Gwen Allen is professor of art history and director of the School of Art at San Francisco State University. She is the author of Artists’ Magazines: An Alternative Space for Art (MIT Press, 2011) and the editor of The Magazine (Documents of Contemporary Art series, MIT Press and the Whitechapel Gallery, 2016).

When I began working on my PhD in art history in the late 1990s and early 2000s, I used art magazines as a means to an end: like most researchers, I saw them as archives of information and ideas that I mined to further my research, which focused on American art of the 1960s and 1970s. Digital databases and other online resources were still in their infancy at the time, and in order to obtain articles from a magazine, past or present, one had to locate the actual printed periodicals, most of which were preserved in bound volumes. At Stanford, where I was a student, these heavy volumes happened to be in the basement of the art library, and to avoid having to repeatedly lug them up to the photocopier on the second floor, I would often sit on the floor between the stacks and skim multiple sources to be sure of their relevance. As I sat leafing through these old magazines to locate the article or articles I sought, I would inevitably become distracted by other pages—neighboring articles, letters to the editor, even advertisements, an entire context of texts and images that constituted both the physical and the discursive setting within which an article originally lived.

I also began to notice unusual texts, and pages that could not easily be categorized. A number of articles by artists such as Mel Bochner, Dan Graham, Sol LeWitt, and Robert Smithson, for example, seemed to occupy some ambiguous ground in between magazine articles and works of art. They did not fit within the usual run of art criticism, but instead used parody, pastiche, and appropriation in ways that destabilized the reader’s expectations. Even the layouts of these articles were sometimes unusual, stressing their indeterminate status. Other artists took out ads that again did not quite conform to the standard gallery posting. The January 1967 issue of Artforum, for example, included a full-page ad consisting of a photograph of Ed Ruscha asleep in bed, sandwiched between two women; superimposed over the image, supposedly intended as a cheeky wedding announcement on the occasion of his marriage to Danna Knego, was the text “Ed Ruscha Says Goodbye to College Joys.” (Not coincidentally, Ruscha happened to be working as a designer for Artforum at the time, under the pseudonym “Eddie Russia.”)

Other artists followed suit, using art-magazine advertising space as a site of artistic and political intervention. In the twelve consecutive issues of Artforum from November 1968 to December 1969, Stephen Kaltenbach placed a series of ads consisting of pithy and ironic phrases, such as “Art Works,” “Build a Reputation,” and “Become a Legend,” that critiqued the role of the art magazine in careerism and promotion. The artist then known as Judy Gerowitz, her married name, placed a full-page ad in the October 1970 issue of Artforum to announce her name change to Judy Chicago—a decision she explicitly linked to her feminist politics, and her intention, as the ad stated, to “divest herself of all names imposed upon her through male social dominance.”1

Such examples attest to the fact that the magazine page was beginning to function in a new way during this time. No longer merely a place for art criticism and commentary on art, it was becoming an actual site for art—a new kind of medium and exhibition space. This new site became the topic of my dissertation and subsequently of my book Artists’ Magazines: An Alternative Space for Art.2 As my research progressed, my approach to magazines evolved: no longer a means to an end, they became fascinating objects in and of themselves. I started to pay attention to their graphic design and typography as well as to their complex “social lives,” a term I borrowed from Arjun Appadurai to suggest how magazines gain meaning through their production, distribution, and circulation through space and time.3 Many of the publications I discovered were produced by artists as alternative sites of distribution and display that deliberately opposed themselves to more mainstream art magazines such as Artforum.

While these magazines find precedents in earlier avant-garde periodicals associated with movements such as Surrealism, Dadaism, Constructivism, and Futurism, the postwar period witnessed an unprecedented expansion of the formal and conceptual possibilities of the magazine, as well as a self-reflexivity about its status as a medium. This new understanding of the artists’ magazine can be traced back to several periodicals from the late 1950s and early 1960s, including Spirale (Bern, 1953–64), Zero (Düsseldorf, 1958–59), Gorgona (Zagreb, 1961–66), Revue Nul = 0 (Arnhem, 1961–64), Revue Integration (Arnhem, 1965–72), Diagonal Cero (La Plata, Argentina, 1962–68), kwy (Paris, 1958–63), Revue Ou (Paris, 1958–74), material (Darmstadt and Paris, 1958–59), décoll/age (Cologne, 1962–69), V TRE (New York, 1964–79), and Semina (Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Larkspur, California, 1955–64). These publications, many of which had tiny print runs of just a few hundred copies, exemplify a radical new kind of experimentation, as artists utilized unbound, die-cut, and embossed pages, glued objects onto pages, tore them, and even burned them, exploring the temporality and materiality of the printed page. By the late 1960s and ’70s, artists were approaching the magazine as a new kind of artistic medium, exploring the materiality of language and print, as well as the tactility and interactivity of the magazine itself.

