Andrew Russeth is an art critic based in New York.

When Jamian Juliano-Villani crashed onto the scene in the early 2010s, a huge amount of wan abstract painting was hanging in galleries that claimed to be devoted to vanguard contemporary art. Her action-packed and crisply precise canvases heralded a long-overdue shift, the start of something new. These early works, made with both an airbrush machine and brushes, are frenetic, overflowing with imagery from deep-cut comics, art history, and elsewhere. Some are vaguely menacing and threaten to spiral out of control.

The key painting from this period, for me, is an unusually restrained one. It takes the red, white, and blue logo of the New York Rangers and slices off the hockey team’s first and last letters to make “ANGER.” It’s a tribute to the late filmmaker Kenneth Anger, but it is also a logo, an escutcheon, for Juliano-Villani. This has to be put carefully, because the result is never malevolent, or even mean-spirited, but: a quiet, simmering anger runs through her practice. Anger fuels it.

Too many artists and curators and galleries play it safe and repeat themselves, rehashing the same tired tropes, as we all know. Juliano-Villani actually does something about it. Her entire career has been a sustained attack on that state of affairs, pillorying the navel-gazing pretensions of the art world along the way. Like Martin Kippenberger, she takes the sensible view that artists (good artists, at least) can and should always be doing more, always pushing. “Simply to hang a painting on the wall and say that it’s art is dreadful,” that German said in an interview with the artist Jutta Koether in the early 1990s.

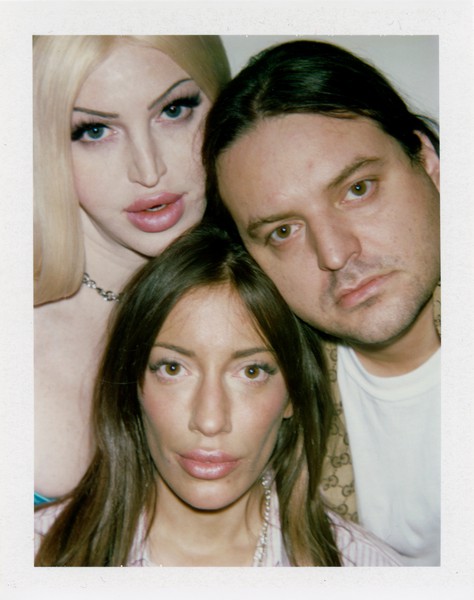

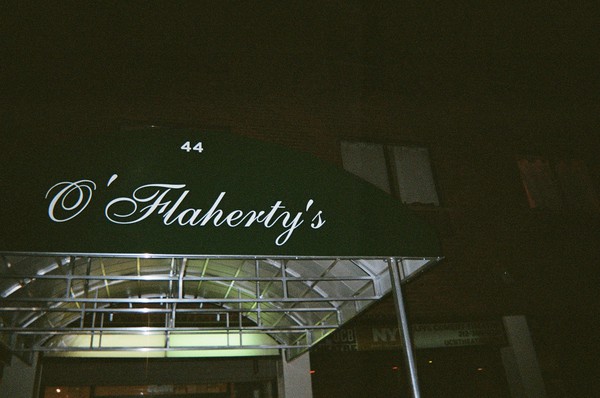

Kippenberger invested in a Los Angeles Italian restaurant and bought a gas station in Salvador, Brazil. Juliano-Villani’s manifold activities have included starting a scrappy gallery in 2021 in Manhattan’s East Village called O’Flaherty’s with artist Billy Grant and musician Ruby Zarsky. The three agreed to do pretty much anything but show their friends. Great artists like Kim Dingle, Ashley Bickerton, Anthea Hamilton, and Christian Ludwig Attersee have exhibited there.

The first iteration of O’Flaherty’s went out with a bang the summer after it opened, with an open-call exhibition, The Patriot, that received more than eight hundred submissions. The gallerists packed them into the space to create “a truly democratic show where everyone is treated equally like shit,” as they put it in their press statement.

