Founder of Studio AR.CH.IT, Milan, Luca Cipelletti is an architect and interior designer who focuses on the relationship between art and architecture and on exhibition spaces, collections, and museum design. Since 2018, his design projects have been represented by the Giustini/Stagetti gallery, Rome.

Sara Fumagalli is an Italian curator, writer, and event organizer who currently serves as curator at GAMeC—Galleria d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea di Bergamo. She has collaborated with a number of film festivals in Italy and abroad such as the Annecy Festival, the Bergamo Film Meeting, and the Siena International Short Film Festival.

In Rachel Whiteread’s sculptures and drawings, everyday settings, objects, and surfaces transform into ghostly replicas that are eerily familiar. Through her use of the casting process, her subject matter—ranging from beds, tables, and boxes to water towers and entire houses—is freed from practical use, suggesting a new permanence imbued with memory. Photo: Dan Kitwood/Getty Images

In 2021, when Rachel Whiteread conceived . . . And the Animals Were Sold, her solo exhibition at the Palazzo della Ragione in Bergamo, the pandemic was entering a less distressing phase, but the measures to contain the virus were still stringent in Italy, the pain of losing loved ones was still very present, and the vulnerability of our bodies and lives was still a part of our daily existence. The period led Whiteread to connect the experience of conceiving . . . And the Animals Were Sold with House (1993), her casting of an entire Victorian house in East London, a project for which she won the Turner Prize. House preserved traces of the people who had lived there, their history, and their memories, although the preparatory operations for the cast—bricking up windows, mending cracks, removing wallpaper, and so on—produced a result that ended up undermining the sense of protection and security associated with a home. That same year, during a residency at the DAAD Foundation in Berlin, the artist created Untitled (Room), a cast resembling the room of a house but actually made from an armature constructed for the occasion. So this room was devoid of history and emotion, lacking even functional elements such as switches, entrance and exit doors, and signs of a heating system, extending House’s denial of any sense of security and familiarity. . . . And the Animals Were Sold moves within a space that encompasses House and Untitled (Room) to the extent that it evokes feelings of both familiarity and strangeness, desire for closeness and fear of closeness, protection and confinement, sharing and isolation. During the pandemic, in fact, our homes became our havens but also our claustrophobic prisons. They constituted an extension of our body, which suddenly and constantly became the center of our concern: a body to protect, a body to distance, a body to quarantine, a sick body, a vaccinated body, a threatened body.

As often with Whiteread, connection with her personal experience was crucial to the realization of the work. In Bergamo she presented sixty seats, each duplicating the empty space between the legs of one of two chairs and each combining three different types of marble and Sarnico stone, materials used historically in local construction. These forms interested the artist as hidden spaces offering a sense of privacy and security within a domestic and familiar environment at a moment of great vulnerability. Not only that: with . . . And the Animals Were Sold, Whiteread aimed to reflect on the disruptive experience of the pandemic and to offer the city of Bergamo a tool for initiating a process of healing.

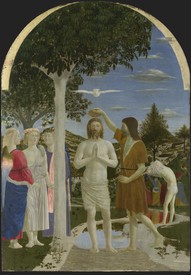

Upon entering the Sala delle Capriate, one got the feeling of crossing the threshold of a sacred place inhabited by lost souls—as the artist herself referred to her sculptures in a recent interview—but resonating with a sense of life.1 The rigorous geometry of the sculptural forms and their restrained and orderly arrangement in space inhibited easy emotional appeals, making room for a reflective and profound emotion experienced in tranquillity. Whiteread has said that on this occasion and others she drew inspiration from Piero della Francesca’s Flagellazione di Cristo (Flagellation of Christ, c. 1468–70), where the master employs proportions and composition to organize his figures as sculptural forms in spatial volume. Whiteread worked similarly and skillfully to arrange the seats within the immense spatial volume of the hall.

Comparisons between Whiteread and Piero in the treatment of volume, space, and mass have been discussed often and many connections have been found between the artists, particularly in their interest in composition, form, and proportion. But a dominant aspect emerges in . . . And the Animals Were Sold: the absence of rhetorical amplification in the figures and construction of the Tuscan master’s painting echoes in Whiteread’s installation, with its solemn calm, its sensitive, dignified sobriety. Piero’s figures are mute, inexpressive; they are presences that communicate solely through the fact that they exist in this specific form and substance.2 Likewise, Whiteread’s sixty seats speak to the spectator through their sculptural presence, their material and formal qualities, the relationships established between them and the surrounding architecture, the color variations merging into the hues of the hall’s walls, the harmony of the whole—and not because they represent something. Rather, they stand for something else, expressing absence while highlighting a connection with the body: what is the purpose of a chair if not to accommodate a person?

