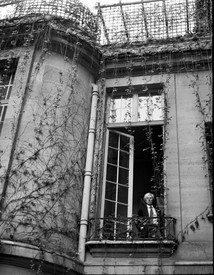

Helen Marden was born in 1941 in Pittsburgh and lives and works in New York and Marrakesh, Morocco. Her group exhibitions include Who Chooses Who, at the New Museum of Contemporary Art, New York (1994); Selections Summer ’96, at the Drawing Center, New York (1996); and Couples Discourse (2006) and Uncanny Congruences (2013), at the Palmer Museum of Art, Pennsylvania State University, University Park. She participated in the Whitney Biennial, New York, in 1995, and the Last Brucennial, Bruce High Quality Foundation, New York, in 2014. Photo: Douglas Friedman

Kiki Smith has been known since the 1980s for her multidisciplinary art exploring embodiment and the natural world. She uses a broad variety of materials to continuously expand and evolve a body of work that includes sculpture, printmaking, photography, drawing, and textiles. Smith has been the subject of many solo exhibitions worldwide, including over twenty-five museum exhibitions. Her work has appeared in five Venice Biennales, including the 2017 edition. She is a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and in 2017 the Royal Academy of Arts, London, made her an Honorary Royal Academician. In 2006, Smith was recognized by Time as one of the “Time 100: The People Who Shape Our World.” Photo: Chelsea Culpepper

Kiki SmithBeing in your house now, Helen, I have a memory of the first time I came here, but I have no idea why I was invited for anything at all [laughter].

Helen MardenWe were having, maybe, a Christmas party?

KSIt wasn’t Christmas. I don’t know what it was. It was a long time ago.

HMI remember you were here right after 9/11—I had had my sixtieth birthday party planned and we just decided to do it anyway because I thought people needed somewhere to go and hug each other.

KSYes, that was a complete lifesaver. I remember that every 9/11, how incredibly important that was. It seemed so frivolous, and at the same time, it was so stabilizing to be in real community.

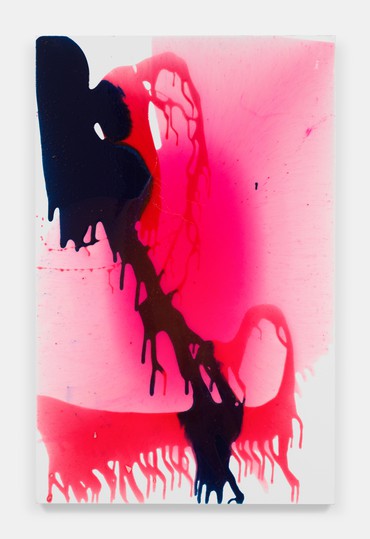

The odd detail I remember was being in the kitchen and above the kitchen you had this fuchsia, bright fuchsia, like Day-Glo pink, dripping down above the stove. It was so radical. And I just went, This is a different brain. When I was young, a friend of my sister’s had an apartment, I think in the Chelsea Hotel or something, she’d spray-painted the walls, and I was so shocked—my reaction made me realize how conservative I was. You know, like, What’s the landlord going to say? Are you going to get in trouble? And I thought, Oh, Kiki, you’re so square. In a sense, when I saw that pink in your kitchen, I had the same feeling of shock. I thought, This is a radical position.

HMYes, we used to have that pink! I painted it with watercolor and I just kept doing it till it dripped down over the stove. Now it’s been painted green, but we had that pink forever.

KSI thought, That’s a special person to investigate now. It was captivating: you’re looking at something that somebody made, and it has some sense to it, but it’s not one that you can discern. And your paintings are like that too. Do you say to yourself, I’m going to use these colors today? Or. . .I mean, you have to make preparations for mixing all that stuff, but do you really plan it out?

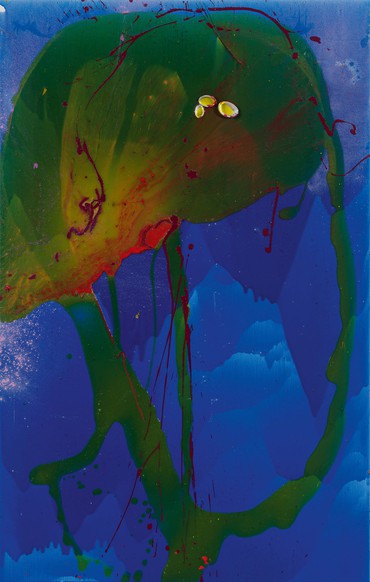

HMDo you know what I do? I sit on the sofa, and I have some color in my mind, and then I sit there too long, and then I jump up and I run over and I stir the resin. And then I pour that color in and jump again and run over, and there it goes.

KSThat’s like an intuitive dance—very much time based in the now.

HMI never thought about it that way. Martha Diamond once told me she always did a mock-up before creating her work and I thought, How strange, I could never do that. I could never sustain my interest to first make one thing and then have to make it again, when in the end it looks like the first thing. No, that’s not how I am, obviously.

KSI noticed, looking at the works that will be in your upcoming Athens exhibition, that there are darker colors.

HMWell, it’s been a—it’s been a lot of darkness here. Maybe that’s why. But while these colors were coming to me, I was thinking, Oh, that’s new. That’s cool.

I also recently had ten or thirteen circular canvases made because I thought it would be a fun shape to try, so I put resin and stuck feathers on them. Then I ran in and found a bottle of ink and just poured it on while the resin was wet. I couldn’t get the color that I wanted to use—I couldn’t get the bottle top off—so I ran back and got this one.