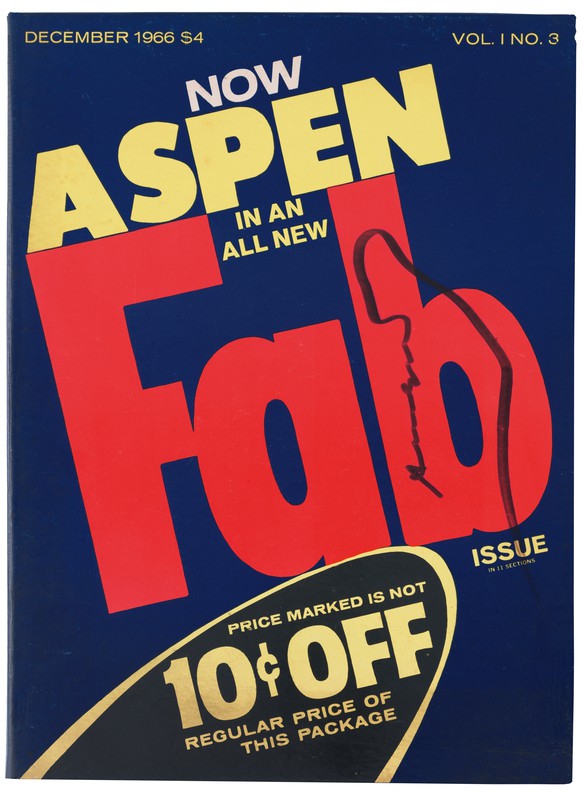

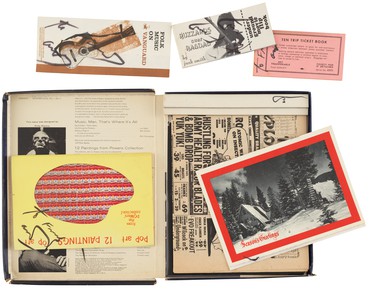

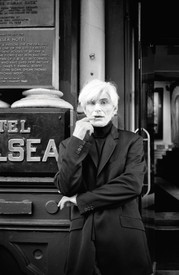

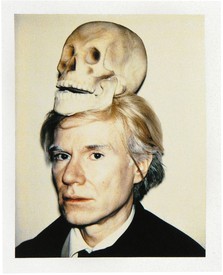

One of the most extraordinary examples of this artistic experimentation was the multimedia publication Aspen (1965–71), which arrived as a cardboard box containing Super-8 films, flexi disc records, critical writings, and artists’ projects. Founded as a culture-and-lifestyle magazine centering on Aspen, Colorado, it was soon taken over by a series of artist guest-editors. Andy Warhol edited issue 3, the cover of which took the form of a box of Fab laundry detergent; inside the box were flip-books, postcards, a mock newspaper, and a flexi disc record of the first Velvet Underground single, “Loop”—7 minutes and 14 seconds of guitar feedback recorded by John Cale. Functioning as a kind of miniature traveling exhibition, Aspen claimed such contributors as Bochner, Graham, LeWitt, Smithson, John Cage, Dennis Oppenheim, Nam June Paik, Yvonne Rainer, Robert Rauschenberg, Ed Ruscha, Richard Serra, and Tony Smith, among others. Artists used the publication to document their work and ideas, but they also saw it as a medium in its own right, taking advantage of its unbound three-dimensional format. Serra, for example, published a handwritten account of an idea for a piece called Lead Shot, which was to involve dropping molten lead from an airplane onto a precise point on the Earth’s surface; Ruscha contributed a poster featuring one of the photographs from his book Thirtyfour Parking Lots (1967); and Smith created a cardboard model of his sculpture The Maze (1967), which the reader could cut out and paste together.

