Amie Corry is a London-based writer and editor. She was senior editor of Other Criteria Books from 2014 to 2020 and is director of publications for the artist Do Ho Suh. Corry contributes to the Times Literary Supplement, Burlington Contemporary, and other publications, and in 2013 she coproduced a pioneering audit on gender equality in the London art sector.

In A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers (1849), Henry David Thoreau observed that scenery ceases to become sublime when “the imagination is no longer encouraged to exaggerate it.”1 I’m reminded of Thoreau’s words on viewing Jennifer Guidi’s latest paintings, spectacular mountainscapes in a more representational mode than this American artist’s work of the last decade. Traversing a delicate line between the sublime and the abstract, here Guidi teases at the possibilities of landscape painting, providing space for the viewer while communicating something of the world’s expansive mysteriousness. Recently the subject of a solo exhibition, Mountain Range, at Château La Coste, these paintings are, first and foremost, as the artist explains from her LA studio, “interior landscapes,” landscapes of the mind.2

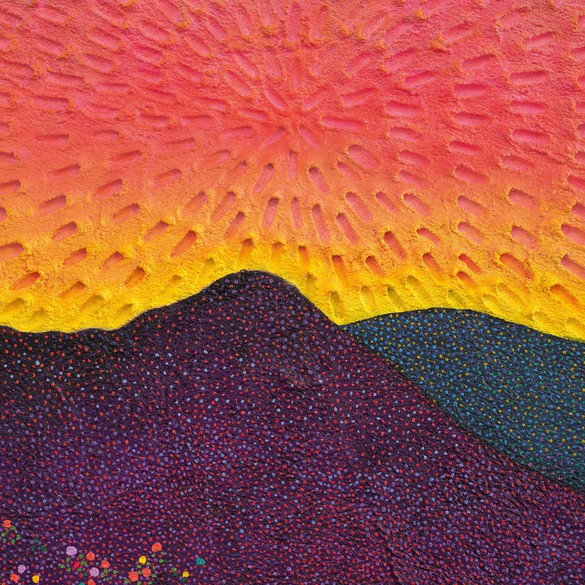

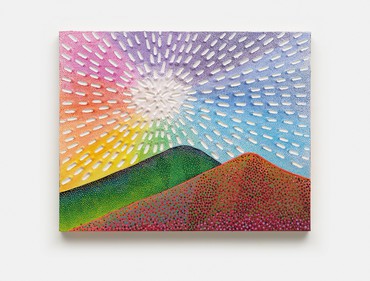

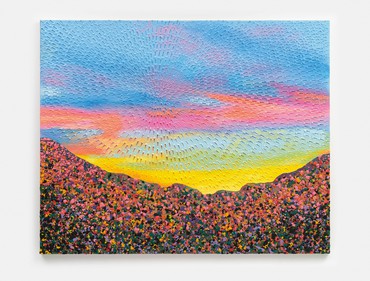

The new body of work features Guidi’s signature technique of mixing sand with pigment, oil, and acrylic to create rich, textured surfaces. Then, in a now well-documented process, she uses a dowel to gouge regularly spaced incisions in the sand in mandala-like patterns. In the La Coste work, Guidi generally reserves this technique for sections of sky, while her mountainous landmasses surge unevenly from the surface, bolstered by additional mineral matter—rocks and pebbles. It seems to me that these developments further the complicated push and pull between concealment and revelation, addition and negation, effected by the sand paintings. What remains consistent is Guidi’s interest in painting as an ardent ode to the power of color and humankind’s ability to harness it.

The undulating, vine-covered region of Provence is famed for the suffused light that mesmerized the likes of Pierre Bonnard and Henri Matisse, both important influences on Guidi. This scenery provides a very literal backdrop to the exhibition via the mediation of La Coste’s Richard Rogers Gallery. This pavilion, the late British architect’s final building, comprises a heavy orthogonal rectangle of concrete and orange-painted structural steel, which cantilevers dramatically out from a Luberon hillside. It is a radical proposition, a feat of engineering that both disrupts and pays homage to its surround. The marriage with Guidi’s vivid, almost prototypical landscapes proves fascinating.

Within the pavilion, Guidi’s canvases, all horizontals as befits their subject matter, not only hung on the walls but in the case of one pair were suspended from the ceiling to carve up the space, riffing on the modularity of modernism. “I like how art and architecture can come together to create a particular experience,” Guidi notes, explaining how the intervention in Provence took shape in her Los Angeles studio: “We designed a hanging system so the paintings are presented back-to-back. I’m very excited by it. I really do have to feel inspired by architecture. Richard Rogers’s building feels suspended in the mountain and then I’m suspending my mountain paintings in the center of the room.”

