Today’s golden age of rediscovery has truly embraced the spirit of the hunt, poring into art history books and poking into attics to resurrect and restore critical attention and acclaim to many unjustly neglected artists’ oeuvres and legacies. So it’s natural that one could assume a similar story line behind the career of the expansive and cerebral Japanese-American painter Arakawa.

But, as befits his always-surprising career, the story of Arakawa is no simple rediscovery of a neglected talent. In the first place, painting didn’t leave him—he left painting. Around 1990, Arakawa decided to shift his focus away from his art-making practice to work with his wife and longtime collaborator Madeline Gins on theoretical architecture projects. In the second place, this second act was like a second show all its own, producing ambitious, colorful, and mind-bending buildings like the Bioscleave House (aka Life Expanding Villa) they completed in East Hampton, NY, a decade ago (with a sculptural “floor” as uneven as an Alpine hike). Designed to rejuvenate the sensory system and reverse the aging process, this and other housing projects broke through many boundaries: not just of art, but architecture, philosophy, phenomenology, biology, domesticity, cognitive theory, and probably a dozen other realms still to be named.

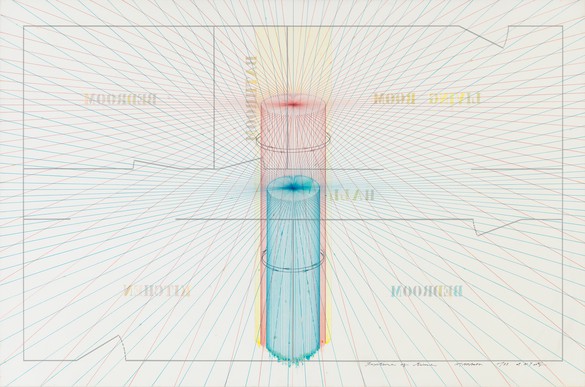

But to view the works in Arakawa: Six Paintings is to reconsider his overlooked legacy from its 1960s beginnings rather than its culmination. This is not an artist who forsook art for architecture, but an artist who reveled in accommodating, exploring, and reconciling the half-dozen or more art movements that were variously vying for supremacy in the ’60s and ’70s (and yet never epitomizing a single one). While only comprising six works, the show makes clear what an incredible hub of aesthetic and philosophical ideas Arakawa managed to represent in his painting, from the superficial visual elements to the abstruse theoretical concepts. From the Neo-Dada school, there are Rauschenberg-ian images and a sketchy, Twombly-esque aesthetic of ephemerality. There are the stenciled numbers and letters—present in Jasper Johns’s work as well as in proto-Pop artists like Larry Rivers and Robert Indiana. His work also dovetails neatly with the text-driven practices of conceptual artists like Joseph Kosuth and Lawrence Weiner (not to mention his fellow Japanese conceptualist Yoko Ono). And from Marcel Duchamp—an early champion soon after Arakawa arrived in New York from his native Japan in 1961—the painter absorbed provocative relational ideas about the essential nature of art as something experienced by a viewer.

Indeed, what’s so engrossing about the brief show is how deftly Arakawa manages so masterfully to weave together seemingly diverse movements into something that reads nonetheless as wholly authentic and unique. One 1971 canvas, From Mechanism of Meaning, merges freehand scribbling with a rigid conceptual framework to create an engagingly messy chart of more than two dozen ways to conceive of (or perceive) a lemon. (Some of the options: PAINTING OF A LEMON, LAST LEMON, MEMORY OF A LEMON, ACTUAL LEMON, HIDDEN LEMON, et al.) Other works merge, say, the conceptually scientific with the fancifully absurdist just as naturally, as if Arakawa was born to hybridize.

At the same time, the irony is that Arakawa is so formidably unique—arguably more unique than some artists to which he’s linked. But as visionary as he was, his layered aesthetic highlights a signal failure in today’s machinery of art appreciation: that is, its marked tendency to value artists that epitomize one singular practice or aesthetic over artists who function as hubs and connectors between movements and worlds.

That has been changing in the last decade, with the new engine of rediscovery having redirected critical focus to unorthodox artists the canon march left behind. That is the story here. Arakawa accommodated art, art didn’t accommodate him. From the look of this show, this time around it can and will. For a man who dreamt that art and architecture could somehow point the way to (if not deliver) eternal life, this overdue renaissance is a special kind of justice in more ways than one.

Artwork © 2017 Estate of Madeline Gins. Reproduced with permission of the Estate of Madeline Gins. Photos by Rob McKeever. Arakawa: Six Paintings at Gagosian West 24th Street, New York, May 2–26, 2017.