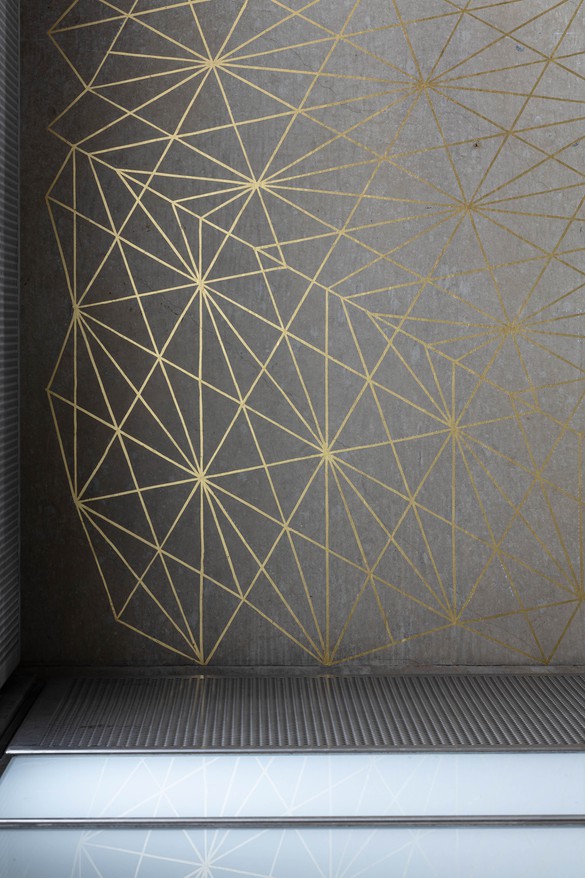

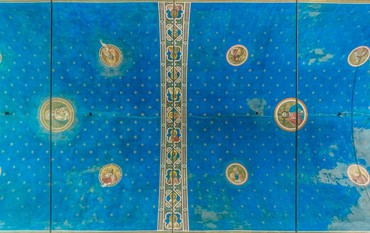

Richard Wright is best-known for his painted and gilded works applied directly to walls and ceilings. His pieces, which are often transient, charge the spaces they inhabit with a range of forms, from baroque ornamentation to constructivist patterns. In recent years he has produced commissions for numerous public spaces and institutions, including the Tottenham Court Road (Elizabeth Line) station, London (2018), the Queen’s House, Greenwich, London (2016), and the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam (2012). Photo: David Ersser

I

In 1984 I dreamt of a painting. Or more particularly of a landscape with two figures (which would later become a painting). In the gloomy translucence a figure lay outstretched on the ground, with another figure crouching over it. In the right hand of the crouching figure there was a saw (this was a bow saw like the one I had used to cut firewood that day). In the left hand of the crouching figure there was an antler; this was being cut by the saw. The antler was attached to, and growing from, the head of the outstretched figure. The outstretched figure had an arrow sticking out of its left eye. On the ground there was a bow and some arrows. Behind the two figures was a soft landscape (hills, trees, sky). To the left there was a dog sitting upright and looking at the action taking place in the hands of the crouching figure. The next day I got up and made a drawing that would become a painting (the painting was to measure 5' x 4').

Some months later I was on a bus in Edinburgh reading the New Edinburgh Review. I was surprised to see an image of my painting above some text. I was more puzzled to see an image of another painting next to it. This second painting bore striking similarities to my own. The painting was by Piero di Cosimo: it had been known as The Death of Procris (c. 1495) but was latterly retitled A Satyr Mourning over a Nymph. I don’t remember much about the text, but I do remember that it was a “positive” review (art-historical references always gratify the cultivated reader). What was truly surprising about all this was that this was a painting that I must have walked past many times, but one which I had no recollection of ever having seen. I had spent many days in the National Gallery, but I had no memory of this work at all and its existence was completely new to me.

That night I got on the bus to London and the next morning I was standing in front of the painting itself in the National Gallery. I wished I had looked at it before because it was haunting, beautiful and I could have learnt so much. My painting, on the other hand, showed more the influence of Picasso’s classical period but was crude and inarticulate.