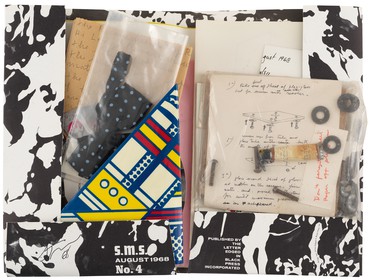

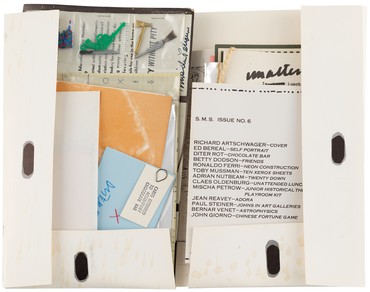

Another important artistic experiment with the magazine form was S.M.S. (1968), a bimonthly portfolio, published in New York, containing intricate limited-edition artists’ objects and multiples. S.M.S. was published by the artist William N. Copley, who invited many artists to contribute, among them Richard Artschwager, Christo, Bruce Conner, Walter De Maria, Marcel Duchamp, On Kawara, Roy Lichtenstein, Lee Lozano, Man Ray, Bruce Nauman, Meret Oppenheim, Claes Oldenburg, Yoko Ono, Mel Ramos, and Lawrence Weiner. Each issue of S.M.S. came in a folder bursting with elaborately designed items: posters, stamps, stickers, toys, games, images and texts reproduced through silk screen and offset lithography, booklets tied with silk ribbons, and tape cassettes nested like jewels in cardboard boxes. Lichtenstein, for example, created a folded hat decorated with his signature Benday dots; De Maria published eight offset lithographs documenting correspondence, sketches, and a photograph describing his proposal for the exhibition Art by Telephone, at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago; Artschwager designed the portfolio cover for issue 6, faithfully reproducing the stains made when he accidentally spilled his coffee while working on it. Man Ray irreverently added a lit cigar to a reproduction of a self-portrait drawing by Leonardo da Vinci in his Father of Mona Lisa (1967)—a kind of rejoinder to L.H.O.O.Q. (1919), in which Duchamp had drawn a mustache and goatee on a postcard reproduction of the Mona Lisa. If magazines presented opportunities for artistic innovation during this period, they also gained meaning as sites of social and political protest. Hence, the title of S.M.S. stood for “Shit Must Stop”—an antiestablishment imperative to halt corruption inside and outside the art world.4

The idea that art could be produced and distributed inexpensively to a wide audience corresponded to the egalitarian ideals that so many artists espoused during these years. In this sense, artists’ magazines and publications functioned as alternative spaces in which to counter the exclusivity of the gallery space and the mainstream art world, and thus radically transform the reception of art. Magazines offered an important new site of distribution and display for the ephemeral and anti-institutional formats and media of Conceptual art, performance art, Earth art, and video, which were challenging to exhibit and commodify. At the same time, they also fostered new artistic communities, audiences, and counterpublics, both locally and globally.

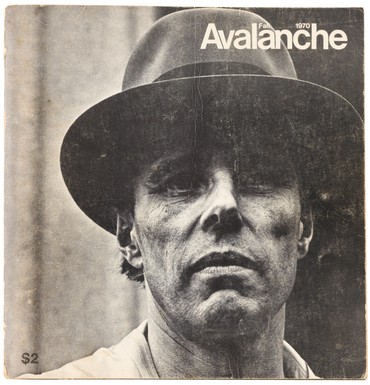

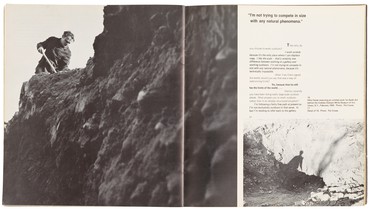

Avalanche magazine (1970–76) was founded by the curator Willoughby Sharp and the writer Liza Béar to support the new forms of art then emerging in SoHo, an industrial section of Lower Manhattan where artists had been illegally living in manufacturing and warehouse spaces since the early 1950s. Styling itself as a hipper, downtown alternative to Artforum, Avalanche sought to put the artist’s voice first, circumventing the critic, and to give artists a place to document their work and to create projects expressly for the page. To this end it published a close-up headshot of an artist on the cover of each issue and eschewed art criticism in favor of lengthy and lavishly illustrated interviews with artists. The first issue, for example, contained a conversation between Smithson, Oppenheim, and Michael Heizer, accompanied by no fewer than thirty-two photographs of these artists’ large-scale Earthworks. Several of the photographs bleed across a spread, lending the magazine a cinematic quality.

Over six years, Avalanche published thirteen issues, featuring interviews and projects by artists such as De Maria, Nauman, Oppenheim, Rainer, Ruscha, Serra, Weiner, Vito Acconci, Carl Andre, Chris Burden, Hanne Darboven, Terry Fox, Tina Girouard, Barry Le Va, Gordon Matta-Clark, Meredith Monk, William Wegman, and Jackie Winsor. Beyond their value as primary art-historical sources, the Avalanche interviews attest to the importance of conversation and sociability in the making and viewing of art in the SoHo of the 1970s. They have an unedited, informal quality, suggesting the importance of community above and beyond the commercial and professional relationships that dominate the art world. Instead of exhibition reviews, Avalanche published a section called “Rumbles,” a home-grown compilation of performances, Happenings, exhibitions, openings, readings, and screenings sent in by artists from around the world. Here one could read about performances and screenings by artists such as Burden and Paik. Gossip and information of a more personal nature were printed in a section called “Messages,” a kind of community newsletter with news of births, deaths, comings and goings, and the like, as well as rumors, such as an anonymous report that Elizabeth Taylor would star in Warhol’s next movie. Before Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, artists kept track of one another and communicated through the pages of magazines such as Avalanche.

