Robert M. Rubin is an essayist and cultural historian who has written about Pierre Chareau, Jean Prouvé, Alexander Calder, Buckminster Fuller, Reyner Banham, Richard Avedon, Allen Ginsberg, Glenn O’Brien, Jack Kerouac, Jeff Koons, and Richard Prince. He has contributed to Bookforum, Art in America, Cahiers d’Art, Le Monde, and Libération.

HITCH-HIKER: What makes you run?

KOWALSKI: I’m not running, I’m just going.

HITCH-HIKER: [ironical] But you kind of going fast!

KOWALSKI: Speed is a relative thing.

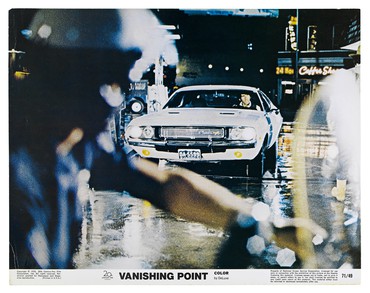

A man in the employ of a Denver garage drives other people’s cars to various cities. He bets his drug dealer that he can make the trip to San Francisco in under fifteen hours, although typically it takes double to triple that if you eat, sleep, and observe speed limits. The stakes: double or nothing on a packet of bennies. Despite being high on speed the entire movie, our hero, played by Barry Newman, is a man of few words. Through a series of flashbacks, we learn he is a decorated Vietnam War vet, a former motorcycle and car racer of some talent, and a dishonorably discharged cop.

Kowalski—we never learn his first name in the film, though in the script we’re told it’s Krzysztof—is pursued by increasingly large contingents of cops across various state lines. He evades them all in a series of thrilling car chases. In so doing, he becomes a celebrity fugitive thanks to the on-air rapping of Super Soul (Cleavon Little), a blind Black DJ. The two men appear to be able to connect telepathically as well.

Kowalski detours into the desert, where he meets a grizzled but helpful snake hunter (Dean Jagger) and a weird, hostile faith-healer named J. Hovah (Severn Darden). He picks up a gay couple hitchhiking (Anthony James and Arthur Malet) who try and fail to rob him. A biker named Angel (Timothy Scott) and his naked girlfriend (Gilda Texter) replenish his supply of bennies and help him get through the next roadblock by fabricating a police siren and lights out of, among other things, a minibike. He picks up a mysterious hitchhiker in black who may represent Death (Charlotte Rampling).

She smokes a joint. He demurs but gets a contact high. They have sex. He falls asleep and wakes up to find her gone. Soon after, he intentionally kills himself at speed rather than surrender. Or, he dies believing against all odds he can pierce the last roadblock, made of two massive bulldozers, and make it to the coast. Take your pick. His only violation of the law has been exceeding the speed limit, if you don’t count popping bennies without a prescription or resisting arrest, but he goes out with a bang. This, in a nutshell, is the story of the 1971 movie Vanishing Point.

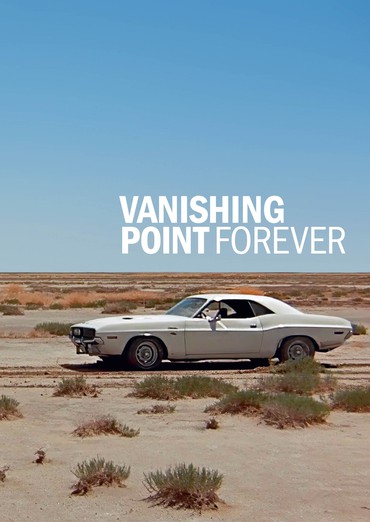

But how do you describe what the movie is, exactly? A goodbye kiss to the ’60s? Along with Two-Lane Blacktop, its döppelganger from the same year, it is the cream of the Easy Rider crop (1969). The ultimate analogue car-chase movie? It’s on everyone’s top-ten list, along with Bullitt (1968), The French Connection (1971), and Dirty Mary Crazy Larry (1974). A hundred minutes of extended Chrysler product-placement? The Dodge Challenger R/T 440—a.k.a. the Kowalski car—is the iconic movie muscle car (R/T stands for “Road/Track”). Dystopian allegory? Vanishing Point anticipates the surveillance-society determinism of films like The Parallax View and The Conversation (both 1974), yet celebrates Kowalski as “the last American Hero,” a modern cowboy trying to outrun the future. With great car chases. Vanishing Point, Nicholas Godfrey writes, is a film “in conflict with itself.”1

What’s a Vanishing Point, Anyway?