Dreams can be like this sometimes, so flawless and perfect and you wonder where it all came from, the exquisite detail. But so much of this dream clearly emerged from a painting that I did not know. I must have taken this in at a glance without registering any aspect of it. This reveals just how completely a painting can condition vision, but also how secretly this can take hold. I have a reproduction of this work in front of me now and even in this form it is beautiful (utterly charming), but the painting itself is something quite different. It holds something more, a presence that induces a magnetic state and fills me with longing. I feel the painter close to me. Those waves of air, his breath, touch my face and move through me. From his hand to my hand—I am charged with urgency—I must work. The painting feels like it was made in a world that is not this world. This is to do with a kind of perfection: a perfection that endlessly unfolds like the perfection of dreams.

Delacroix said that you should be able to draw a man falling from a window on the fourth floor by the time he hits the ground. On the surface of it he is talking about facility, but perhaps in a few words he comes close to the very heart of painting. Painting is an act that connects reality and consciousness. It is more than a collective codification of signs. It is a performance that awakens the delirium of vision. Drawing describes the mind in the act of seeing, but this action comes before consciousness. It is only through touching this concrete world that I can leave myself. The silence of things is disturbed into vibration. The task is not conceived, it is not understood; it is lived. The painter goes out into the world and momentarily changes the order of things. The hand has grown to be part of the tool and the tool has grown to be part of everything that surrounds it. If there is knowledge here it resides in the muscles.

For Leonardo the first principle of the “science” of painting is geometry. In his notebook he writes:

If you were to say that the contact made on a surface by the very tip of the point of a pen would create a point, this is not true. Rather we would say that such a contact as this would actually be a surface around a centre and that centre is the location of the point. And such a point is not of the material of the surface. If all the points that are potentially in the universe were to be united—should such a union be possible—neither they nor a single point would compose any part of a surface. And given, if you were to so imagine it, a whole composed of a thousand points, and dividing some part of this quantity by one thousand, it may fairly be said that this part will be equal to the whole. This may be demonstrated by zero or nothing, that is to say, the tenth figure in arithmetic.1

When you look hard at something it disappears. The point is there is no point and this is the place where painting begins. Unlike speaking or writing, painting emerges not from the mind but from the mud. The very tip of the pen, the exact place where I touch the material of things, is nothing, but at the same time it is the concrete point between the senses and the seeing world. Its articulation permits an ecstasy of presence: a softening of the boundary between an inner and outer. One becomes the other and the other becomes one. The veil between this world and the eternal world is permeated: the solid flows through me. I see the future and I see the past.

In his essay “Eye and Mind,” Maurice Merleau-Ponty observes that things arouse in us a carnal formula of their presence:

I would be hard pressed to say where the painting is that I am looking at. For I do not look at it as one looks at a thing, fixing it in its place. My gaze wanders within it as in the halos of being. Rather than seeing it, I see according to, or with it.2

The air shares materiality with me and it is within this air that the painting exists. Without this air the painting cannot be, but you cannot photograph the air: the edges of its solidity open inward toward nothing.

II

And let the helm and steersman of this power to see be the light of the sun, the light of your eye, and your own hand.3

Cennini tells us that he learnt from the hand of Agnolo di Taddeo (Agnolo Gaddi). Agnolo learnt from the hand of his father Taddeo Gaddi. Taddeo, in his turn, learnt from the hand of Giotto. Giotto of course learnt from the hand of Cimabue, if we are to believe Vasari (this is disputed). From the muscles of the teacher to the muscles of the tyro, the body is given to the task. Painting is not only the brush and pigment; painting is a way to live and Cennini’s book Il Libro dell’Arte is a manual that every painter should read and not just read. A little book of cosmic Minecraft that tells you how to make the universe from spittle and dust. But so much more—like a year on Walden Pond—it might give you a hint on how to become what you are.4 Painting is an attitude toward things, an austere philosophy, and the decision to be a painter is like the decision to be a Sufi: it is not something you can choose; actually, it chooses you.

