Michael GovanI’m very pleased to be speaking with Chris Burden. He lives here in Los Angeles. He’s internationally renowned. His work is in collections across the nation and across the world, including our own. He is also the author of the absolutely spectacular work of art, Urban Light, which is now the new image for LACMA [Los Angeles County Museum of Art]. It has always been my dream to have a museum whose logo or image is actually an artwork and not just a building. That’s a very nice thing to say but also a very hard thing to accomplish. And I think Chris has accomplished that for us. This work of art has been captivating for all of us who visit LACMA and, I think, for the city of Los Angeles as a whole.

Chris Burden is not just known as a sculptor; in the ’70s in particular, when I was going to art school, he was known as one of the most fantastic performance artists. He really changed the genre. Everybody may know of him being shot with a gun in Shoot (1971) and locking himself in his locker as his final graduate thesis project at Irvine. There was much debate over whether he would graduate or not. It was a radical and amazing project.

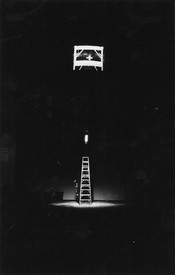

And he’s worked quite often in museums. I have many favorite images of his works that not only were in museums, but of museums. There was a piece that was done at the Henry Art Gallery [University of Washington, Seattle] where there was a 100-ton jack and these timbers pressing against steel plates against the walls of the museum. In the back there was a turnstile, and each time one person went through the turnstile the jack pushed the walls out. Theoretically, if enough people had visited the exhibition, the museum would have come crumbling down. And one of my very favorite works—something I consider incredibly beautiful—I saw at MOCA [Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles] in 1986. In the work Exposing the Foundations of the Museum, Chris literally dug down to the foundations to expose them, to expose the facts: the structure, the infrastructure, the truth of this thing of the museum.

In our collection at LACMA are the police uniforms, L.A.P.D. Uniform (1993), and another work, which was recently acquired thanks to a generous gift from Eli and Edythe Broad—half for LACMA and half for MOCA—the very beautiful Hell’s Gate (1998) bridge. And of course we have Urban Light. Before we delve into that work, I’d like to talk about some of Chris’s projects that are somewhat recent and that relate very much to some of the ideas found in Urban Light.

Chris BurdenA Tale of Two Cities, which actually premiered here at the County Museum in ’81, is a giant toy collection. It’s about a mythic sort of world where everything’s degenerated into city-states, sort of like Italy in the Renaissance. There are two cities: the big city and the little city, and the big city is invading the little city—you can see these giant robots marching out. The idea is that weaponries are purchased from foreign factories, or actually that the big city makes a lot of its own weapons. And the cities are actually surrounded by a stockade fence of bullets, actual real live bullets.

I think what’s very interesting about this sculpture for me was that it was acquired by the Newport Harbor Art Museum, and there’s a great contract which acknowledges that this is an ever-changing work and I have the right to change it in the future. I can add to it or subtract from it. I’ve never seen an art contract like that, where the artist has a right to go back in. So if there’s something I missed from my coin collection—

MGYou can add it or subtract it.

CB Yeah, I can add to or subtract from it. It’s a changing work and everything is loose. Nothing is glued down. So, all these things get wrapped up and put back in their crates.

MGIt’s worth talking about scale in your work.

I’ve needed architecture, too, to use as a foil for my art and to keep the rain off my friends’ paintings.

Chris Burden

CBThere is a certain scale in model railroading called “Z scale.” And the scale is 1 to 220. It’s very, very small. People are less than a quarter-inch high. A mile in Z scale is twenty-four feet. So I had this fantasy: it’s called Pizza City (1996) because I’ve had this idea that I could make a slice of the ideal city, which is one that you could walk out of in twenty minutes. So I started collecting buildings wherever I went, to fit this scale. And the idea is that it was a pizza shape because I couldn’t model a whole city but I could do a slice of one. The tip of the [slice] would be the harbor, then a downtown section, then apartments, suburbs, and then the crust of the mountains.

So I started collecting these buildings and had an assistant who would make them out of paper. We’d get all kinds of paper buildings and reduce them to the size. I collected for about seven years, and as it progressed I realized that I unwittingly made a model of Los Angeles, because the architectural style is all over the board. I mean, there’s a Tudor cottage next to a skyscraper. It was eventually acquired by a museum in Vienna called the MAK, and by that time it had grown to twenty-six tabletops and you could walk through it. There’s also a whole series of streetlights that go down it.

MgI know you’ve also had a great interest in monuments, or things that are big achievements of engineering and stand as monuments, like Another World I from ’92.