First conceived by Renaissance architects, a vanishing point is the point at which receding parallel lines viewed in perspective appear to converge. It has also come to mean the moment when something that has been growing smaller or increasingly faint disappears off the horizon. It’s a cool title for a movie, but Richard Sarafian, the film’s director, likened Kowalski’s trajectory to something more akin to an ellipse or a Möbius strip: a singular surface with no boundaries and no end. At one point in the movie Kowalski realizes he has driven over his own tracks. To escape the Möbius strip you have to make yourself vanish.

But Vanishing Point didn’t vanish. It’s had a rich afterlife. After filling out the bottom half of drive-in double bills with The French Connection and Dirty Mary Crazy Larry for several years, the film rattled around in grindhouse theaters and on television behind the Iron Curtain, along with other New Hollywood films that were snuck in as ostensible critiques of capitalist society. It was shown once on network television, in 1976, and was remade into a very bad TV movie in 1997, with Viggo Mortensen as Kowalski (with a disclosed first name this time: Jimmy).

The original film was restored and revived at Cannes in 2005, along with Two-Lane Blacktop. After decades of below-the-radar status when you had to chase down worn VHS tapes, there is now a two-disc Blu-ray version with lots of extras. For one thing, the package brings back the movie’s enigmatic phantom, Charlotte Rampling, whose excision from the film has been fetishized into the missing link (see, for example, “Missing in Action: The Lost Version of Vanishing Point”).2

Rampling’s seven-minute scene as a mysterious hitchhiker whom Kowalski picks up near the end was cut from the American release of the film and became legendary “lost” footage until found in the British version, which is now part of that deluxe Blu-ray set (Region 2). If you can’t get your hands on or play that and have to make do with the Japanese Blu-ray or the regular old DVD, the cut footage is now viewable on the web. Just pause your DVD at 1:29:42, Google “Charlotte Rampling Vanishing Point,” watch the clip, and then resume the DVD.

A generation after its initial release, the film is routinely appropriated by artists across multiple media. Worshiped by gearheads, French post-structuralists, and hardcore cineastes alike, the movie is mentioned as often in muscle-car magazines as it is in Film Comment or Cahiers du cinéma. It has an equally extensive bibliography, running the gamut of commentators from Alberto Moravia to Quentin Tarantino. As Sarafian summed it up in 2008 on the DVD’s bonus featurette, Built for Speed, “The movie wouldn’t die . . . it’s still not dead.”3 It’s as present as ever.

As for Rampling, she joined Abe Vigoda and Dick Miller in Cutaways (2013), a remarkable bit of metacinema in which the three reprised their deleted characters from Vanishing Point, The Conversation (Vigoda was Harry Caul’s lawyer), and Pulp Fiction (Miller was Monster Joe).

Who Is Guillermo Cain?

Barely mentioned in all the ghost stories is the remarkable screenplay by one Guillermo Cain—the screenwriting nom de plume of Guillermo Cabrera Infante (1929–2005). Indeed, one commentator, the indie director Alex Cox, has gone so far as to suggest that Cabrera Infante didn’t really write it, claiming the screen credit and the paycheck were a payoff for Cabrera Infante’s alleged work for the CIA.4 We can certainly put that theory out of its misery and situate Cabrera Infante in his rightful place in the history of Vanishing Point. Without getting into a whole Orson Welles/Herman Mankiewicz auteur theory discourse, suffice it to say that the film owes its brilliance to the collective, if not always cohesive visions of producer Richard Zanuck, Sarafian, Cabrera Infante, cinematographer John A. Alonzo, and stuntman Carey Loftin (with a little help from vehicle wrangler Max “The Surgeon” Balchowsky).5 Not to mention the cast: Newman, Little, Rampling, and, in his final onscreen role, Jagger. Up until now, Cain, like his biblical forebear, got no respect. But he—not Rampling—is the missing link.

