existing scholarship on Picasso, it was clear to me that these geopolitical topics had been ignored—the focus was always on a particular medium, or period, or his relationships with muses and his family. I offer a different approach. The political and social status of the artist is a primary element to understand if we want to engage in art fully. To understand Picasso’s work—why he is Cubist, classical, Surrealist, political—we have to go back to his status in French society.

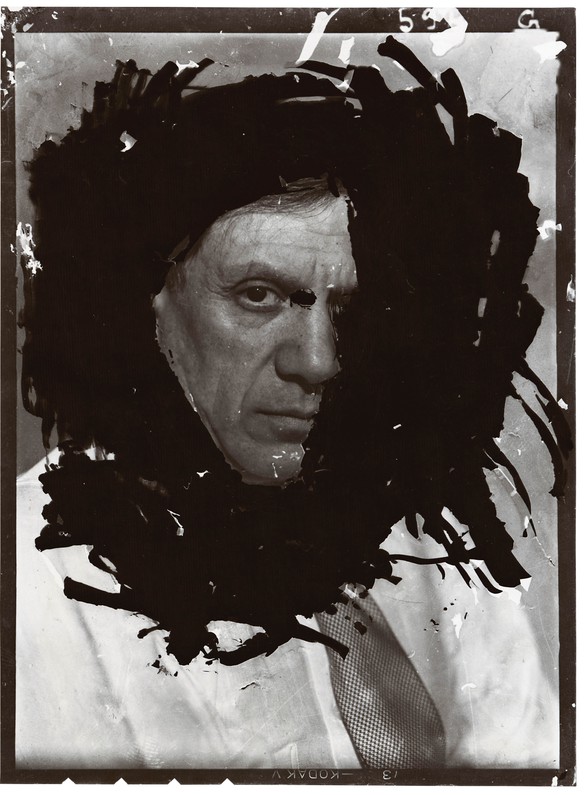

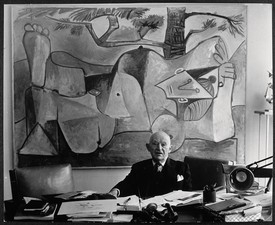

In the police archives I saw the photographs, files, and fingerprints collected on Picasso throughout his life in France. Some of these photos came as something of a shock: he looks like a mafioso. This is not the Picasso we know; what the police see in him is the foreigner, the alien, the pariah. At the time, the French police department tasked with tracking foreigners was the most sophisticated in the world. And Picasso was targeted for three reasons: initially because he was a foreigner who couldn’t speak the language; because, having lived with Catalans, he was suspected to be an anarchist, which he truly was not; and because, as an avant-garde artist, he was rejected by the Académie des Beaux-Arts. In 1940, he filed for naturalization because, with the German invasion approaching, he feared for his life, but his application was rejected. He was then invisible in France until 1944, when he decided to join the Communist Party. But after he donated ten beautiful paintings to the new Musée National d’Art Moderne, in 1947, he was granted the status of privileged citizen.

Picasso is relevant today, then, as a model of the behavior of someone treated as a dangerous alien. The exhibition and book focus on an artist who was the target of banal xenophobia but who, through his shrewd intelligence and political acumen, managed to navigate the country’s tensions and win. At the present moment, who does not see how the French eventually coopted Picasso? He is celebrated in a museum of his own, the Musée Picasso, at the center of Paris, and is considered key to the country’s history and prestige. In this framework I view Picasso’s trajectory as that of a comrade. He is a guide, a compass for us all. What he tells us through his behavior is that one is never a victim but one has to fight and win. Though people often infer that a foreigner has no agency, Picasso proves exactly the opposite.

A Foreigner Called Picasso, Gagosian, 522 West 21st Street, New York, November 10–February 10, 2024