CBIt came from somebody who asked me what my favorite public art was, and I said the Eiffel Tower. Then I started thinking of, for example, [what] if Disney bought the Eiffel Tower, how they might improve upon it. Because the Eiffel Tower was a very hopeful thing at the turn of the century, and the Titanic was sort of the beginning of our disenchantment with technology—that it was a technological failure, actually—my idea was to build two twin Titanics and hang them off the Eiffel Tower, and people could board them.

MgIt seems like you have a strong feeling for monuments, not only how they embody a particular time in history but also how they change in their meaning.

CBYeah, they do. The Eiffel Tower was hated by the Parisians when it was first put up, and you can understand why. Before the Eiffel Tower, Paris basically had only five- or six-story buildings, and all of a sudden this monstrosity rears its head.

MGThis makes me think about what you’ve said about the lamps for Urban Light—that in their inception, those lamps were public art. They were expressions.

CBWell, they’re ornate beyond anything that’s necessary. And that’s how whole neighborhoods would be defined. They were actually used as a real estate come-on. I have pictures where you can see a bean field and then they put all the streetlights up. They were to tell you how and what kind of neighborhood you’d be moving into. So they were actually—

MGSigns.

CBYes, real estate signs.

MGWhat’s the difference between art and architecture in your work, as you think about your use of architecture?

CBI think art and architecture are very symbiotic. I think they need each other. I studied architecture a little bit in college, but I rejected architecture when I worked in an architectural firm one summer. This firm literally took up a seven-story building, and the partners in the firm were on the top floor and the lowest people were down drawing toilet bowls and plans and stuff. I was in the sub-subbasement organizing old magazines. So, it appeared to me that you had to be somewhere in your fifties before you got to make an architectural decision of any consequence. I don’t think that’s true now, but I did then. And I could go to the Sculpture Department at Pomona College, and in two or three months I could make a sculpture and it would be finished, and I had total control over it. That seemed a much more appealing route to [take]. But since then I’ve needed architecture, too, to use as a foil for my art and to keep the rain off my friends’ paintings.

One of the most beautiful lamps, I think, is called the Broadway Rose. There’s an artichoke in the finial, and also rosebuds. These lamps have a very interesting history…There are six of them in “Urban Light” and eleven of them left in Los Angeles.

Chris Burden

MGI think also that you seem to continue to be investigating what those primary issues are. I watched as you assembled Urban Light in a dense cluster in your studio and then you considered several options—lines or clusters. In essence what you created in front of the museum is architecture, right?

CBYeah, it’s a building with a roof of light.

MGAnd very specifically it’s like a temple. It is the museum temple, in that sense. Let’s talk about the making of Urban Light.

CBWell, this wasn’t something I planned to do. I’d been shopping at Home Depot, Home Club, those places, buying tape measures and whatever, and I had always seen that they had these aluminum knockoffs of old streetlamps. So one day I was walking around at the Rose Bowl Flea Market with my friend Paul Schimmel and his son, Max, and Max came running over and said, “Oh, you should check these out, Chris.” I went over and I saw two of these antique lamps spread in parts. I knew right away they were the real thing, but I asked the man, Jeff Levine, who was selling them, and he said, “Oh yeah, they’re genuine. They’re from the ’20s. You can buy them both. I’ll give you a real good price and I’ll deliver them.” I said, “Here’s a check. Great.” So, he brought them out and I said, “Do you have any more?” He says, “Yeah, I got four more like that.” I said, “Well, okay, I’ll buy those too.” Over the course of a year I bought about seventy of them he had in his backyard, all in this state of component parts. I lugged them all up to my place in Topanga, lugged them up the mountain. But he was still saving some of the really big ones he didn’t want to sell me. So I asked him, “Do other people collect these lamps too?”

Jeff had been collecting them for about twenty years, and he would go to the city when they were knocking them down. The city didn’t really care about them—most of them got taken to the landfill and thrown away—but he would go through all the broken parts. If there were twenty busted-up lamps he could salvage enough parts to make, maybe, three lamps. And he single-handedly moved all the stuff around. He’d gotten tired of being their caretaker. So when I asked him if other people collected them, because I wanted to buy more, he confessed he had another eighty-five stored. So we went through the whole process of having them sandblasted, powder-coated, all the hardware replaced with stainless steel or copper. It was a long process, and it was interesting. Jeff loves these lamps, so when he said to me, “I knew you would come someday,” I took that as a compliment, because he had made this huge collection and he really didn’t want to sell them off in twos or threes to homeowners to have in their driveways. He was hoping that somebody would show up who would keep his collection intact, and I was the guy. I still buy things from him to this very day. He’s a great collector himself, and he’s providing me with other goods. Through him I met a small group of lamp aficionados. They’re a small club. They’ve all known each other for twenty or thirty years and they swap parts.