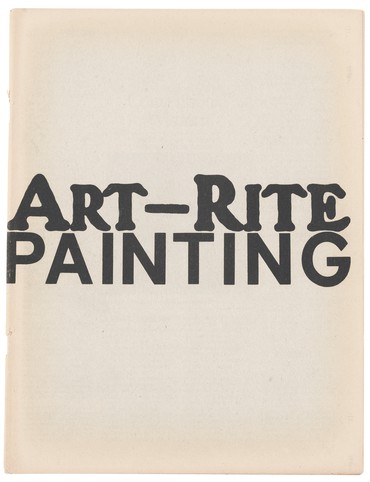

Artists’ magazines challenged the visual culture and conventions of the mainstream art press through not only their content but their form. Art-Rite (1973–78), for example, emerging like Avalanche from downtown New York, rejected the glossy pages of commercial art magazines in favor of cheap newsprint and a diy, zinelike format. It broadcast young and emerging artists and sought to provide a more authentic, accessible form of critical discourse, featuring artists such as Burden, Matta-Clark, and Ruscha as well as younger, less-established artists. The magazine served as a rotating exhibition space through its artist-designed covers, many of them emphasizing and exploiting the publication’s cheap, disposable format. For issue 6, for example, Dorothea Rockburne created one of her “folded drawings” by simply folding back the otherwise blank newsprint cover. The magazine file (1972–89), founded in Toronto by the Canadian collective General Idea, pirated the logo of Life magazine to subvert the dominant messages of the mainstream media with campy and irreverent critiques of class and gender.

These are just a few of the hundreds of artists’ magazines founded during these years as alternatives to the mainstream art press. They also proliferated outside North America, serving as important vehicles of exchange in an increasingly international art world. If they functioned as a kind of alternative art space during the 1960s and 1970s, by the 1980s the very notion of the alternative space was expanding to include venues outside the art world altogether, as artistic communities developed in the context of bands, parties, bars, clubs, and other informal social sites and interactions. A number of important artists’ magazines documented and supported such practices. Real Life (1979–94), for example, founded by Thomas Lawson and Susan Morgan, centered on the New York community of artists known as the Pictures Generation. It published a diverse range of material, including artists’ writings and projects, criticism, and interviews with such artists as Jenny Holzer, Barbara Kruger, Louise Lawler, Sherrie Levine, Richard Prince, and Jeff Wall. Like earlier artists’ magazines, Real Life sought to recalibrate the power balance between artists and critics, offering artists recourse against the critic’s authority. Along with a number of other magazines of these years, such as Just Another Asshole (New York, 1978–87), ZG (London, 1980–88), and Tellus (New York, 1983–93), it fostered interdisciplinary crossovers among the downtown graffiti, poetry, garage band, punk, and no-wave music scenes, represented by artists and musicians such as Kim Gordon and Steven Parrino, both of whom published in these magazines. Other artists explored the publicity role of magazines in ways that both harked back to and departed from the interventions of the 1960s and 1970s, embracing the postmodern blurring of art and commerce. Jeff Koons, for example, turned to art magazines such as Flash Art, Art in America, Artforum, and Arts to take out ads that can be interpreted as both promotional publicity and works of art.

Today, despite (and, perhaps more important, because of) digital culture’s threat to print, artists are returning to magazines and publications as important sites of artistic practice. Artists such as Maurizio Cattelan, Douglas Gordon, Damien Hirst, Josephine Meckseper, Aleksandra Mir, the collective dis, and many others have seized on the magazine format to expand their practice and publics. Yet while artists’ magazines and magazine art today surely have different meanings from those of the 1960s and 1970s, they also rely on this history, whether knowingly or not, and make it newly relevant in the present.

1For a more in-depth discussion of the gender politics of such artist-initiated advertisements, see Gwen Allen, “Making Things Public: Art Magazines, Art Worlds, and the #MeToo Movement,” Portable Gray, no. 1 (September 2018), pp. 5–18.

2The current article draws heavily on that book. See Allen, Artists’ Magazines: An Alternative Space for Art (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2011). For primary documents and texts related to artists’ magazines, see also Allen, The Magazine, Documents of Contemporary Art (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; London: Whitechapel Gallery, 2016).

3Arjun Appadurai, The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986).

4For more on S.M.S., see Allen, “Artist as Publisher: William N. Copley’s S.M.S.,” in William N. Copley, exh. cat. (Milan: Fondazione Prada, 2016), pp. 154–61.

Photos: Rob McKeever