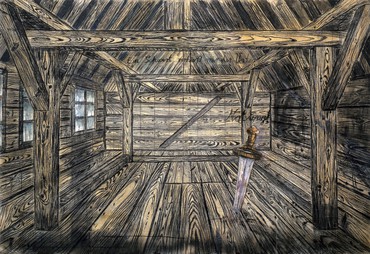

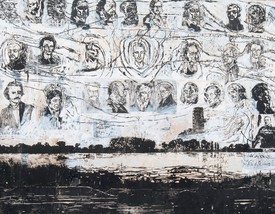

Anselm Kiefer’s monumental body of work represents a microcosm of collective memory, visually encapsulating a broad range of cultural, literary, and philosophical allusions as well as symbols from religion, mysticism, mythology, history, and poetry. Photo: Peter Rigaud, courtesy Shotview Syndication

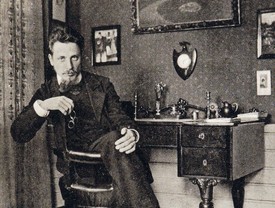

Tim Marlow is chief executive and director of the Design Museum, London. Formerly the artistic director of the Royal Academy of Arts and director of exhibitions at White Cube, both in London, Marlow is an art historian, curator, writer, and award-winning radio and television broadcaster. Photo: Cat Garcia

TIM MARLOWNow, I know you are not interested in academic history painting, but it seems to me that you are a history painter in the twenty-first century.

ANSELM KIEFERWell, I suppose it depends on how you define a “history painter”? For example, Meissonier and Defregger illustrated special moments in historic battles by making figurative and explicit paintings, but in my view that is very boring. So I am not a history painter in that sense. You could say that history is my material; I use it the same way that I use clay.

TMPerhaps that is how we define a history painter in the twenty-first century. Maybe that’s how history painting is in a post-photographic age, since the illustration of historic events no longer has a function for artists.

AKWell, there is a very big difference between painting and photography. A photograph captures a moment. Whereas a painting has layers; it’s more than a moment. It’s more than a year. It’s more than human time. It’s theological time, cosmic time even.

TMSometimes you use photography as a base in your paintings, and other times, there are no photographic elements at all. What’s the relationship?

AKWell, I also use photographs as material. In many ways photographs function as a sketch; I paint over it, destroy it, and then the painting emerges.

TMAs you get older do you find that making work gets easier or more difficult?

AKIt’s easier and it’s more difficult. It’s easier because if a painting is stuck, then I have established techniques for opening it up again, for example leaving it out in the sun or in the rain. There are certain methods that I return to over time. On the other hand, it’s more difficult because it can be challenging to create something completely contrary to what I’ve done before.

You could say that history is my material; I use it the same way that I use clay.

Anselm Kiefer

TMDo you have strategies that challenge you out of doing what is familiar or what seems easy? Do you try to make things difficult for yourself in the studio?

AKYes, I try. For example, last year I did very small watercolors. Making a watercolor is a completely different process—you make a work and you cannot correct it. When you make an oil painting, you can paint over it—in thirty years, you can paint over it but with watercolor, you have to decide in the moment. So it trained me to do something else.

TMThe exhibition will begin with watercolors. People seem very curious about your career, because you develop themes or series and then you seem to finish them, but you always return and things evolve or get reformulated. There’s often a connection to your earlier work. Do you have a sense of your career having a linear evolution? Of course typically that’s how we try to make sense of our own lives retrospectively, as a chronology of years, but then things are always more complicated than that.

AKMy thinking feels more circular, everything comes again. On another level, perhaps, everything comes again and again and again.

TMAre you seeking some sort of perfection with each work that you create?

AKI wouldn’t say perfection. I would say precision. It has to be as precise as it can be for the moment. And, yes, when I start something, I try to do it better than before.

A poem is like a diamond. It’s concentrated. It has an intense energy. It’s something you cannot find easily in the world. It’s erratic. It’s like a meteorite.

Anselm Kiefer

TMYou said recently that art is a quest for the truth. It can never be realized, but it gets close sometimes.

AKTruth is a difficult word. It’s a big word. For example, Heidegger, when he wrote about art, he wrote about art as truth, to search for truth. We can never achieve truth, there is no truth in the world—it doesn’t exist. If you shake things up as you make new connections, then you can find another kind of truth, and you can say that for this moment, this is perhaps the truth, but you have to understand that you will always lose it because the development will be that, in the end, there is no truth. It’s a big effort to find it.

TMSo is there an inevitable futility in what you do?

AKWe don’t know why we are here. We understand evolution, that 260 million years ago a meteorite killed ninety-seven percent of all life on Earth, and then evolution happened and now we are here. But we don’t know why. Who managed this? It’s amazing. And so, as an artist, you try to create some sense of truth.

TMIt’s a familiar idea that one of the primordial reasons why artists are compelled to make art, may be to make sense of the world. The other is to affirm the fact that they are here, that they exist. I’m interested in how you place yourself in your art. At the beginning of the exhibition, people will see beautiful self-portraits that you made, starting in watercolor. But you have returned to self-portraiture throughout your career, even though it’s not a dominant motif. People often want to read the artist’s personality into the work. Where do you sit in the broad body of your work? As a detached creator or someone embedded within it?

AKIt’s difficult to describe my position. Perhaps I am at a point where a lot of streams flow through, and some particles from the streams stay with me and provoke something, create something.

TMIn your recent lectures, one of the themes—and it was also a theme you mentioned in a speech you gave for a prize that you won in Germany a few years ago—you discussed the ideas of borders and boundaries. So let’s talk about borders, boundaries, and thresholds, because that was something that was important to you from childhood, wasn’t it?

