Richard Calvocoressi is a scholar and art historian. He has served as a curator at the Tate, London, director of the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, and director of the Henry Moore Foundation. He joined Gagosian in 2015. Calvocoressi’s Georg Baselitz was published by Thames and Hudson in May 2021.

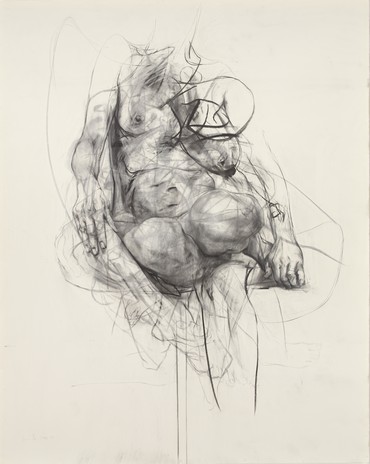

The principle of natural growth is fundamental to Jenny Saville’s art. Nowhere is this more evident than in her drawings, where a mark or line can appear to lead intuitively to another in a fluid process that suggests a growing organism. The forms that develop in this way seem dynamic and self-creative, emphasized by the memory traces they leave on the paper—selected by the artist because of its resistance to erasure. Some of her new, horizontal drawings of coupling nudes have an alloverness that at times undermines their focal point, usually the place of sexual contact. She cites the open-ended, “unfinished” look of one of Leonardo’s tiny sketches for The Virgin and Child with St Anne and the Infant at the British Museum, London, as an inspiration. When describing her drawings, Saville states that:

I wanted the eye to unconsciously slip from one form to another. I’ve been trying to find ways to stretch a feeling of time by layering realities. After working on an image for a while, building up different poses, bodies or limbs start to intertwine and unexpected forms emerge.

It is no accident that in the last few years Saville has become preoccupied with the theme of reproduction and motherhood. She had herself photographed giving birth, “the movement from one body into two.” Pregnancy made her look at her own body again:

I kept thinking of the formation of flesh and limbs inside my body, of regeneration. . . . My multiple drawings—one on top of another—are a way of communicating those feelings. You’re literally reproducing yourself when you’re pregnant, like the way the lines reproduce themselves.

In the atmospheric new drawings exhibited at Gagosian Davies Street this spring, Saville demonstrates a concern with tone rather than line, informed by her close study of Venetian drawings in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. Softer mediums such as pastel and charcoal predominate. Effects of what she calls “slatted light” are achieved by hoovering the pastel: “It gets shifted like paint.” The shifting shapes of Willem de Kooning’s great Woman series come to mind. It is not surprising to find that Saville rates de Kooning highly, especially the small pastels that preceded his large oils: “I don’t know any other painter who could paint flesh without literally painting the body like de Kooning did. . . . The struggle to find form and space. . . that visual wrestling.” In these exhilaratingly free drawings, Saville takes ambiguity to new heights.

When I’ve drawn a body or couple, if I then start to draw and layer other bodies on top, there’s a moment when your perception starts shifting and is in the balance between the two moments or sets of forms. Your eye yearns for wholeness and recognition of form. As I’m working, the previous bodies I’ve drawn visually collapse as they become buried, and the new bodies emerge as the dominant forms. I’m trying to see if it’s possible to hold that tipping moment of perception or have several moments coexist. As your eye moves around the drawing, you tune in and out of different realities or passages of time. Like looking at a memory.

If I draw through previous bodily forms in an arbitrary or contradictory way, unexpected forms emerge from the nature of the drawing and it gives a visual shock. I find it exciting creatively as it gives the work a kind of life force or eros. Destruction, regeneration, a cyclic rhythm of emerging forms—there’s a closer relationship with nature in this way of working that excites me, and it’s particular to drawing.

Writing about the image of woman in Saville’s nudes, Maria Becker suggests that “The feeling they leave the viewer with is borne of an understanding of what it means to be a body.” This ability to get inside her subjects is one of Saville’s strengths. Her new life-size drawings of intertwined bodies, with their erotic undertones, have a sculptural quality. Body forms coalesce and dissolve, as the eye wanders across the surface of the paper or canvas, in the same way that they do when we move around a multi-figure sculpture. Time becomes an important element in the composition. Saville says that she thinks a lot “about how film and music fold out in time compared to drawing or painting—how sensations in these mediums are developed through sequences.” The new drawings are an accumulation of the sensations experienced in making love—the fluctuations and changing dynamics, moments of ecstasy as well as of tenderness and composure.

Artwork © Jenny Saville. Photos by Ashmolean Museum Photo Studio