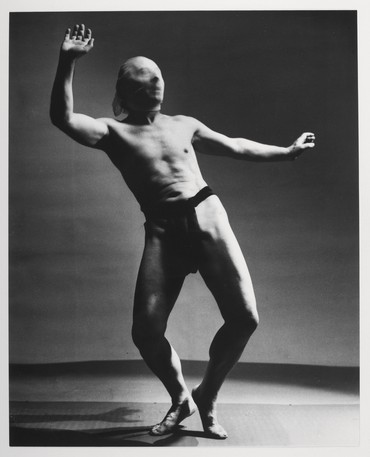

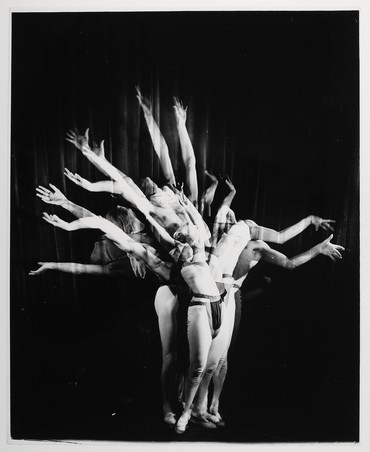

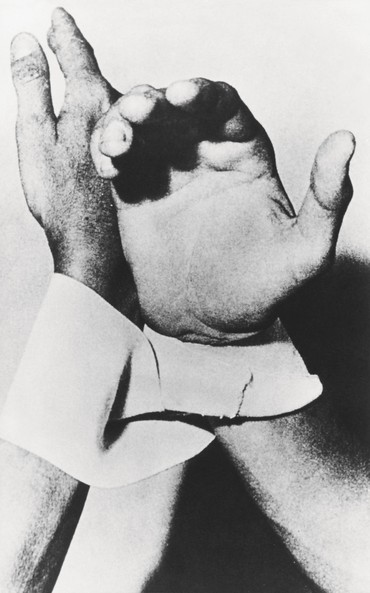

Étienne Decroux—from whose hand Marcel Marceau learnt his craft—tells us that you should marry the craft as you would marry a person. Decroux, the inventor of corporeal mime, studied the art of theater like no other: a devotion, beginning with diction and ending in silence, refined through decades of practice in perfecting a lexicon of minimum movements of his body. All this was not for its own sake, not for the sake of art, but for the sake of extracting from “the world—where things are hidden—the things that are hidden within things.”5 Along the way he asks: what can I say without words, what can I say without thoughts. His body does not copy life; it lives life in a purified form. Movement does not represent things, it presents them. Words cannot replace this action; only the body can prepare for the incarnation of things and this takes time: “These things, seen and even handled, have passed, little by little, to the back of my head, made their way down to the back of my arms and arrived at the ends of my fingers where they changed my fingerprints.”6

Practice is a process of becoming: I work the material and the material works me. I have tended to prefer the word “performance” to the word “craft” because “craft” has been misused and demeaned. But craft speaks of something particular. Duchamp wanted to get away from the artist’s paw and there is no doubt that one of the central themes in contemporary art is the increasing distance between the artist and the making of things. Craft is widely associated with mere facility: something quaintly mindless and technical, which is somehow separable from the higher practice of art itself. I can see why this type of thinking may facilitate theoretical development and aid the promotion of elitist concerns, but for me it is mistaken. Craft is not just a tradition of redundant skill that has largely become a pastime. Craft is an embodiment of an attitude toward everything. Painting does not require a brush or paint. Painting is the craft of seeing; it is an attitude toward touch in which method is everything. There is nothing else.

Sometimes a painting idea is no more than a meeting between a quantity of material and a quantity of action. In repetition the hand and eye are joined to the world. It interests me that repeating something can effect a kind of sedimentation, to use Robert Smithson’s thinking. This is a musical idea related to rhythm or measure. But sometimes the measure is the measure of nothing. For every action there is an equal and opposite reaction and even an apparently idiotic and meaningless gesture, like taking a vow of silence or filling up a glass and emptying it, can change the order of the world.

In 2008 I began a project with the title one thousand circles. I painted the first circle on 24 May that year and continued to paint or draw a single circle each day until 17 February 2011 (1,000 days). The circle, mother of polygons, is universally symbolic and symbolic of universe. But what interests me about the circle is that it is a kind of fact (a finite domain equal in all directions). The statement “one thousand circles” is somehow definitive. But making one thousand circles is something quite different. In this respect the title becomes something votive: a sort of promise. This commitment or conscientiousness was largely unobserved and unmoderated and so it became a secret vow, or a promise to the universe.