AKYes, I’ve reflected about borders a lot, because for me it’s all illusion. A border is an illusion. For example, the skin is a border in a way, but there are particles from the cosmos that can pass through. Particles that pass through the Earth, even, and come out on the other side. Where I grew up was on the border of the Rhine. Our house was perhaps one or two kilometers from the Rhine. There was a dam and, in the spring, the Rhine would rise and suddenly our cellar would be flooded with water from the river. The Rhine was a border between France and Germany, and I remember thinking how the border moved through our cellar. That experience developed into an interest for borders.

TMThat’s wonderfully vivid, actually, that as a child you were told what the border was and then the border came to you. Did that seem absurd to you at the time?

AKNot at all. A child never thinks something is absurd. They take it like it is. They take it in and they don’t judge it. As a child we don’t reject things, we just let everything in, and once it’s there, it creates a new world.

TMIs your view of human spirituality a pluralistic one that is connected with a larger flow of energy or are there still traces of Catholicism in your spiritual makeup?

AKThe really best religion I’ve found is in India, Hinduism. When you tell someone that you want to be Hindu, they tell you, “Stay where you are, because each religion is as good as any other.” That is really wise, because there is no true religion, nobody knows what the truth is, the deeper truth.

TMDo you think some people treat art in the same way that they do religion?

AKNo, art is not the same as religion. Art does have mythology, and myths try to explain the world. Science can explain the world in pieces, but mythology tries to explain everything. So in this singular way, art overlaps with religion, but it is not the same.

TMSometimes when people call paintings poetic, it can be very nebulous, but there’s nothing nebulous about your work that involves poetry. What does poetry give you as a painter?

AKA poem is like a diamond. It’s concentrated. It has an intense energy. It’s something you cannot find easily in the world. It’s erratic. It’s like a meteorite.

TMWhat is the relationship between your work and Paul Celan or Bachmann? When you make a series inspired by their poetry, is it a kind of conversation?

AKYes, there is a real discussion with Ingeborg Bachmann, with Paul Celan, with other poets—Robert Musil. You could say that I’m asking them how they feel about what I’m doing. And it can be a hard conversation sometimes.

When you say “sublime,” it makes me think about music. In many ways music is more developed than art. Being a composer is more abstract, and more emotional even.

Anselm Kiefer

TMYour process of making art, it’s quite varied. You’ve made books, watercolors, paintings on a small and a very large scale, installations, sculptures . . . You’ve made an entire environment at Barjac! But if we might distill all of that, is the process of making art something that you find physically and emotionally immersive? Is it all-enveloping for you or is it more strategic? Are you stopping and looking and stopping and looking, or does it take over?

AKAt first it’s very direct, very emotional. I’m in synch with the material. When I reach a certain state in the painting, then often I go back and look, and there is a discussion with the painting about what happens next. But it’s always different.

TMYou have been known to leave paintings outside or approach them with flame throwers, or hosepipes, or axes. Is painting fundamentally violent for you? Is there a violent undertone in a lot of what you do?

AKThere is a war in my head all the time. After you start a painting, there is a certain time when you have to decide how to proceed, which direction should it take, and it can be difficult. With each decision you leave one hundred other possibilities behind and it’s impossible to know if you made the right choice. This struggle is evident in physical actions taken against the painting.

TMAre you interested in the sublime? Because this idea of awe or terror, and the violence of elemental forces, these are things that you’ve certainly harnessed. But is the sublime a sensation or sensibility that you’re interested in exploring?

AKWhen you say “sublime,” it makes me think about music. In many ways music is more developed than art. Being a composer is more abstract, and more emotional even.

TMWhat about the idea of trying to create environments? In Barjac, you create spaces that are self-contained and in which a single work of art is installed as a stand-alone installation.

AKYes, in Barjac the houses are like a skin around a painting or around a sculpture. A semipermeable skin.

TMDo different spaces fundamentally change the way you see your work? Is there typically a conversation between an exhibition space and your work or does your work dominate?

AKFor me it’s very interesting when my paintings are exhibited in other places—in a gallery or a museum—because once they are installed in another environment, they change. It’s also good for me to control them, to determine whether they are finished or not. Very often, during an installation, I will decide to take some paintings back, because that is when it becomes clear that they are not finished.

TMSo then it seems as though exhibiting doesn’t feel like an end, but rather part of the process, and actually in some ways makes you want to change or continue on the work?

AKYes. Yes, that’s absolutely right.

TMFor this retrospective, you made new work that reexplores work that you’ve made in the past in a conscious way, or did you forget that and make self-contained new work the same way you would for a show that was stand-alone, a show that only dealt with new work?

AKThe work I make now is always connected with what I made twenty, thirty, forty years ago. It’s always connected.

TM No, I understand that, what I mean is, did the process of trying to organize a retrospective make you think about your past in new ways? Or were you unaffected by the fact that you were working on a retrospective, and so you continued to work in ways you would have worked anyway?

AKAt first, it’s very boring to do a retrospective, because you are only revisiting your old paintings. But it’s an opportunity too, because you can see connections through the past forty or so. And you can create a new connection with something from forty years ago and perhaps learn something new.

TMWhat did you realistically hope to achieve with this exhibition, from a personal point of view? Is it part of a journey of learning?

AKI hope that the public and critics understand that I do much more than only big bombastic paintings, that I do other things too, that I’m involved in watercolors and books. Sixty percent of my work is books, you know, it always has been, even now.

Artwork © Anselm Kiefer; Anselm Kiefer, Royal Academy of Arts, London, September 27–December 14, 2014; this text is an excerpt from a longer conversation, held on April 1, 2014