A potter since childhood and an acclaimed writer, Edmund de Waal is best known as an artist for his large-scale installations of porcelain vessels, which are informed by his passion for architecture, space, and sound.

Nature repeats herself, or almost does:

repeat, repeat, repeat, revise, revise, revise.

—Elizabeth Bishop, “North Haven,” 1978

i

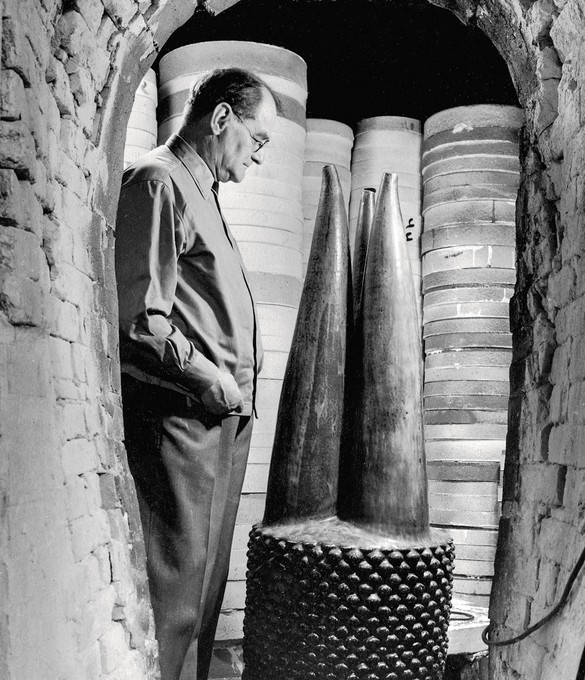

Looking closely at the photograph I realize that you must be tall. I know that slightly apologetic hunch, the way of accommodating objects on tables, a sketch pad, someone else smaller than you. You are in the kiln surrounded by the stacked saggers with that big slightly sinister pot, Kraftens Kerne, standing on the ground in front of you. It reaches your chest and it seems to be looking back at you. We will get back to the subject of totems. Stay with me.

If we are going to get on I need to know how you pace the world. Your stride. So much of your work takes the form of a journey. You write a book for children about the adventures of Kusai, who travels from his home on the beach, through low forest, high forest, across a river, toward a mountain, encountering magic animals until he finally returns home with parrot feathers for his mother’s hat. It’s a little dodgy in its colonial emphasis but the journeying itself is heartfelt. Your ballet is a quest too. There is one stoneware vessel that you created in 1936 which is a walk up to a hill town in France. It is summer and it is dusty. There are scuffles, a tail of a lizard over stones. The track winds through olive groves and orchards and the occasional rows of bean poles. Up and up. The cypresses. And up.

And the town is folded into itself, one house into another, one window, a lintel, a doorstep, the bell tower, a square that leads in three directions, steps. Everything is repeated, plural. And so the movements of this journeying up and round the hillside are a kind of stretching and pausing. A looking round.

“In the South of France we often walked from Cagnes to La Gaude. The road led up across a very hilly, sunlit mountain with forests, canyons, terraced olive plantations, roads, houses and paths, and I have attempted to put the memory of this lovely walk into a substance that not only reproduces but is itself the hard, sunburnt mountain. This is as close as you can get to your subject,” you write.1

And then, because you should never waste a good idea, you take that feeling of a walk through a landscape and keep drawing it, inverting the hillside, doubling one hill on top of another, spinning it on its head, giving it a pedestal, taking that away. The path comes and goes, sometimes a line of intent, sometimes a proper road to the summit. I realize that you walk with your sketch pad in your hand. The “flight and perching of a bird” is how John Dewey described the being-in-the-moment and reflection-on-the-moment. In the Axel Salto archives in the museum there are thousands of drawings, returns, repeats, revisions. Your hands don’t stay still.

We are going to get on.

ii

(I like your name.

Axel and Salto balance)

iii

We have to start somewhere so let’s start at the mouth of the kiln.

Let’s start.

More broken pots. More pots to break. It is Tuesday and early and no one else is in the studio, except the dog who has taken herself to her bed and is snoring already. My kiln is still too hot to be comfortable to reach into and extract the new black-glazed jars I’ve made. The temperature gauge of the vast green gas kiln shows 120 degrees but that doesn’t mean much as the thick kiln shelves and the pots themselves will be much hotter. You don’t open kilns, you crack them. This holds good even if it is several tons of steel, a heavy hinged door.

I crack the kiln. There is a black jar near the arch at the top of the kiln, eighteen inches inside, half hidden behind a flotilla of small bowls. This black is my current favorite glaze, dense, river-stone dense, slightly metallic. I can see that the flame has worked up across the side, so that there is a run, a fluxing, that you cannot control and hope to see. The jar looks beautiful in the shadows.

