Lars Nittve is an art historian, curator, and writer. For almost thirty years he was the director of a number of major museums around the world, including the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Denmark, Tate Modern, London, Moderna Museet, Stockholm, and most recently M+, Hong Kong. Since the spring of 2016 he has been an independent writer and advisor to museums and foundations worldwide.

The American landscape: we have it in our mind’s eye. Unspecific, but concrete; open and infinite, apart from that mountain range, of course, that always seems to be looming on the horizon. An endless country traversed by telegraph poles, straight roads, and now and then a solitary car—or, actually more likely, a light pickup truck, slowly burrowing its way through the landscape toward the vanishing point. And if it were up to me, that truck would be an early-1950s Chevrolet Advance Design 3100. The 1950s were when the pickup truck boomed, and this Chevy sold more than any other model by far.1 It came to epitomize the hard-working WWII veteran generation and “real American values,” but also, later, the light-hearted American Graffiti teenager. It certainly was everyman’s truck, and maybe that’s why the Chevy 3100, more than any other pickup, has become emblematic in cinema—from small background parts to starring roles, in films from the epic slasher movie The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974) through The Getaway (1972), with Steve McQueen and Ali MacGraw, to Every Which Way but Loose (1978) with Clint Eastwood and Sondra Locke.

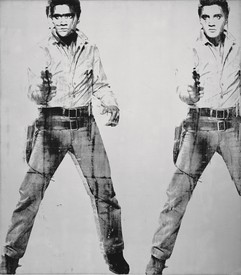

And now, here it stands. Well, not one truck, but three. And not on the concrete apron of a Mobil station along a dusty Route 66, but rather on the polished concrete floor of the bright white industrial cathedral of Dia:Beacon. One black, one dark green, and one equally dark red Chevrolet 3100. No classic beauties, perhaps, but shiny and bright, and with a sort of blunt yet timid charm that, whether despite or because of the absolutely perfect, fetishist finish of every detail, totters on the boundary of the uncanny. The familiar has suddenly turned alien, and we all at once realize that not only are the cars cleaned and polished to perfection, they also appear to have been purged and stripped of any aesthetically superfluous trappings. Gone, for instance, are their side-view mirrors, windshield wipers, license plates, and exhaust pipes. What remains is something exceedingly well-known and comforting—yet foreign. Walter De Maria, the artist behind Truck Trilogy (2011–17), has performed what could be called a classic Marcel Duchamp maneuver, transplanting familiar, mass-produced objects into a museum. More precisely, this would be an example of what Duchamp called the “assisted readymade”—were it not for the fact that more has been subtracted than added.

With the exception of the cargo. On the cargo bed—if you have the opportunity, don’t forget to admire how the Chevrolet designers created a smooth and exquisite metal fold along the edges—there are no chainsaws, or even spades or pitchforks. Instead, three shiny rods of stainless steel rise proudly from the lacquered-wood-panel bed of each truck. One square rod, one triangular, and one round, each exactly eighty inches tall and around five inches thick (their widths vary slightly with their shapes), are grouped in different constellations. The primary geometric shapes of the rods, so incompatible with a truck from the dirt roads but so at home in a museum, are, of course, universal, defined in ancient Greek mathematics and found in most civilizations throughout the ages. The Chevy pickup, on the other hand, is an American icon, rooted in a very particular moment of American history, a moment with which De Maria would have been deeply familiar. Born in California in 1935, he belonged to a generation that learned to drive when the Chevrolet Advance Design dominated rural highways. And it could easily have been a 1950s Chevy pickup truck that drove him into the deserts and mesas of Nevada and New Mexico in search of, and to work on, the major Land art projects that engrossed him for ten years in the 1960s and 1970s, a project that culminated in the extraordinary Lightning Field (1977) in New Mexico.

Three shiny rods of stainless steel rise proudly from the lacquered-wood-panel bed of each truck.

The Truck Trilogy was De Maria’s last work, conceived in 2011 but incomplete when he died, in 2013. Not until now has his estate been able to complete the work in accordance with his early decisions and instructions. The result is singular and unique. And it is striking how, in this and the work preceding it, Bel Air Trilogy (2000–11), and for the first time in a practice spanning more than five decades, De Maria can be said to have transgressed his fixed principle of never leaving his viewers the slightest possibility of confusing his person—his background, his feelings, his life—with his work. As I said earlier, it is impossible to avoid the thought that the 1950s Chevrolets—whether it be the workhorse Advance Design 3100 or the 1955 Bel Air dream ride—coincided with the college student De Maria’s coming of age. It is hard not to imagine that the iconic cars were making a new appearance, after decades of disciplined artistic work, like an American version of Proust’s madeleine, as catalysts of memory. At least for a moment.

But then, of course, there are those ultrashiny stainless-steel rods. They yank us out of our “California Dreaming” and into a world we’ve never set foot in. There they stand on the truck beds, upright, inert, and firmly planted. It is hard to envisage these Chevys speeding down even the straightest of country roads—on the contrary, we sense an echo from the poles of The Lightning Field, which stand immobile, deeply burrowed into the earth. In Bel Air Trilogy, on the other hand—the Bel Air is the car with “a look that’s long, low and lean”2 —a rod, either round, square, or triangular, protrudes through the front and back windscreens with a sort of surgical violence, emphasizing the driver’s perspective, out across the bonnet and arching over the powerful V8.

One set of cars is firmly planted and proud, the other is fast and aggressive—both are simply, strikingly beautiful. With amazingly wide margins, both fulfill the criteria De Maria set for himself in an early interview, namely, that “every work should have at least ten meanings.” They are multifaceted, polysemous, and impossible to pin down or categorize. Yet, the feeling they inspire is intense, dizzying, and hard to handle—the feeling that De Maria strove for and called “the single experience.”3

1See Don Bunn, “Chevrolet Trucks. Segment Five: 1947–1954 Advanced Design Pickups,” online at https://web.archive.org/web/20071018040424/http://www.pickuptruck.com/html/history/chev_segment5.html (accessed March 2018).

2Tony Swan, “A Fabulously ’50s Way to See the USA,” New York Times, October 21, 2011.

3Walter De Maria, quoted in David Bourdon, “Walter De Maria: The Singular Experience,” Art International 12, no. 10 (December 1968), p. 39.

Artwork © 2018 Estate of Walter De Maria; photos: Rob McKeever unless otherwise noted