It is noteworthy that Vasari should choose the figure of the circle in his tale of Giotto’s audacity and brilliance. Had Vasari described Giotto as drawing a beautiful face, horse, hand, etc., there might have been some speculation as to the merit of his judgment. But a perfect circle needs no speculation for the very reason that it is perfect. “This is enough and more than enough” was what Giotto is supposed to have said when he drew the circle to demonstrate not only that he was a master of his craft, but also his deep insight in understanding that the circle, the simplest of all figures, was the most rigorous of all tests for the unaided draftsman. Vasari did have a tendency to get carried away, but this observation is not without value and committing myself to this ordinance was definitely connected to this. In general, paint does not want to be a painting: paint wants to roll about all over the floor and stick to your clothes. The body also does not want to play its part (it would prefer to look at its phone). The task then is one of empathy and self-control. Discipline is both an act of will and an act of obedience.

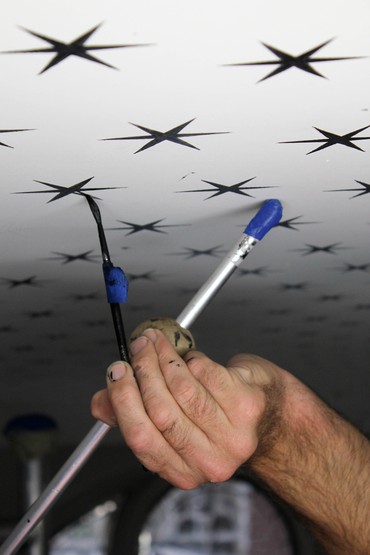

Training to be a signwriter was a turning point in my development. At the beginning the master held out his hands with his palms turned upward and said, “Show me your hands.” I placed my two hands on top of his and he gripped them. He passed his fingers over my palms and fingers and released my hands. He said, “You’re a nervous cunt like me. No bother, you’ll make it!” Those were his words. It was the way a man of his generation would speak to another man—tender and brutal—and it seems to me that the exact words are important. He knew what he was talking about; it had taken him eleven years to learn his trade. He could paint over twenty alphabets freehand from memory (including Helvetica). I later realized that he wanted to be sure that I did not have sweaty palms. I spent much of the next two years covering boards with two letters, “s” and “o,” between “snapped” chalk lines: sanding down, repainting, and covering again with freehand lines of Ss and lines of Os (the boards were 6' x 2').

This was the start of a more objective or even abstract attitude toward material: what I might call “conscious superficiality.” I had spent fourteen years studying and practicing the most minute gestures and inflections of painting’s attitude: how painters show themselves to be painters, from the Egyptians to Georges Braque via Pietro Lorenzetti. But signwriting showed me something else. It was a kind of release: the paint wanted to be “as good as it looked in the can,” to borrow the words of Frank Stella. This finally connected me back to pure plastic art and I did get away from the “artist’s paw.” Painting started to feel more like construction: placing one object on top of another.

For a long time, I had been preoccupied with the idea that painting could only have real existence or value if it declared itself to be over. This probably has its roots in a disillusionment and rejection of the empty gestures of 1980s painting. But it was also something much more personal. The problem with painting was not just that you could not do anything without it being part of something that had already been done, but that what had already been done was impossibly disconnected from my world. It seemed that in order to paint one had to pretend to be a grand figure from another era (smoking cigars and wearing a silk dressing gown in the street). Pop had begun something that it was hard to come back from. Of course, this also had to do with wanting to liquidate the so-called bourgeois inheritance (of paintings over the fireplace, etc.). But more than this, there was a sense that painting could not engage. Gerhard Richter used the word “inadequacy” and doubt seemed to be a necessary part of the activity. For a while it seemed impossible to even paint at all. Painting, like praying, had become a hard thing for an intelligent person to do, or at least to admit to.