Whiteread’s installation was significant not only because it offered an opportunity to process the trauma of COVID-19 but also because it served as a discreet admonition, or exhortation, to become aware of our current relationship with the pandemic. Today we are in a moment when, after a period of pain and worry, we are driven by the desire to look beyond, to forget, to focus on the lightness of the present moment. Whiteread’s installation assumed historical relevance by compeling us to consider the shared attitude that makes us impatient with discussions of the pandemic. It constitutes a statement about the importance of stopping to think, to make space, to question what we have experienced, because only by actively processing the trauma will it be possible to move forward with awareness.

—Sara Fumagalli

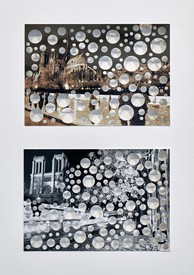

Luca CipellettiOn the evening of March 17, 2020, more than seventy military trucks were seen moving piles of coffins from Bergamo to other parts of Italy, since the local crematoria were already overloaded. These shocking images alerted the entire planet to the fact that COVID was not confined to China but was in fact the most devastating global pandemic of the last hundred years. The world was unprepared to fight such a difficult battle, and Bergamo became a symbol, the epicenter of the pandemic in the Western world.

In 2021, you were invited to create an exhibition in Bergamo. For decades now you’ve been working with the concept of memory—the memory of buildings, their architectural elements and furniture: staircases, doors, windows, chairs, mattresses—the memory of souls. When you received this invitation, what were your preliminary thoughts before traveling to Bergamo?

Rachel WhitereadWhen I was asked to make this exhibition, there wasn’t a preconceived idea—I wasn’t invited to make a memorial for those who died during the COVID pandemic, for example. If I’d been asked to do that, I probably wouldn’t have accepted, to be honest. These things are so emotive and complex. And for me, when I make a memorial, I have to feel it’s the right moment in time. The pandemic was still so fresh and so complex in everybody’s minds at that point; no one had really figured out how to deal with it, and no one really knew the sort of emotional and physical damage it had done to the world.

So when I went to Bergamo, I went with a very open mind. I didn’t know what I wanted to do, I just wanted to go and have a look. I journeyed there with my colleague and we were shocked, actually, by how people reacted. The city had been so wounded by what had happened that they hadn’t in any way come to terms with it. In the hotels, in the restaurants, in the shops, walking down the street, we were treated with a lot of suspicion. It was really odd, and I was very surprised because I know Italy extremely well and I’d never felt like a sort of alien there.

So when we went to see the space at the Palazzo della Ragione for the first time, within fifteen minutes of walking into the place I knew what I could make happen there. I knew that I could do something that might aid in the healing of such a catastrophic scar.

LCWhen you went to Bergamo, you met Lorenzo Giusti and Sara Fumagalli, the director and curator of the Galleria d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea di Bergamo, as well as the local authorities. Just as important, you had the chance to meet the citizens of Bergamo and to grasp the aftermath of the battle. What was your feeling after visiting the site, and how did your preliminary idea develop?

RWThe original idea was to keep the space open. In a lot of Italian cities in the summer, as you know, there are public spaces that are used almost like salons, there are poetry readings and musical performances and all sorts of things happening there. When I left Bergamo and returned to my studio in the UK, I was thinking about that, and about how people could and would move around the space.

Initially I wanted to use as many chair pieces as I could. The chair pieces are motifs that I’ve used for a very long time. They stand for an architecture of the people, in a way—I wouldn’t say they’re stand-ins for humans, but they have to do with how we’ve developed in the world. They seem to be a very good way of trying to bring a form to the very abstract notions of disease and catastrophe.

LCYou made sixty stone pieces, each the shape of the space beneath a chair. You’re primarily known for casting but in this case the pieces were carved or cut from the stone, using two different forms. How new is this for you?