Whole chunks of the final shooting script were jettisoned along the way. Much of what was kept was stripped of its nuance. But what was left of Cabrera Infante’s original vision is what makes the film more than just a Bullitt for the open road, or Dirty Mary Crazy Larry without Mary. (If you want to see what the film might have looked like without the hand of Cain, tape your eyelids open and force yourself to watch the TV remake, which removes everything from the original that was original.)

In the final script, Cabrera Infante was careful to throw in a commercially critical mass of bikers and hippies ingesting drugs and having casual sex. But he also crafted a magical realist road movie around those exploitation motifs, describing, for example, the white of the car as “fatally Melvillean.”6 (The crew would say white was right because it showed up the best against a desert backdrop.) Cain’s script is populated with fantastical characters on the margins of a hollowed-out America, sprinkled with metacinematic references and montage flashbacks intercut with scenes pulled from classic westerns and Keystone comedies, and highlighted by plans for a pioneering soundtrack of ahead-of-their time samplings. Cabrera Infante reached deep into his cinematic trick bag, overflowing with ideas from his formative years as a film critic in Havana (writing under the name G. Caín). A half century later, with everything that’s transpired around and been appropriated from the film, the final shooting script is well worth a close reading, if only to see what its author had in mind before being mugged by Hollywood.

The Car’s the Star

Like Vanishing Point to the ’60s, the Dodge Challenger was late to the pony car party. The term “pony car” derives from the Ford Mustang, which started it all in 1964, and is somewhat interchangeable with the term “muscle car.” In general, muscle cars are bigger, powered-up versions of regular pony cars. The Challenger straddles both categories. It’s a close cousin of the Plymouth Barracuda, an early Chrysler riposte to the Mustang, and is often confused with its sister car, the Dodge Charger. The Charger emerged in 1966 and was sexed up in a 1968 redesign. The Challenger debuted in 1970 and is essentially the same car, offering the same gamut of engine choices, a bit lighter and faster.

Even Quentin Tarantino couldn’t get it straight at first: the early draft screenplay for his vehicular slasher film Death Proof (2007) refers to a Dodge Charger (you can find it on the Internet). He fixed it by the time he shot the film (and it’s corrected in the published screenplay). The premise: a pair of stuntwomen working on a cheerleader film in rural Tennessee find a pristine white Challenger identical to Kowalski’s for sale to “test drive.”

If you want a Kowalski Challenger, here is precisely what you need in the way of a 1970 Dodge Challenger R/T:

– 440 CID V8 “U” code

– 4bbl carburetor

– 4-Speed manual transmission

– “A-833”4.10:1 Sure-Grip differential

– Pistol grip shifter

– Alpine white exterior

– Black vinyl interior

– Bucket seats

– Heavy-duty shocks

– Rallye wheels

In other words, not a Hemi and not a “six pack,” the maximum engine and carburetor setups available for the Challenger. And despite Super Soul’s reference to the car being supercharged, the Kowalski cars were not. According to Sarafian, the bulk of the film’s cost overruns were to pay sound engineers to enhance the car noise in postproduction and “give the car the personality I couldn’t.”7

They all weren’t white to start, either. If you look closely, you can see colors coming through white overpaint as the cars were progressively banged up during production.

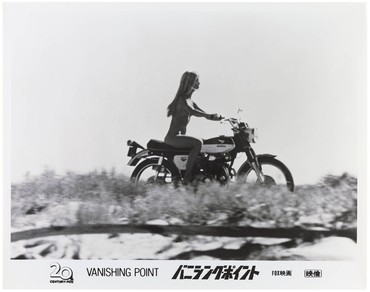

Girl Next Door on a Motorcycle

Cabrera Infante would undoubtedly have seen Girl on a Motorcycle, as it was one of the top UK box office hits of 1968. In the writer’s freely associative mind, removing Marianne Faithfull’s leather jumpsuit was not a big leap.