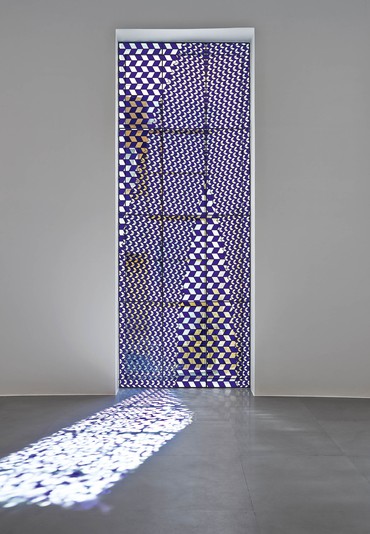

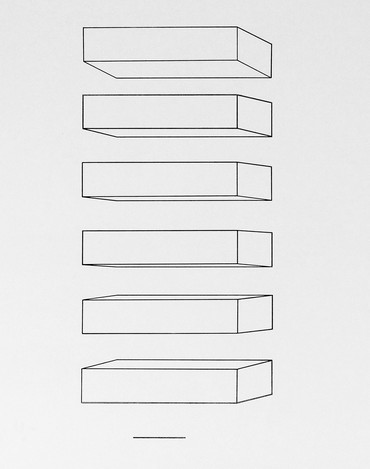

When I stopped painting on canvas I had the feeling that I had stopped painting altogether. I began to think of painting as way of acting on the world. I thought more about ordering things than expressing things, and it seemed plausible that moving a table from one side of the room to another was as much painting as depicting a jug of sunflowers. This was connected to the idea that a painting could just be a “thing” as opposed to a sign. But my thinking was also close to that of Donald Judd in “Specific Objects” when he speaks of the notion of three-dimensionality as being neither painting nor sculpture.7 I moved away from representation: away from virtual pictorial space and toward actual space.

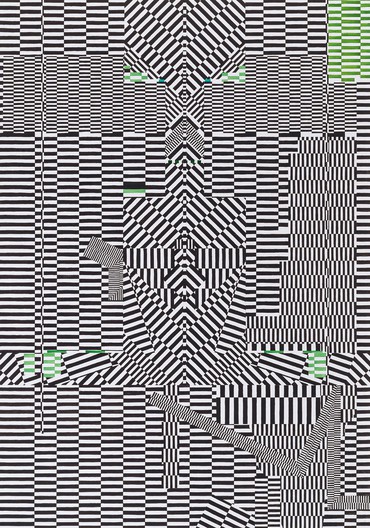

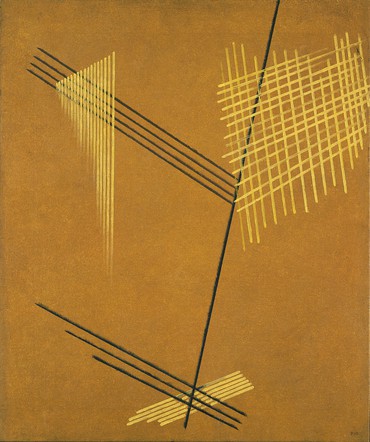

Actual space seemed to be the locus of possibility. I have said this before, but for me a painting should be like a word for which there is no synonym. Like Decroux’s corporeal mime, painting does not represent; painting is the thing itself. In this condition it has the possibility to remove itself from the world of signs and become part of everything else: to be as ignorable as it is interesting. This provisionality allowed the possibility that painting may not have to directly address the subject at all: that a journey does not necessarily need a destination. This sense that painting could disappear into things also made a connection for me with the ideas of artists like Mondrian and Rodchenko and the formal qualities of their work. “There is a world that is not man, that sends man no signs, that has nothing in common with him.” The work of Mondrian and Rodchenko is oriented not toward the human story, but toward pure forms, eliciting a meditation on the act of seeing, rather than offering “meaning” in the sense that we might expect.

Rodchenko denounced easel painting, rejected the convention of self-expression and moved toward the applied arts. There was something in this for me and I was drawn toward the language of graphic design and ornamentation. The idea of style seemed to offer a kind of resistance to the expectation that painting should carry existential resonance (an expectation that I thought of as regressive and reactionary). I was also hugely interested in art from the East and the idea that art could function outside the expectations of Western melancholic mystification. It was style versus tragedy and all this had its resonances in the dialogues of so-called postmodernism, which in the art context, for me, could have been designated as “post-Pop.” Pop was the complete death of high art, but the post-Pop product was just too consumer oriented. I actually felt and still feel that painting ought to have a different kind of responsibility. I did not want to tell people how they should live, but I did want to remind them that they are here.