One of the most beautiful lamps, I think, is called the Broadway Rose. There’s an artichoke in the finial, and also rosebuds. These lamps have a very interesting history. Their finials are very, very long, and for the first several years they were installed downtown. There are six of them in Urban Light and eleven of them left in Los Angeles. The reason for the long finials was that they predated the filament, the incandescent light bulb. They were carbon arc [lights]; a carbon arc has two carbon rods that are spaced slightly apart. You add a high voltage and there’s a huge spark. So the wick trimmer had to come every two or three days and crank the rod up to keep the right gap. So when you see streetlights with finials, those are all vestiges of a functioning finial, which initially these were.

you’ve assembled an honest-to-goodness Los Angeles temple of our own materials, made in our time.

Michael Govan

MGI know the MAK in Vienna had been interested in bringing these as an installation to Vienna. And it was actually Stephanie Barron, who is on our staff, who told me that I had to go up and see these lamps right away. I remember hustling up to see them and being incredibly amazed by them and knowing that they had to be in Los Angeles because in so many ways they were the representation of the whole county, with each city responsible for designing their own lamps. If you go and see the different forms of the lamps, you’ll see that each was an expression of that city’s design; they were public art.

CBYes, yes.

MGAnd, of course, they’ve now created this image of their density. You always knew they needed to be dense, right?

CBYeah, and you needed a repetition of form, too. It’s kind of like lining up toy soldiers—you know, where you get little columns of them. And I think the repetition works.

MGI have to say, when this model arrived and we had looked at this space in front of the museum, it was an instant eureka kind of moment, because these lamps had been assembled into a building, into architecture. And when you walk through the lamps, as you know, they have this feeling of a Roman colonnade or some kind of ancient structure. While they’re from the ’20s and they’re modern, they still have this feeling of walking through an ancient temple-like structure. And immediately it seemed to me this was the perfect image for the museum in Los Angeles, because all of those East Coast museums, even as far west as Chicago, stand with their Greco-Roman temple façades. That’s the sign that you’re walking into a museum—when you see the temple façade. And you think of that as being establishment. But, of course, this is a kind of faux temple. The reversal is there because those Greco-Roman temple façades are really faux; they’re neoclassical. And here you’ve assembled an honest-to-goodness Los Angeles temple of our own materials, made in our time.

I should also say that we were on a very tight deadline for this, and I had just arrived and, you know, hadn’t been here very long as museum director. Construction for our transformation was already proceeding, and we were trying to change a few things on the fly. Meanwhile, Vienna had articles in the paper about trying to raise the money to buy Urban Light, so we had asked our trustee Andy Gordon and his wife, Amy, to come see the lights in Topanga Canyon and help us decide how to proceed. On very short notice, under urgent pressure, they helped us decide that the work should be kept in Los Angeles. We acquired the piece and began planning its installation right away. Now it has become this incredible true landmark in Los Angeles.

In fact, I went on the Internet the other day and pulled up Flickr. There were, I think, 600 entries that came up under “Burden lamps LACMA.” People are out there every day taking photos of Urban Light. And in this new age of media and technology, these images of the lamps are going out all over the world and representing Los Angeles. You’ll see people getting out of their cars to capture it, lovers taking pictures under the lamps at night. People have been fascinated by the details.

Chris, you said that you saw the lamps as a statement about what constitutes a sophisticated society—“safe after dark and beautiful to behold”—which I thought was an incredibly beautiful statement. And I started thinking about that in relation to the history of all your work. People have written so much about your early performances, and they’ve even called them “cold and without morality”—for instance, in response to having yourself shot for Shoot. But I actually had the exact opposite reading, that somehow all of your work—whether shooting yourself or having others shoot you, your early performances, and the works that we’ve discussed here—has something to do with a sense of responsibility. Whether it’s you as an artist investigating those phenomena or thinking about the urban environment, there is some sense of what societal responsibility is. It seems to me that maybe your work has this arc that has held it all together. Do you feel that there is something beneath all of this that you can put your own finger on?

CBWell, I often think it’s about imagining something—something you might reject as being out of hand, initially—and then trying to look at the other side of the coin and seeing what that might be. I think there are often two ways to look at something.

This conversation was excerpted and slightly adapted from “The Director’s Series: Michael Govan in Conversation with Chris Burden,” a public conversation that took place at LACMA on December 17, 2008. Artwork © 2018 Chris Burden/licensed by The Chris Burden Estate and Artists Right Society (ARS), NY