I’m wearing my heavy red heat-proof gauntlets but I manage to burn my wrist on the kiln-shelf as I reach in to lift it out. It is the wrong weight. The glaze has run off the jar—I leave jagged porcelain on the shelf and bring out a jar with no base.

Two of the seven bowls have glaze that has run in the same way. They are plucked.

For a few hours after you take porcelain out it sings. It settles into the world with high-pitched ticks.

I tally this firing. One extraordinary bowl, donum dei. Three pots for the hammer.

iv

This is our territory.

You write in an early text in 1930 about the end of a firing, the wait for the pyrometric cones to bend that tell you how much heat-work has happened:

If the 1280 degree cone is down and the 1300 degree cone begins to wobble, it is time to stop firing and close the kiln, which then cools for a couple of days. Then comes the long-awaited moment, the romance of the ceramicist, as the stoneware is taken out, scorching, creaking underneath the cooling glaze. The excitement, joy and disappointment of that moment is worth two months of preparation: right there are a hundred ceramic pieces.2

I am going to steal “creaking” off you: I like that. Pots creak as they cool, as they change from one state to another, leave behind their infinite potentiality and cool into this particular thing in front of you. And then you continue and reflect that a

piece of porcelain is either successful or not; it only matters whether or not the vessel is crooked, if the material has a beautiful whiteness, if the decoration stands out nicely and clearly, that is, if the piece is technically good. When it comes to stoneware, a flaw or coincidence can be transformed into something beautiful and maybe point to new directions which will lead to new results. Thus the crackling that was initially a mistake contained possibilities for new ornamentation and effects in the material.3

And I can’t allow you to be so pedestrian about porcelain—my beloved material—but I think it reflects all those conventions about porcelain as perfection, non-crookedness, niceness, clarity, the technics in order. I wish you could read my book on this, the danger of obsession with whiteness, but I’m not sure we have the time. And here we are at the kiln mouth—the place for vocalizing—and you are unpacking the new vessels and examining them and are so absolutely right about flaw and coincidence, that generative spark which takes you off and away toward a denser mottled glaze (the fur of a faun, a weathered rock, the broken colors of a seashell), toward the infolding and unfolding of a form.

All kinds of things can go wrong in a kiln.

I built my first kiln in Herefordshire in the lee of an old yew tree next to a damp barn. I had finished an apprenticeship and spent a summer working with silent potters in Japan. I had bought the kiln bricks from a Herefordshire potter who had gone bust. I had also bought his wheels, his ware-boards, an oak table for wedging clay, buckets and sieves, brushes, rock-hard bags of terracotta clay, jars of oxides, kiln shelves. I counted out £1,000 and he looked relieved.

My first kiln looked like a very small chapel. I used a plan from Michael Cardew’s Pioneer Pottery (1969), a bible of self-reliance, full of tips on how to prospect for raw materials. The kiln was five feet long and four feet wide and I could crouch inside to load my stoneware casseroles, lidded soup-bowls, teapots, tea bowls, jugs and mugs onto the shelves. The arch above my head was a bit wobbly. My chimney wasn’t particularly straight. I had to brick up the front each time I fired and little orange flames would find the gaps and lick.

Kilns work on the principle of directing heat evenly around all the pots stacked on their heavy kiln shelves, and then out of the chimney. Kilns shouldn’t leak, they should contain heat. I built mine so poorly that I found myself awake at three in the morning trying to coax the temperature higher, caulking the gaps between bricks, altering the dampers to see if I could get more pull of air through the kiln, praying.

Gaps in the kiln also meant that it cooled unevenly and damp Herefordshire air would sneak in. And the pots would dunt. They would crack. Sometimes you would discover this when you unbricked the kiln. Sometimes days afterward you would pick up a pot and tap it and it would sound dull, and as you ran your hands over it you would find the lattice work of fine cracks, and another batch was unsellable, unusable.

I tally forty-two firings over two and a half years at the Cwm Pottery, Rowlestone, Herefordshire. Twelve total failures. Twenty mostly wrong. Ten firings with enough green celadon, oatmeal, and black tenmoku glazed pots to sell in the Herefordshire Guild of Craftsmen shop near the cathedral, or pack in newspaper and hawk round my friends in London. Hundreds and hundreds of pots dunted. Dozens chucked over the hedge into the stream below the workshop. I broke several thousand.

Today, a Tuesday thirty-five years later, I pick up a hammer and reduce three pots to shards, fragments.

I think of your ‘excitement, joy and disappointment’. And I know you knew how to break things up, how to start again with fragments.

v

Let us slow down here. We are by the kiln, we don’t have to rush.

Indeed there are so many moments here to slow down and consider that I want to still our conversation.