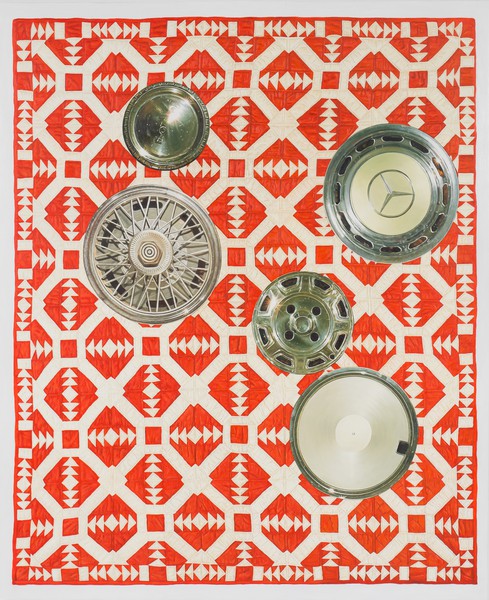

A democratic spirit also radiates from Juliano-Villani’s art. It brushes aside hierarchies of taste, and cribs and repurposes album covers, cartoons, printed matter, and the odd plastic toy. Importantly, though, while the works are built from pop culture, they are not populist. They refuse to pander, to deliver the easy one-liner or the manipulative pitch. Juliano-Villani makes pictures that are as seductive and punchy as television ads, but generally toward opaque, mysterious ends. Viewers have to sift for meaning.

In Chef Mike (2020), Juliano-Villani copies Norman Rockwell’s Thanksgiving-feast masterpiece Freedom from Want (1942), replacing the turkey with an operational microwave. It’s a groan-inducing gag about the USA—until the appliance’s door pops open, revealing disco lights and blasting Edward Maya and Vika Jigulina’s sultry 2009 club classic “Stereo Love”: a characteristically bizarre mixture of kitsch, sex, and earnestness for Juliano-Villani. Standing in front of this thing, even seeing it in videos, you sort of cannot believe it actually exists.

A quicksilver logic reframes highly specific sources in Juliano-Villani’s art. Her notebooks contain entries like “high chair in a cornfield illuminated by cop lights” and “toothpaste on a tennis court,” and her image-filled filing cabinets contain everything from record covers by the Jamaican artist Wilfred Limonious, to outrageous drawings by US animator and filmmaker Ralph Bakshi, to promotional materials for Robbi, the artist’s family’s commercial printing business in New Jersey (probably a foundational influence).

Juliano-Villani has compared some of her paintings to fan art and fan fiction, genres driven by an obsessive love for a cultural touchstone, the desire to imagine and realize more than what exists in a canon. Though she has been known to say that she would never hang her own work in her house, you can tell by the care with which she works that she has a love—or at least a begrudging admiration—for what she chooses to paint. Disgust and respect are intertwined, she reminds us.

If you would like her to portray more pleasing subjects, we would need to live in another time. The artist Mike Kelley argued in a 2008 conversation with Glenn O’Brien in Interview that “copyright laws are terrible for culture. It’s illegal to respond to the imagery that surrounds you; you’re bombarded every minute of the day with mass-media sludge. It should be the opposite: Everybody should have to respond to it.” This is exactly what Juliano-Villani is up to.

The simplistic understanding of Juliano-Villani has long been that she is an artist who makes wily mash-ups of found material, painting with a projector. She does that, with playful equanimity, but her pictures also carry personal resonances and psychological charges. People are in pain and under pressure; they are trying to keep it together. A swimmer is forced to breathe through a plastic recorder in The Sirens (2016), and the artist herself, as a cat, sprawls out next to bottles of Proactiv skin-care products in Self-Portrait in Greece (2017). The cover for a book on napkin folding that she commandeered into a gargantuan painting in 2022 is pure pathos: a volume that could only be owned by someone desperate to impress, who just wants to exude some class while entertaining the boss at home. Napkin art exists for a moment, then it is destroyed.

There is a subtle but piquant uncanniness to her creations, as disparate images and situations, perhaps half-recognized by the viewer, pile up.

