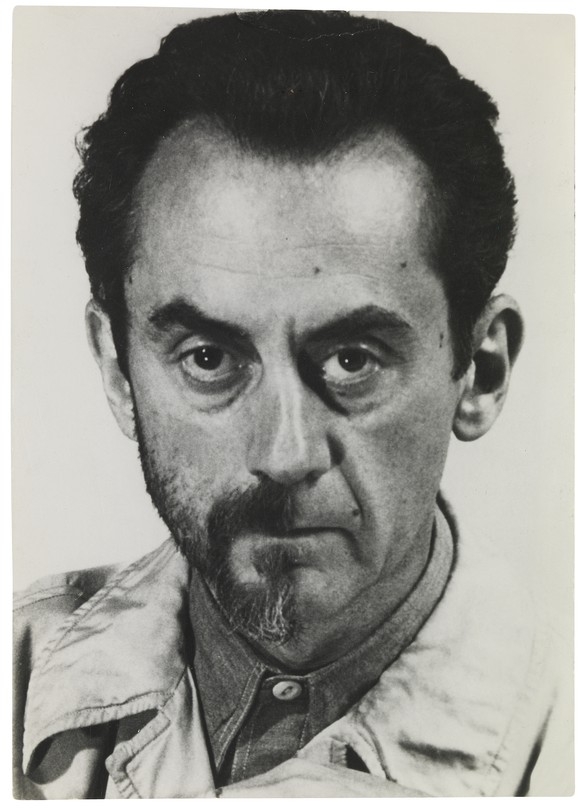

Timothy Baum is a private art dealer and writer, specializing in Dada and Surrealism. He is also the publisher and editor of Nadada Editions, and is separately working on a catalogue raisonné of the paintings of Man Ray, in association with a Paris colleague, Andrew Strauss. He lives and works in New York.

When Man Ray left New York in the summer of 1921, he did so with the resolve of never living there again. The city had in many ways become a monster to him: a compost heap of disappointing memories, interspersed, luckily, with a few artistic successes. Primary among his defeats was the failure of his marriage, to a Belgian who had opened his eyes to the enticements of life in Europe, and especially its conduciveness to the needs and inclinations of an inveterate artist like himself. This dream of Europe—and especially of Paris, its ultimate romantic mecca of culture and sophistication—was enhanced by various alluring visitors from the Continent whom Man Ray had met during his impressionable early years as an artist, not least of them the elegant and inspiring Marcel Duchamp, but other exciting notables as well.

From the moment of Man Ray’s arrival in Paris, he sensed that he was finally in an environment that could nurture him in every way. He was welcomed immediately by a coterie of admiring Dadaists who accepted him with profound respect in the warmest and most cordial manner. He had found his home at last.

From that radiant summer of 1921 all the way through to the dark one of 1940, two decades later, Man Ray thrived in Paris. Life bore him good fortune there—especially the security of being accepted in every social way, including as a member of the artistic elite. Nothing but a dire emergency could have dislodged him from the pleasure and contentment of being an adopted Parisian. Then—shockingly and unpleasantly—that dire emergency appeared. Within a few weeks in May and June of 1940, the German army entered and conquered its neighboring lands of the Netherlands, Luxembourg, and Belgium, then swept into France, arriving in Paris by the end of the second month. The French government surrendered, panic ensued, and a multitude of inhabitants of Paris were forced to flee. The city was now no place for a veteran Dada artist of Jewish descent, and Man Ray, like many of his French and expatriate counterparts, had no choice but to leave in haste. The departure devastated him. Having no preconceived choice for his next destination, he decided to return to America, where he had hoped never to live again. He confusedly headed south, gained an exit permit from France in Biarritz, and eventually reached Lisbon, where he boarded a crowded ocean liner (in the company of, among others, Gala and Salvador Dalí) and made the crossing to New York, the city he had been so happy to put behind him almost twenty years before. Many who had had to flee Europe were enormously grateful to be in New York. Man Ray refused to join that throng; after spending the summer with his sister and her family in New Jersey, he drove cross-country with a traveling salesman he had met and eventually ended up in Los Angeles.

Los Angeles, in 1940, was a cultural oasis compared to Paris and New York. Man Ray knew almost no one there, but with good luck had been given the name of a New York girl who had moved there temporarily, was barely able to make ends meet, couldn’t afford to return home, and was glad to make the acquaintance of a gentlemanly artist from Paris, and one who, like herself, originally came from New York. These transplanted travelers gravitated to one another and very shortly bonded in a beautiful and loving way. The young lady’s name, appropriately enough, was Juliet, and blessedly, unlike her counterpart in Shakespeare’s tragic saga, her relationship with her “Romeo” was not ill-starred—indeed they remained faithfully together for the rest of Man Ray’s life. (And what more suitable setting could we prescribe for the beginning of this nonfictional story of love and devotion than our own inimitable Hollywood USA!).

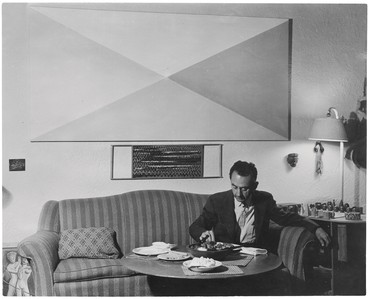

With such a steadfast Juliet as his beloved, Man Ray was able to sustain the ups and downs of life in Los Angeles for almost a decade. He set up a studio and darkroom in their apartment on Vine Street and resumed his dual career as both painter and photographer. By the end of 1941, he had had a small retrospective exhibition in the highly esteemed Frank Perls gallery, but hardly any works sold. Over the course of the decade, other exhibitions followed (including one with Julien Levy’s gallery in New York), but to little financial gain. Luckily Man Ray had a small cushion from money he had earned during his successful tenure as a fashion photographer during his final years in Paris, which helped to sustain him and Juliet through the leaner LA years.

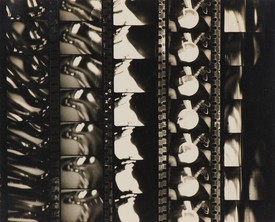

Continuing to work as a photographer throughout his decade of exile in California, Man Ray gradually built up a portfolio of California-related images of some renown. Many Hollywood luminaries sat before his lens, including local or visiting artists and writers as well as an array of actors and actresses and other interesting personalities (the proud Igor Stravinsky, among others). He also explored the splendor of the California habitat: the redwood trees, the beaches, the Pony Express Museum, the movie studios, and more. He did not waste his time, then, during his unexpectedly long stay in California in the 1940s—he was always able to find some form of exploration and adventure. Such was the nature of this endlessly inspired and creative man: always a seeker, and always able to immortalize his findings as well.

Artwork © Man Ray Trust/Artists Rights Society (ARS)/ADAGP, Paris 2018