I think of the photographer Eadweard Muybridge, those percussive stillings of a horse galloping, a man running. If these moments become gradually shorter can we find that exact frame of time when the vessel tilted in the kiln, the molten glaze gave up its hold on the clay body and spread? Can we go back further and further and find det brændende Nu, the burning now? You thought about photography, thought about the recording of transformation, and then wrote about this now, drew it, made it happen.

There is a glorious image you made in 1935:

I am working on a painting that depicts a tray with cups falling to the ground. The painting is a depiction of the burning now, the tense and uneasy but yet strangely enchanted second it takes, from the moment when the cups start to slide until they are shattered against the ground. The falling, turning cups stop in the air for a moment like a bush that grows from the bottom cup that has already burst, but whose shards still stand in the air during the reaction of the moment of the blasting.4

I love this.

Here is time standing still, the world, the body, the breath slowed to a breath-turn. There is nothing you can do to catch this cascade of cups as they fall. Your experience of this moment is both caught in the knowledge of what is happening and has happened, the slippage and the sound of breakage. And it runs backward—“Earlier and earlier, the unraised hand calm/The apple unbitten in the palm,” as Philip Larkin wrote in his poem about a shied apple core missing the wastepaper basket.

Because the broken cups blossom back into the unbroken cups. The burning moment defies the banality of a present or a past tense or a future tense. Transformation is fissile. Objects hold their transformative, burning-now in trust. If you can change you can change again. The smashed cups talk to the clay in the potter’s hand.

I remember writing about a Chinese bowl from the twelfth century:

The bowl was made in Jingdezhen, thrown then moulded with a flower in a deep well, unglazed rim, green-grey with a slightly pooled glaze, some issues as the dealers would say, chips, marks, scuffs. It happens in the present tense and it is, itself, a continuous present of active, dynamic movements, judgements and decisions. It doesn’t feel in the past, and it feels wrong to force it into one just to obey a critical orthodoxy. . . . the act of reimagining it by picking it up is an act of remaking.5

Breaking, dropping, falling cups are an act of remaking too.

vi

And breaking can be such fun. In 1943 you publish Tryk selv dine Billeder, “Print your own images,” a book for children. It is an emphatically, gloriously funny exhortation to keep going. Repetition is the only rule, you write. Could there be anything more liberating?

I have your book in front of me as I write to you. It is big and orange and handsome with an impish-looking acrobat with a top hat in one hand holding another person in midair by the head, limbs dangling. Look at me, they are saying, join in. This is a manual for mucking about.

It involves stamps. Not postage stamps, but the kind you might have used in kindergarten, pressed into ink and then emphatically stamped onto colored paper. It opens with a forest of trees and then three pages of your text. And then here is a green page with all the elements you will need. You are given some limbs for a person and some parts of a horse, four faces, a top hat and a cane, a bowl and a dish, the trunk of a palm tree, some foliage, some broken shapes and a thick black line. And a mustache. A glorious, bad-sort-in-silent-movies mustache.

And so here is a horse and here is a rider. And you are off, galloping, cantering, falling off, falling under, legs akimbo, forward, backward, breathless.

And here are four acrobats. One (highly mustached) is juggling balls. One is balancing objects precariously. Another is standing on their head and holding an ungainly tree high above them. And one sinister gentleman is balanced on the crown of their top hat, two spiky legs waving other hats high above him. Thump go the stamps down onto the page. More juggling balls. More legs. More hats. More is good.

And then here is the kitchen.

It starts in an orderly way. A shelf at the top of the page with fifteen cups. Two shelves mirror each other with bowls. Two shelves with stacks of bowls. A line of seven elegant vases—stamp, stamp, stamp.

And then down it comes. Bowls in midair and dishes clattering everywhere and the vases near the bottom of the page and the walking sticks are involved somehow and the air is full of things breaking apart, fragmenting, becoming shards. You see it. You hear it. You feel it.

One thing becoming something else, becoming other. A burning, breaking, glorious, noisy, now.

Imagine being given this as a child. Imagine this license. You know what you are doing when you say more is more, when you say again, when you say now.

The final page is a deer and it is a falling man, one on top of another, one becoming another, “double nature”: “You are in the world of stamps, in wonderland, it is you who decides everything.”6

1Axel Salto, “Epilog til en Stentøjsproduktion 1929–1937,” Samleren. Tidsskrift for Keramik, Porcelæn og Glas, January 1934, p. 5.

2Salto, Salto’s Keramik (Copenhagen: Det Berlingske Bogtrykkeri, 1930), p. 10.

3Ibid.

4Salto, Det brændende Nu (Copenhagen: Grafisk Cirkel, 1938), p. 8.

5Edmund de Waal, The White Road (London: Chatto & Windus, 2016), pp. 4–5.

6Salto, Tryk selv dine Billeder (Copenhagen: Fischers Forlag, 1943)

Artworks © Axel Salto/VISDA

Edmund de Waal: this must be the place, at Gagosian, 541West 24th Street, New York, September 13–October 28, 2023