KSThat’s a good color, like sanguine.

HMThen I thought of Icarus—

KSIs that where the feathers come in?

HMYes, and I’m also just generally inspired by the natural world—like you, too, with your depictions of animals. I’ve included seashells because they’ve been a presence all my life; I remember collecting them with my mom. And I guess they mean a certain strength, but also they’re fragile.

KSThey’re also luminescent, like your paintings. If you look at the little bottles, the shells, they have this shine—

HMDo you think that’s cheating?

KSNo [laughter]. I don’t think you can cheat.

HMWell now I can say Kiki told me it wasn’t cheating.

KSI don’t believe in cheating.

HMOh, good.

KSI collect shells too. I collect shells and rocks. I went to Ireland once when I was sixteen and I asked my mother, What should I bring home, and she said, Just bring me a rock. Back then we didn’t have much so we valued natural objects we could just find.

HMMy mother would collect all kinds of rocks from walking around. So I grew up with halls of rocks.

KSYeah, we had shelves of rocks and crystals. My mother was deep into crystals and rocks. I have rocks that she had from before I was born. And when I met my husband, I took my assistant and we went into my bedroom and I said, We have to hide all of these rocks [laughter]. I said, This guy’s going to think I’m a total crazy person. And we hid them in the radiators.

HMAnd did he find them and then he knew you were crazy?

KSNo, I think he’d already figured out that I was crazy.

Before that, another time I had about eighteen birds living in my bedroom. And somebody said, You know, Kiki, if you want to be in a relationship, you have to make concessions. And I was like, What do you mean? [laughter]

HMYears ago I had bats living in my loft with big banana plants and things so the bats could hang on them. People pointed out to me that maybe someone didn’t really want to come back to your place and find bats [laughter].

KSBut honestly, I think nature is in and all around us. If you look out the window here, you’re practically in a jungle, you know? Everything we do is in relationship to nature. It’s the most powerful thing there is.

HMHow did you begin creating animals in your work, like your wolf? Where did that come from?

KSI was invited to MassArt [Massachusetts College of Art and Design, Boston] in 1994. And I went to the Peabody Museum and made drawings, and then I made life-size etchings from them. Basically since then, all the animals I’m making originated from the drawings I made in ’94. It’s like having a repertory theater or something like that, you can kind of pull them out.

HMI like that.

KSDo you feel like you have that with color at all?

HMWell, yeah, I do—

KSLike a palette you return to.

HMI think after the darkness, I went right back to using the magentas and everything—my repertoire. I was in my studio looking at those dark works, thinking, I don’t know where that came from [laughs]. Like I said, things were difficult and that dark just came out. I didn’t think it through first; I don’t know if you’ve noticed, I’m not an intellectual.

KSBut it’s not that—it’s not about not being intellectual. It’s that when you have access intuitively to things, it’s because you actually have synthesized them and you know them and you can access them without cognitive effort. One of the nice things about being an artist is you don’t have to use language. You know, language can be a great gift—

HMBut it can be a big hindrance. One of my favorite quotes by Robert Rauschenberg is “We all know by now we’re serious. We don’t have to act like it” [laughter]. I agree, Kiki, and with many artists we know, there’s a certain depth of knowledge. They don’t have to go over their work and explain to themselves and the public, This is this and that.

KSAnd also, someone like you, Helen, has seen a tremendous amount of the world, having spent time in Morocco, Greece, and many other places. And so, by being and seeing, you can utilize your experiences in your work. I’m a reluctant traveler, a complete homebody, but when I’m somewhere new it often expands my repertoire.

HMYou had that great show at the Slaughterhouse in Hydra[, Greece]. And there were all those tables, you invited everyone for dinner. It was so lovely. When was that?

KSRight before the pandemic, the summer before. That was a very nice experience. I like that—if you get to go make something for someplace special, it’s not just, I don’t know, interchangeable with every other place in the world.

HMI have a vivid memory of being in Hydra with you. My daughter Mirabelle took pictures of us in the water—

KSYes! And you had a red bathing suit. I was really impressed by that. See, you’re always impressing and encouraging me with color [laughs].

When I was young, I made things in color and then I stopped because I felt it was too personal. It felt too vulnerable. Because someone could come and say, Why did you use that color over that color? And I thought that’s a little scarier than I can handle in life, to be asked questions like that [laughter]. And I really used practically no color for about twenty, thirty years, and then I started using color in more of a factual way: you know, this is the color of blood and this is the representation of the nervous system. So your work to me is so liberating and radical because you know intuitively what you’re doing and you’re just moving. I thought, I can use color, nothing bad is going to happen to me [laughter].

HMThe color witch won’t come and get you [laughter]. But in all seriousness, there’s a big prejudice against color, and especially against women artists using color. It’s like a big sign of their not being good enough or smart enough. I don’t know if it’s just American; I guess it’s European too.

KSWell, Europeans are—they don’t know that many women, so it’s not a problem [laughs].

HMYeah. I look at all those Aboriginal painters in Australia and I just love the color and the dots, and you know what they’re wearing, it’s all color.

KSIt’s really true that women have been trivialized for using color. Many of the female painters from the twentieth century were marginalized because color was and is considered frivolous. Likely because it’s attached to nature.

HMNature is women.

KSYeah. Well, it’s the same thing. You know, look at those peonies and stuff. Pure frivolity [laughter].

HMHere we are, frivoling away [laughter]. Frivol, frivol, frivol.

Artwork © 2023 Helen Marden/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Helen Marden: Agape/Aγáπη, Gagosian, Athens, September 21–October 21, 2023