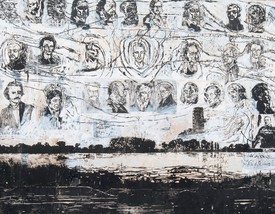

Recent photographs by Andreas Gursky, accompanied by an electronic sound installation by Richie Hawtin—a leading exponent of minimal techno since the mid-1990s—are on view at Gagosian West 21st Street. The photographs include large-format images of politics, painters, nature, and consumer products. Inspired by American postwar painters, such as Barnett Newman, Robert Rauschenberg, Ellsworth Kelly, and Mark Rothko, Gursky’s recent works, most of which have never before been seen in the US, slip between the recognizable and the abstract. Through scale distortions and rhythmic repetitions of motifs, including tulips, solar panels, and mass products, Gursky explores the formal questions of abstraction with the almost musical approach, echoed in Hawtin’s hypnotic soundscape.

In the following conversation, Andreas Gursky and Richie Hawtin discuss their collaboration with art historian Laura Käding.

LAURA KÄDINGHow was the decision made to integrate music into the exhibition Nicht Abstrakt at K20 Museum of the North Rhine–Westphalia Collection in Düsseldorf?

ANDREAS GURSKYI thought about it for a long time. If I remember correctly, we were playing electronic music during the installation of my last Gagosian exhibition in New York, and I started thinking that it would be interesting to have music accompany the show. After that, we carefully considered it, which took quite a bit of time. The music in this exhibition, though, is neither merely accompanying the images nor is it a typical Richie Hawtin sound. Rather, it is a soundscape, which was composed especially for the exhibition and permeates the images in the most peculiar way.

LKIn the exhibition, there are strong similarities between the music and the photographic works: there are sequences, repetitions, frequencies, etc.

RICHIE HAWTIN When I started, I only knew part of the process of how Andreas was working and manipulating the images—but they are manipulated so well that you can’t see any trace of process, and the final image feels real. The longer I looked at the works, the more I was brought in, and the more similarities I found with my own work. So as I was composing, I was changing the instruments and sequences, trying to find something that evolved cohesively, until my eyes and my ears were both kind of hypnotized.

AGSo, you began from scratch and allowed the pictures to affect you? I assumed that you started from earlier sound pieces, which were perhaps dematerialized, but you are saying that’s actually not true. You more or less captured what you saw?

RHIn the beginning, we had discussed the concept and how some of my old tracks were inspiring to you, so I actually started there and tried to deconstruct them, but it didn’t work. I didn’t have enough flexibility. Instead, I took a different approach and started with nothing.

AGBut there were some specific moments that I recognized from earlier pieces.

RHIn your photographs, the location or the landscape exists, but it is how you capture that and manipulate it, your very specific perspective, that transforms it into a work of art. From my side, in a way, the sounds exist, the synthesizers are there, and I understand which ones and which combinations work for me. There is always a texture and a sound within. So when you say that you hear something familiar, it’s not actually a concrete sample from an old work, it’s because I use a similar, limited set of equipment. As a result, there’s a certain texture that rises to the top. And my sequencing is, I would think, like your editing process. There’s only so many notes that exist for you to hear, but it’s which one goes first, or how long and how much space is in between the sounds, that defines it and makes it sound like me.

Once I knew I couldn’t use a loop or a sample from any old work, the first decision was about which of my devices would give me the right atmosphere and sound characteristics. Visual art has always interested me: its different frequencies, its visual frequencies or sonic frequencies. So I was trying to find a point where our works come together without fighting each other, where they would just oscillate at the same level.

AG In other words, the material already exists, what you create is the combination—you put the components into rhythm with each other, which is very related to my process as well. I follow a similar convention of composition in my latest works such as Amazon (2016), Les Mées (2016), or the fields of tulips, which depict vast landscapes, or Amazon, which is a distribution center that includes some 15 million objects. When observed with a natural view, the details on the horizon became indistinguishable, whereas objects in the front are in focus. The viewer is drawn into the space, while the foreground and background are drifting apart. Now, my manipulation of the image seeks to adjust the proportions and scale of the tiny pixels in the back and the objects of the foreground. Figuratively speaking, what I create is a world without hierarchy, in which all the pictorial elements are as important as each other. The experience of space dissolves in favor of a dissected plane that is gradually scanned and read in its linear structure. I see an essential analogy in this structural approach, where my repetitive pictorial patterns and your minimalistic structures of sound overlap.