To Paddy McKillen, the man responsible for transforming Château La Coste from seventeenth-century Provençal vineyard to world-class art and architecture destination, featuring the work of Louise Bourgeois, Tadao Ando, Alexander Calder, and others, the connection was immediately obvious. McKillen describes being struck by one particular work on his first visit to Guidi’s studio: “It had a beautiful vivid pink that reminded me of Richard, who loved strong colors and who often wore bold pinks, blues, greens, and orange, like we see at the pavilion at La Coste. The painting itself was stunning and the link with Richard struck a chord.”3

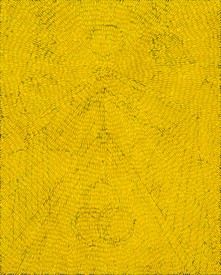

Guidi was interested in the way objects interact with space from a young age: she remembers obsessively switching the furniture around in her childhood bedroom to achieve the right configuration. Recently, she has been curating, a form of arrangement in itself—a virtual exhibition at Massimo De Carlo Vspace in 2020 featured work by Lucy Bull, Wyatt Kahn, Ugo Rondinone, Brooklin Aboubakar Soumahoro, and Guidi herself—as well as playing around with the environments in which she exhibits her painting and sculpture. In Gemini, her solo show at Gagosian on West 24th Street, Manhattan, in 2020, a vast triangular opening bifurcated a wall between two galleries. A disc-shaped yellow sand painting was suspended from the apex of the triangle, which provided a dramatic sightline through to a pair of serpentine forms flanking another disc (a three-part painting titled To Protect and Hold You Up, 2019) on the farther wall. The pyramidal passage transformed the space into something like a solar temple, recalling the unrealized ambitions of the early modern Swedish artist and mystic Hilma af Klint, a key figure for Guidi, to present her abstract paintings within a specifically designed spiritual space.

Architecture also plays an overlooked role in the formal development of Guidi’s practice. Before her move to abstraction over a decade ago, she made photorealist paintings based on photographs she took in and around LA. Her architectural photography features colorful housing blocks, their shutters and brickwork creating exquisite shadow patterns in the languid California sun. It reveals a deep engagement with the interplay of light and weight as they are affected by the structural environment, and a foundational interest in concrete, a primary ingredient of which, of course, is sand.

Guidi’s photorealist work preceded a revelatory trip she took to Morocco in 2012. There, she became absorbed with the patterns of stitches she found on the backs of traditional Berber rugs and, again, began photographing them. This led to the conception of her Field Paintings—neutral-toned canvases bearing rows of small white marks—which debuted in 2014. “Even though I loved color and form and shape and all those things that make up representational painting,” she tells me, “I wanted to clear that out, empty that out, so there was a very purposeful thought in taking color away and working with white, black, and beige.”

The notion of “emptying out” relates to the integral role that meditation plays in Guidi’s practice, which involves durational repetitive motion, almost a physical chanting. The early Field Paintings were also in conversation with the work of abstract artists such as Agnes Martin, whose meticulous grids and lines foreshadowed the advent of a more industrially minded Minimalism.

I suggest to Guidi that Minimalism’s interest in removing the decision-making elements involved in an art practice feels, in some respects, contradictory to her impulse to generate pattern and movement. The Field Paintings, for example, are not quite blankets of solid monochrome but contain squares and rectangles in different shades. “Yes, I think that’s right,” she concedes. “In terms of my internal journey, there was more going on than just an emptying out.”

Guidi was drawn to sand, which she continues to experiment with in the new paintings, for both its material and its symbolic properties: “Seeing sand used as a material in the work of painters like Braque, Picasso and Kandinsky always intrigued me,” she explains. “It connects to the idea of paint as a pigment, a powder, but from the earth. There’s an affinity there, but then sand has a more granular consistency.” To begin with, she mixed sand into oil paint to create a rough-textured surface. Further experimentation coincided with her move toward abstraction: “I was painting these repetitive dots and I was at the beach one day and I found myself thinking: ‘How can it just be sand?’ When you draw in the sand at the beach, it’s such a particular feeling, but I also wanted to capture the texture and the surface. I was thinking, ‘How can I make this a painting and not have to rely on anything else?’” The particularity of that feeling is relatable in ways that separate it from the mystique of pigment, turps, and canvas. Guidi notes, “Not everyone knows what it’s like to work with paint, but for the most part, everyone’s gone to the beach, everyone knows how sand feels against the skin.” Ultimately, it is sand’s ability to succumb to the pressure of touch and weight, its extraordinary heaviness as well as its granular delicacy, that make it such an apposite material in Guidi’s hands.

For years, Guidi has been photographing the mountains and skies, as well as the buildings, of California. These images form a vibrant library of source material for the paintings at La Coste. The landscapes are not direct portraits but rather, to return to Thoreau, vessels that encourage mental exaggeration. There is something playful about Guidi’s engagement with the landscape genre and she exhibits little interest in decentering human presence. The green hillside in the taxonomically titled Miracles of Nature (Painted Natural Sand, Blue-Pink-Purple Sky, Multicolored Mountain, Black Ground) (2023) is dotted with hot pink, orange and lilac, aqua and cerulean blues. This teeming mass populated with color speaks of sunbeams hitting windows, cars, and buildings, as well as of coral reefs and jostling species of flora. It addresses our relationship with nature, how we intervene, capture, and respond to it. While the painting’s obvious ancestry is Neo-Impressionism and the techniques formulated by Georges Seurat, Guidi’s landscapes feel very much of the contemporary moment. That said, for inspiration she still returns to Bonnard, Paul Cézanne, Vincent van Gogh—artists bound to the region in which the Mountain Range paintings have found temporary home. McKillen recognizes this too: “The works themselves are mesmerizing and uplifting; so appropriate in a gallery that overlooks the rolling hills of the Luberon, not far from the St.-Victoire of Paul Cézanne.”