I was not so much thinking about more established conceptual practices like that of Sol LeWitt as more fragile positions of artists like Chris Burden or Yves Klein. Of particular importance were the Neo-Concrete artists like Lygia Clark, who seemed to put the body in the center of the work: “The rectangle in pieces has been swallowed up by us and absorbed by ourselves.”9

Provisional activity or performance, if you like, arrived as some kind of solution, permitting painting to both exist and not exist at the same time. The temporary nature of the work had the effect of placing it in the domain of time and repositioned the subject within the work itself. It stops being about images and starts being about being. Time started to be the principal material of my activity and painting became a way of moving.

I approached the built world, indeed everything around me, as if it were already a painting or a sculpture. I was struck by that thing that Isaac Babel said: “A phrase is born into the world both good and bad at the same time. The secret lies in a slight, an almost invisible twist. The lever should rest in your hand, getting warm, and you can only turn it once, not twice.”10 This was the kind of thinking I tried to bring to the work. I tried to begin with one thing and restrict development to one or two operations (after that there was just too much counterpoint).

There was an intentional lack of depth—a refusal of the picture space—and it all became much more about the surface of the world. I began to see individual touches or gestures as being like John Latham’s minimum events: markers of presence, markers of time and space—events remembered and measured. But I wanted something less “fine art.” It interested me that in graphic design a kind of degradation occurred with reuse and overuse of symbolic material. What had been content in another context was somehow emptied out and hollowed into stylistic effect. If the dentils in Ionic entablature ever had any symbolic content, their displaced ornamental use has caused them to become mere surface activity: they have gone back to the world of things. But in this condition, they also seemed to offer a kind of latency, a potential to be filled or reactivated. This has something to do with trace: a dormant attraction or an inheritance of another kind of memory of archetype and the touch of past use. This reactivation is the start of something.

People have often asked me “why painting?” and I can only say what I always say. Painting remembers how it got here. Brâncusi said that sculpture is the direct cutting of stone and I am guessing he was making a distinction between this activity and others that might be called “modeling” and “construction.” The stone pillar remembers the mason in a way that the digital print cannot.

This is directly related to the obstinacy of the material (its refusal to go along with things). The mason has to negotiate, to coax and entreat both his hands and the material into becoming something. This interaction changes both the mason and the stone into something new. And so it is with the painting on the side of an Attic vase. You can see the light of the day on which it was made, you can hear the chatter in the artisan’s mind and feel the breath held in that moment of silence when the stroke is drawn upward and released. All this is right there in front of you.

1Leonardo da Vinci, in Leonardo on Painting, ed. Martin Kemp (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2001), p. 14.

2Maurice Merleau-Ponty, “Eye and Mind,” in The Merleau-Ponty Aesthetics Reader: Philosophy and Painting, ed. Galen A. Johnson (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1993), p. 126.

3Cennino d’Andrea Cennini, The Craftsman’s Handbook (Il Libro dell’Arte), c. 1400, trans. Daniel V. Thompson, Jr., 1933 (New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 2016), p. 5.

4A reference to Henry David Thoreau, who in 1845 built and lived in a simple cabin on the shore of Walden Pond in Massachusetts, and wrote about his experiences in Walden; or, Life in the Woods (Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1854).

5Étienne Decroux, in The Decroux Sourcebook, ed. Thomas Leabhart and Franc Chamberlain (London and New York: Routledge, 2008), p. 86.

6Ibid., p. 49.

7Donald Judd, “Specific Objects,” in Contemporary Sculpture: Arts Yearbook 8 (New York: The Art Digest, 1965).

8Alain Robbe-Grillet, “Nature, humanisme, tragédie,” 1958, in Pour un nouveau roman (Paris: Gallimard, 1967), p. 83.

9Lygia Clark, “Nostalgia of the Body,” in Rosalind E. Krauss, Yve-Alain Bois, Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, et al., eds., October: The Second Decade, 1986–1996 (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1998), p. 37.

10Isaac Babel, “Guy de Maupassant,” in David Richards, ed., The Penguin Book of Russian Short Stories (London: Penguin Books, 1981), p. 265.

Richard Wright, Gagosian, Davies Street, London, March 29–May 13, 2023