My photographs are “not abstract.” Ultimately they are always identifiable. Photography in general simply cannot disengage from the object.

Andreas Gursky

LKWhen you compose music, is it ever a visual process for you?

RHUsually the visuals come later, once the music is done. When you are creating an album cover, you are trying to interpret the music in a visual way, to give somebody a connection to the music they haven’t yet heard. That has always been important. If someone came into a record store or was at a friend’s house, you want them to see an album cover and feel a connection. And of course once they hear the music, it needs to feel cohesive. But until now, for me, the visuals have always come after making the music. That being said, it has always been really inspiring to see works by artists like Mark Rothko, Dan Flavin, or Donald Judd, which visually have space and depth, and which have allowed me to imagine them in sound. The space within their works, just how much space and sometimes how little content, can really inspire me to find even more space in my own work back in the studio. Typically, when I’m working, I’ll start with nothing and then add and add and add and add, until I get to a point where maybe I have five layers, each layer informing the next, and then I can take three of them away and it suddenly opens up. Visual art really helped me find that process, because it was physical. Visual art has allowed me to look at something and say, okay, I see the space, so how do I get that space into my music? How do I carve it out?

AGThe American Abstract Expressionists fascinate me. The distinction between photography and painting is still that the viewer always reads photography as what is presented, whereas painting is about the presentation as such. That has always been a guidepost for me. It is interesting to me that someone looking at my work tends to be stunned initially by being first confronted with visual phenomena that cannot be immediately classified. Obviously the social dimension is also enormously important for me, so I will never give up the connection to reality or to society, but it’s not as much of a priority anymore.

LKThe music that accompanies the pictures is like a soundscape, it does not illustrate or narrate, it just lingers in the background.

AGYes, it feels as if something is breathing, something is buzzing. In many ways these pictures, and perhaps all my pictures, present a condition of the world, a constitution of the world. In the exhibition, no linear direction is apparent, nothing takes you from one target to another, it is an observation of the state of being of the world, basically a still life of the world, whether it is an image of flowers or the ocean—and having sound included in this is very supportive for the connection.

Back to your original question about why the sound is included in the exhibition first of all: one has a vast area to fill, and I deliver only at works, pictures on the wall, so the entire area remains unused. I find it obvious in a way, that by including sound, people feel invited to look at the pictures for a little longer. If you observe viewers in a museum, they usually look at a picture for a short time and move on. But with this symbiosis between sound and picture, people may linger more.

RHAll your works, they’re all breathing somehow. Of course they are fixed, but with the sound atmosphere, they have a presence and a life. That adds a nice complement to the photographic works, yet it doesn’t try to change the context. It just brings the senses together. And hopefully, we can create a space where two minutes have suddenly passed, and you realize you’ve just been drawn in, and you can’t actually separate the visual and the sound. They work together to deepen the experience.

AGSince we began our collaboration, I have started paying closer attention to sounds in my daily life. I find that our world is very strongly influenced by images, yet sounds are completely undervalued or ignored. And for me, it is fascinating to develop such a precise sensibility. Certainly, it is different in your case, since you work with sound, you must hear things completely differently than I do. But for the first time, I am recognizing that I have gotten accustomed to sound in certain situations, and now I notice when sound is not there.

RHWe both started our careers in an analog world and now work with digital technologies, and we both continuously look for ways to further develop our craft, our creativity, and challenge the work we have done so far. So, it makes sense that we’re both interested in widening the experience of the listener, of the viewer. But we both have one sense that is magnified—your eyes are more magnified, and my ears are more magnified. Still, we’re very aware of the world. And together, we can bring more senses into an experience, even if only in a very small way. If it is done cohesively, then people are taking all that in, and we are giving them an opportunity for another level of experience. That doesn’t mean that, just because you add sound to a visual experience, it’s going to work. But with the right sensibility, it can come together quite well.