Much is made of Guidi’s interest in color theory, and faced with her giant canvases demarcated by horizontal fields of color representing mountain and sky, it is admittedly easy to think of Michel Eugène Chevreul’s 1839 principle of “simultaneous contrasts,” which posits that when the eye apprehends a color it automatically produces an afterimage of its complementary hue.4 But at heart, Guidi’s decisions are instinctive, governed by mood and moment, by the world as perceived from the perspective of the body rather than an objective formula or system. I ask what governs the location of the central point from which the gouges of sand emanate: “Once I trowel on the sand and I try and find that spot, it’s just what feels right. It’s not measured or calculated,” she affirms. “The center point on the mountain paintings is already established because that is where the sun or moon would be; but in the other mandala paintings it’s always to the left for the most part. My initial intention was that if you were a viewer looking into a mirror, that central point would reflect your heart center.”

Guidi thinks seriously about the viewer’s experience and about how art might intercede in an overstimulated world. Color remains her central vehicle: “I think we pay attention to it,” she says. “Color is something that can stop people from doing what they’re doing in that moment.” I ask whether her fiery mountainscapes include a note of warning about the places we’re heading toward. Guidi ponders this. “Maybe it’s not a warning,” she says, “but it’s a way of communicating the need to slow down, to look, which I think people do when they really take notice of something, to experience something outside of themselves, or outside of their phones, even if they’re going to take a picture of it!”

I’m reminded of the words of one of Bonnard’s key models, the gallerist Dina Vierny, who described the painter encouraging her to move freely around a space while he worked as opposed to sitting still. “He wanted me to walk all the time.” Vierny recalled in a 2005 interview. “Why? He never said. I didn’t push, because every artist has his own rhythm, and no one else can step into that rhythm. His rhythm was color.”5 Vierny’s comment suggests an artist thinking beyond a fixed viewpoint toward something elemental.

Guidi’s Mountain Range paintings have a very particular rhythm, one that flits and darts as the eye hooks onto an aperture, a rocky outcrop, or a shift in tone while absorbing the whole. “When you’re in front of them, there’s an optical illusion or you can feel the vibration,” she remarks. “That’s something I like to experience and I feel like if it’s having that effect on me, it’ll be doing it for someone else.” All of this reinforces the sense that Guidi is an artist of instinct and impulse. Her sand paintings are fed by feeling rather than a desire to record. Her titles—As I Look into You I Begin to See Myself (2019), for example—also speak to this. Indeed, there is a lot more storytelling going on than might immediately appear: colors peek intermittently from the gouges of sand, hinting at hidden layers of paint; many of the works bear underpainting—symbols, marks, gestures—that are entirely covered by the sand-and-paint mixture.6 There is an elasticity to the reading of these paintings that speaks of movement, connection, and impermanence (unsurprising given Guidi’s interest in Tibetan sand mandalas).

As such, I’m interested to hear how she feels about the paintings in their finished, static state; the making process is so intrinsic to this work, worn so literally on its surface. “Well, being in the painting is very different from stepping back when it’s finished, yes. Sometimes I step back and think ‘I love this’ and then there’s times where it doesn’t work and I’ll put it over on a different wall and try and figure out what it is it needs.” Ultimately, though, Guidi says she does not struggle to detach herself from the making. “It’s the power of looking,” she says.

1Henry David Thoreau, A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, 1849. Available online at www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/4232/pg4232-images.html (accessed June 15, 2023).

2All quotations of the artist taken from conversations with her in May 2023.

3All quotations of Paddy McKillen taken from an email conversation with him in May 2023.

4See Michel Eugène Chevreul, Principle of Harmony and Contrast of Colors and Their Application to the Arts, 1839 (Eng. trans. Charles Martel, London: Longman, Brown, Green and Longmans, 1855).

5Dina Vierny, quoted in Barry Schwabsky, “Pierre Bonnard: His Rhythm was Colour,” Tate Etc. no. 45 (Spring 2019). Available online at https://www.tate.org.uk/tate-etc/issue-45-spring-2019/pierre-bonnard-his-rhythm-was-colour-barry-schwabsky (accessed June 15, 2023).

6In 2019, Guidi exhibited a series of drawings in the David Kordansky Gallery booth at the FIAC art fair, Paris, based on Ancient Egyptian iconography. She describes this work as “satisfying” because, although she sketches continually, “it’s rare for me to sit down and make a finished drawing.”

Jennifer Guidi: Mountain Range, Château La Coste, Le Puy-Sainte-Réparade, France, June 20–September 3, 2023

Artwork © Jennifer Guidi