RWI normally cast things, but I’ve made hand-carved works before as well. I knew that in Italy, master craftsmen have been dealing with stone for centuries. It has to do with the way in which Italy was built, the way in which the architecture of the surrounding area and the cathedral and the square were built. Obviously when these things were constructed five hundred years ago, they were built by hand, and now we use machinery. But there are experts who really know how to make the stone sing and play.

Right from the beginning, I felt it could be very much a sort of concerted effort by the entire community to join in and make this together. People really got on board and wanted to be a part of this healing situation for the whole community. I was very touched by that, actually; I felt that it had hit a nerve, and that it was powerful and the right thing to do for the situation.

LCAs an architect, I have projects in the Bergamo area and I’m familiar with the local stones you used, all with beautiful names. They’re very Italian words and sound like the names of the people portrayed in the medieval paintings in the ancient palazzo housing your exhibition. More important, these local marbles, which were used in the actual building of the palazzo, are sort of multipliers for the two different forms you used for your sculptures. Each form was made using all four marbles, but sometimes with different finishes—smooth, sandblasted, et cetera—giving you the opportunity to generate an incredible number of pieces that are both very similar and slightly different. This seems connected, in a way, to the idea of humanity in its similarities and its diversity.

RWI’d say that my objects and sculptures have a way of representing humanity—from the mattresses to the chair spaces to the bars, they’re all objects that we’ve made for our bodies to use. From very early on, I’ve tried to develop that idea. The different materials that I’ve used over time as well—I always push the materials. I wouldn’t say that I’m trying to reflect the diversity of humanity with the materials, I think it’s more that the materials are reflecting the diversity of materials [laughs].

LCYou clearly have a deep feel for materials and textures, yet you don’t seem to allow yourself to be seduced by overattention to look, surface, shine, color, or extravagant materials. The various stones used in Bergamo, and the slight variations in their surface finishes, are things one notices in the quiet of looking. Their beauty reveals itself slowly, would you agree?

RWYes [laughs]. You know, to me a lump of plaster is one of the most beautiful surfaces in the world. Other people might think it looks like a bit of white chalk. I think it’s very much how the individual interprets the world, and I don’t like to overcomplicate a surface. I like to try to use a material for its materiality. I occasionally color things and I occasionally patinate things, but that’s to bring out other elements. For me the beauty of something lies in its imperfection and in its ability to be what it is—to be honest. It’s about an honesty and a depth. I suppose it’s how I kind of live my life.

LCThe way you arranged the pieces in the enormous hall of the Palazzo della Ragione was incredibly powerful: they were in groups of varying sizes, some aligned in front of architectural elements or frescoes. What was the relationship of these groups to the space? Was it related in any way to the distance we were forced to keep from each other during the pandemic?

RWOriginally I thought maybe the show would be titled “Two Meters Apart,” or something like that—that was such a rigid rule that almost the whole world was following during the pandemic, so I had that very much in mind for part of the work. But I was also very influenced by looking at the piazza outside the museum, which Le Corbusier said was the most perfect piazza in the world and that no stone should be changed. It’s an incredibly beautiful thing, with a fountain in the middle that serves as a focal point. I would stand there and just watch people gather: there would be someone with a flag taking a tour group through, there’d be schoolchildren walking across in lines, there’d be a little family unit with a buggy . . . there was always a theatrical element going on. And you know, I’ve always been very intrigued by the way people look at sculpture, because it’s such an interactive thing—people are kind of curious and inquisitive and they may look under something, or lie on the floor to look at something. So I think I was trying to somehow develop those ideas and put them together.

I was also thinking about Renaissance paintings where you have groups of figures and the perspective is slightly skewed—you maybe have five people in the background standing very rigidly next to each other and then maybe one slightly forward. As an artist of my age, when you’re someone who has been working for so long, you have this incredible lexicon of ideas drawn from your experiences of looking at art and culture around the world, and all of that stuff goes in. I always try to talk to my kids about that when I’m showing them around—to never take an experience for granted when you’re looking at something because it all adds information to the next thing you look at. We’re very lucky as humans to have memory, in that we can always work with it and play with it.

People really got on board and wanted to be a part of this healing situation for the whole community. I was very touched by that.

Rachel Whiteread

LCSomething magical happened every time I walked into your exhibition. The installation inevitably created many layers of conversation: the conversation between the sculpture and the volume of the room or the paintings along the wall, the conversations between the pieces themselves when the room was empty. As soon as a visitor came in, they became another actor, allowing another layer of conversation. The structure was very theatrical, but open-ended—you left visitors completely free to experience the installation in their own way.