The image of a naked hippie chick on a motorcycle became the iconic representation of the film, at least as far as the European marketing department was concerned. (In a classic bait and switch, the campaigns also featured Charlotte Rampling even though she had been cut from the movie.) The image appears in a recurring disc shape in the Italian Fotobusta poster series, and also as the centerfold of Carole, the French film-fan magazine. The trope of the naked girl on a motorcycle (which dates back to Lady Godiva, astride the precursor of the internal combustion engine) entered the pop-cultural mainstream via Vanishing Point.

Richard Prince’s obsession with muscle cars in general and Kowalski in particular is well-known, but there is another link between his work and Vanishing Point hiding in plain sight: the girl on the motorcycle is the foremother of Prince’s Girlfriends series.

The important thing here is she looks like the girl next door. (Before Easyriders magazine, naked girls on motorcycles were limited to porn and fetish mags.) No sexy lingerie for our Gilda, who wasn’t even an actress/model/whatever when she showed up on set in 1970 (her IMDb page indicates she would go on to have a long, successful career as a Hollywood costume designer). She sports a healthy all-over tan, blond hair, blue eyes, and a smile full of sunshine. Driving around aimlessly, she’s part of the scenery until summoned by Angel to verify Super Soul’s voice on the radio, then left for Kowalski to have his way with (which he politely declines). In any event, the sex on offer is casual, innocent. Lust is not in the air. She is merely the perfect hippie hostess.

Texter was the girlfriend of actor Paul Koslo, who played one of the cops. Sarafian conscripted her for the part. You could say that she was offered up, just like in the movie. They didn’t even give her character a name (she’s Nude Rider in the credits). But on the strength of her drive-by, she would go on to act in the biker film Angels Hard as They Come (1971) and would follow that up with another minor exploitation film, Runaway, Runaway (1971). By 1972, her career as an actress had ended as abruptly as it began.

In June 1971, the inaugural issue of Easyriders magazine appeared—a major step in the mainstreaming of the biker cult on the heels of the film whose name the magazine appropriated (or rather reappropriated—Dennis Hopper took it from an old blues lyric). Initially the magazine ran posed, risqué photos of chicks on bikes. Maybe they weren’t Playboy-bunny-grade beautiful but they met a certain standard of attractiveness. By the end of the decade, the magazine had inaugurated the practice of having readers send in photographs of their bikes adorned by their actual girlfriends in various states of undress. Known as the “Ol’ Ladies in Action Photo Contest,” it offered the winners modest cash prizes but, more important, exposure—as much for the bike as for the girlfriend. Prince recently described them to me as “the real girl next door.” Over time, crotches would be shorn of pubic hair, and the magazine’s awkwardly posed, sent-in biker girls would yield the pages back to pro models in slicker, shinier, two-wheeled tableaux vivants. The pro models on bikes were now being art-directed into idealized versions of the sent-in pix of the original girls next door.

Gilda Texter is Girlfriend Zero.

1Nicholas Godfrey, The Limits of Auteurism (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2018), p. 102.

2Wheeler Winston Dixon, “Missing in Action: The Lost Version of Vanishing Point,” in Dark Humor in Films of the 1960s (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015).

3Richard Sarafian, director’s commentary, Vanishing Point, special ed. Blu-ray (Los Angeles: Fox Home Entertainment), 2009.

4Alex Cox cites as evidence the fact that Guillermo Cain’s native language was not even English—though that didn’t prevent the author from translating James Joyce’s Dubliners (1914) into Spanish. Cox, “Vanishing Point,” AlexCox.com, August 11, 2015. Available online at https://alexcoxfilms.wordpress.com/2015/08/11/vanishing-point/ (accessed December 12, 2023).

5See, for instance, Godfrey’s Limits of Auteurism for one of the better commentaries on the film.

6Final shooting script, p. 7, shot 67.

7Sarafian, director’s commentary, Vanishing Point special ed. Blu-ray.

The “Gagosian & Film” supplement also includes: “Adaptability,” “Whit Stillman,” “Sofia Coppola: Archive,” “On Frederick Wiseman”, and “You Don’t Buy Poetry at the Airport: John Klacsmann and Raymond Foye”

Robert M. Rubin, Vanishing Point Forever (RideWithBob/Film Desk Books, 2024)