Something similar is true of contemporary art. It can lose its potency fast, as images of it circulate. But Juliano-Villani’s recent paintings have an intense speed to them, as if they are aiming to outrun or sidestep that process. They are singular, and strange, and deadpan, almost artless. They are “means to an end,” she told me. The cocksure Bolero Boys (2022) suck identical pacifiers. In Little Girls Stretching (2020), two budding gymnasts who could be twins stare you down with a hint of annoyance. In a new picture, the artist grabs Elvis’s crotch. Oddly, they are wearing matching outfits.

A tangential but essential aside: doubling recurs throughout Juliano-Villani’s art, within and across pictures. It is worth recalling that Sigmund Freud identified the double as one of the markers of the uncanny, which he defined in his 1919 essay “The Uncanny” as “that class of the terrifying which leads us back to something long known to us, once very familiar.” There is a subtle but piquant uncanniness to her creations, as disparate images and situations, perhaps half-recognized by the viewer, pile up.

To conceive of subjects for her paintings, the artist has pursued strategies from various creative realms. She hired a comedy writer to draft scenarios, but found that they were less than promising. Late one night, she convinced bar patrons to fill out Mad Libs for that same purpose, with the same outcome.

Showing her work alongside Kelley’s at a decommissioned ranch out on the East End of New York’s Long Island in the summer of 2022, Juliano-Villani staged a brutally difficult Easter egg hunt with a glorious reward. The person who found a particularly well-hidden egg was entitled to a painting she’d made depicting a horde of people rushing onto the Hampton Jitney bus (or descending into Hell?). It was a little bit evil, a little bit grotesque, to invite people to compete for a potentially six-figure picture, and the ending was too perfect: an eight-year-old nabbed the prize, trampling into an area inhabited by what the artist termed “fucking aggressive bugs.” He said he would sell the picture and use some of the cash go to space camp.

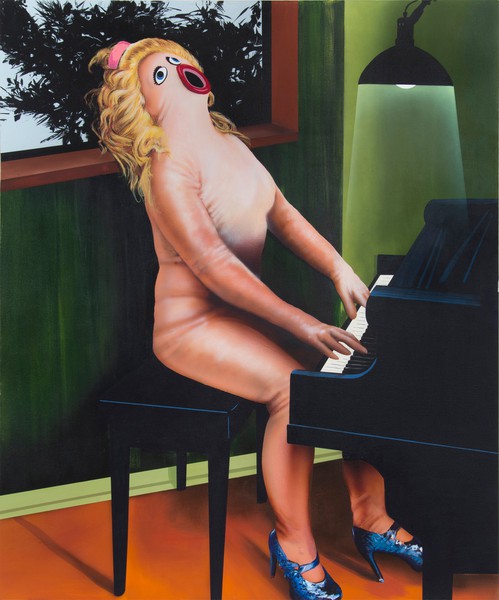

Juliano-Villani’s list of professions is long: gallerist, restaurateur (a O’Flaherty’s one-off), choreographer (she was a cheerleading captain in high school), sculptor, curator, and of course painter. She is a clown, a cat basking in the Mediterranean sun. She is, most of all, an entertainer of a type that recalls a distant era, aware of the risks and responsibilities entailed in putting yourself on display, doing something relevant, facing ridicule.

Juliano-Villani has made a painting called The Entertainer (2015), as it happens. I cannot say it is her best picture, but it is my favorite, and it is lodged in my head. It shows a life-size female sex doll, nude except for sparkling blue heels, sitting at a piano. She might be in a small bar or cabaret (or maybe just her apartment), fingering the keys, singing with gusto. From the light in the room, it appears to be getting late. Does she look familiar from somewhere? Should we be watching? Hard to say. But the fact of the matter is that we are here. She knows what we want, and she will be here well into the night. It looks like she’s just getting going.

Jamian Juliano-Villani: It, Gagosian, 541 West 24th Street, New York, March 16–April 20, 2024

Artwork © Jamian Juliano-Villani