RWAs humans, we’re animals of great curiosity and fearfulness and joy and sadness—you know, we have all of these emotions. I’m not religious but I go into churches a lot; they’re among the most ritualistic, almost theatrical places, and you see how people behave looking at things. A lot of it is a sort of felt reaction, a lot of it is something people do because they feel they ought to, or through great belief or whatever those things are. And this piece for me was probably the most, in a way, religious work that I’ve ever made.

When I made the piece, I just sort of made it and left, because I knew that it was going to be very emotive for me. When I came back for the opening, I just sat there and watched people, and they were coming in and they were crying and they were sitting down and then they’d be chatting to someone else and then someone would be laughing. You know, it just meant so much to so many different individuals. It was very moving.

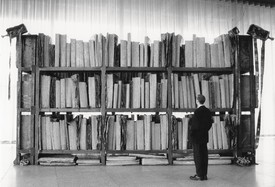

LCMemorials are often depictions of specific events or individuals. Your memorials in Vienna and Bergamo refer not to specifics but rather to a presence, or indeed an absence. They’re representations of things you recognize but that don’t physically exist: the space around books in a library, the air beneath a chair. This seems an appropriate way to bring attention to the incomprehensible number of people who died in the Holocaust or because of COVID. How do you approach an issue like this?

RWWhen I made the memorial in Vienna, I’d lived in Berlin for eighteen months, and I think if I hadn’t had that experience, I would never have tried to approach such a complex subject. When I lived in Berlin, I’d been to a number of the Holocaust sites and camps and was very affected by it. I’ve always tried to understand what makes a place, and in Germany I observed the deep shame over what had happened and the attempt to learn from it and sort of heal what had happened.

I also went to look at the site of the Normandy landings, looking at bunkers. I’d been to see Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial in America. I always do a lot of research. I’m sort of curious, but I also see that it’s part of my job. If I’m going to interpret something that was so devastating, I need to be armed with the information to try and transcribe that experience.

LCAfter millions of deaths and more than two years of lockdowns during the pandemic, it seems, weirdly, that there aren’t any lessons that have been learned and that everyone is now back to a so-called normal life. What are your thoughts about what happened? Did your life change? Did your work change?

RWI think my life changed to a certain degree, and I’m still struggling to try and hold on to that—you just think, well, certain things matter and other things don’t, and you just need to be more mindful of those things and be more present for the people that you love and want to be present for. This extraordinary thing happened, and everybody I know feels like time has sped up in a way—it’s like there are twelve gears, suddenly, and we’re all going along in twelfth gear. I’m really trying to find a way of slowing that down. It’s not healthy; we can’t work at that speed. It’s something that young people in their teens and twenties are really struggling with—they don’t really know how to fit into this new world, which is about working from home and not really interacting with people in the same way. There’s an enormous amount of mental-health problems among young people because of what happened. And older people. It did an incredible amount of damage, and I think we all need to learn from this. We have a great responsibility to the younger generations to slow down. We’re all responsible for it, as we are for climate change and everything that we’re doing to our planet. It really, really needs to change.

In terms of my work, I think it’s too early to tell, really. I normally work in periods—I’ll do certain things and then I’ll kind of move on. And I don’t feel like I’ve left that period and moved on to the next one yet. I’m trying to think about the next half of my life—no, not half but third, maybe [laughs]. The last third of my life.

I suppose one of the things the pandemic made us all think about in a way that we never had to before is our mortality. COVID certainly hasn’t disappeared. I hope people have learned some lessons and we react differently in the future. But, you know, as humans, we’re very stubborn. Incredibly intelligent, but also incredibly stupid. We’ll just have to see.

1See Mara Accettura, “Rachel Whiteread e l’installazione sulla pandemia a Bergamo: ‘Decifrare ciò che è accaduto aiuta a guarire,’” La Repubblica, July 8, 2023.

2See Bernard Berenson, Piero Della Francesca or The Ineloquent in Art (New York: Macmillan, 1954).

Rachel Whiteread: . . . And the Animals Were Sold, Galleria d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea di Bergamo, Italy, June 23–October 29, 2023

Artwork © Rachel Whiteread; photos: Lorenzo Palmieri