AGTo which extent are you influenced by people like John Cage, Terry Riley, Steve Reich, and Philip Glass? They have all worked with repetition, even to the point where it becomes very monotonous.

RH The type of music that I like, that I try to make, and why I like loops and repetition—it has a beginning and an end, of course, but it’s not a strict narrative. It’s emotional. I hope to create a state of being by using repetition. I want the listener to lose his or her state of being, to stop thinking and feeling, to become locked into a moment. I like to disappear as the producer and allow people to fully let go. But listeners have to want to let go and not to be told something. I want changes to happen without anybody actually hearing the changes, and have those shifts pull the listener in, to an even deeper level. It is hypnosis and momentum that make the experience very organic. So I don’t typically have abrupt changes; I want people to get lost in the sound and the space that is contained within the music.

AGFor me, there is also a parallel on a content level. When I take a picture, the individual object is often trivial, it is merely a detail. But through repetition of hundreds of interiors—in the work Montparnasse (1993)—which show their sameness, or even differences between each other, that is where the picture is created, and that makes it interesting; that is where it can state something more meaningful about existence. And I find it interesting, that it is possible to adhere to that level in music.

RH Techno music began in a club context, which is important because these were quite often very long events. The best DJs were able to blend music together seamlessly—you didn’t know if you were here or there, or how you got from one point to another. You kind of disappear, and it’s just the music surrounding you. And for me, that state is freedom, letting the reality of the world fade away. It becomes just about the frequencies and the space between those frequencies. It’s like sonic escapism.

AGSome of your music is twenty years old, but it’s timeless in a certain way. Perhaps you might want to change or improve those tracks now, but after all, good music should feel timeless.

RHIf you have music with depth and space, then each time you come back and listen to it, one year later or ten years later, you’re going to find something new. You’re going to take a different path. You’re going to listen to it differently. I want there to be enough space for each person to have a unique experience.

AG What was your initial reaction when I asked you to collaborate? Did you have to think it over, or was it immediately clear to you that you wanted to accept the invitation?

RH It was surprising to be asked and wonderful to have the opportunity. But it was also a challenge. Electronic music allows me to create the whole sonic experience by myself. Working on a collaboration takes me out of my comfort zone and makes me think in different ways. I’m not as interested in collaborating with other musicians, because I prefer to make my own thing, but it was very interesting for me to participate with a visual artist. And as an admirer of your work, I knew it would be an entirely new experience.

AG On the contrary, if you were to ask me to compose a picture in response to your work, that would be very difficult for me. Perhaps it is difficult in my case, because as a photographer, I am always dependent on observations; I cannot force a picture.

RH I also never wanted making music to be a job. I wanted it to only happen when I felt there was a reason to do something, either an emotional or a technical reason, a challenge. So, when you asked me to do this project with you, I felt there was a shared belief in unlocking creativity through technical innovation, both from the visual side and from the audio side.

LK Why did you decide that the speakers should not be visible in the exhibition?

RH Well, the installation had to be sonically correct, but also visually correct. There’s already a visual element, so I didn’t want to add anything else that would distract people visually. But people are actually not used to hearing sound without seeing it; there can be very strong correlations to headphones or speakers. So as soon as we took the speakers out of sight, it allowed the sound to have more freedom. Even if someone went to the exhibition, didn’t consciously notice the sound, and left, it would still have had an impact. It still changes the experience. I was very conscious that you only need a little bit of sound to change everything. Reducing sound to a very subtle level often has more power in the end than doing the opposite. Plus, by including speakers, you would have separated the visuals and the sound.

AG Yeah. Of course, you would have had music and you would have had pictures.

RH Exactly. That was the delicate balance we had to find, where the sound complements the visual artworks. The images you chose for the show are vast, abstracted, and mysterious, and the sound installation picks that up and deepens that impression, resulting in a new type of immersive experience.

Artwork © 2017 Andreas Gursky/Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn