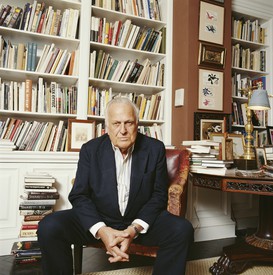

Derek Blasberg is a writer, fashion editor, and New York Times best-selling author. He has been with Gagosian since 2014, and is currently the executive editor of Gagosian Quarterly.

Derek BlasbergLet’s start at the beginning. Where did the idea for this show originate?

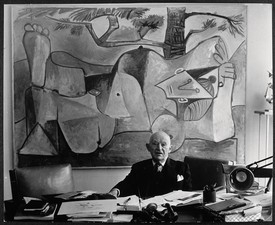

Dr. William JeffetWe had been thinking about it for a while, and as you know these ideas take time to develop. We noted years ago that there was a strong connection between Picasso and Dalí, and that their relationship—both personal and artistic—had manifested itself in different ways through the years. Dalí, of course, was younger than Picasso, and looked up to him.

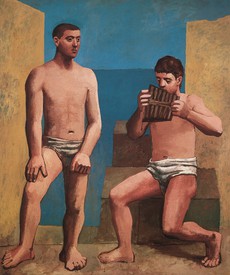

When Dalí made his first visit to Paris, in 1926, he visited Picasso in his studio, just before Picasso had his important solo show with Galerie Pierre Rosenberg. As there was a catalogue, and works from the studio were also published in Cahiers d’art, we have a good idea of what paintings the young Dalí saw on that visit. These included works such as Still Life With Antique Bust (1925) which we have borrowed from the Centre Pompidou.

DBWhy do you think that this type of show between these two artists has not been mounted often before?

WJFor one, I think when it comes to these two great artists, many of us have blinders on. These are great men, great artists, and they exist primarily in relation to themselves. Sometimes there are artists which have more obvious comparisons, like Dalí and the Surrealists, or Picasso and Matisse or Braque. This show is less obvious, but there are moments when there is a real proximity in their work, and this is surprising. Particularly in the 1920s, when Dalí first went to Paris and to Picasso’s studio, we can trace how Dalí went back to Spain afterward, and how Picasso’s work influenced his work. He is assimilating bits and pieces from that visit, and there are elements of Cubism and of Picasso’s playfulness from the mid 1920s evident. Not that it was a one-way street, either. Picasso began incorporating some surrealistic ideas into his work at that time. In the 1930s, when Dalí goes to live in Paris, they were both engaged in Surrealism, and often in group shows together, and doing covers for Minotaure, which was published by Skira. Skira, one of the great publishers of the day, also published Picasso’s livre d’artiste edition of Ovid’s Metamorphases, in 1931, and we are showing Dalí’s copy of this book. Skira then published Dalí’s livre d’artiste edition of Lautréamont’s Les Chants de Maldoror (1934), which was printed by Lacourière, who was also working with Picasso on the Suite Vollard, and other prints.

This wasn’t just a contextual show where we were looking for academic or documentary links. There’s a visual component here evident in the art, which supports what we’re trying to say.

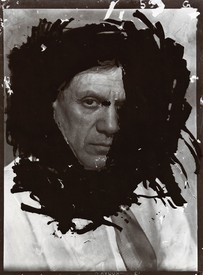

Dr. William Jeffett

DBI sometimes forget that in today’s digital age, an artist can see the work of another artist with the click of a mouse. But for Dalí to see Picasso’s work, he had to come up to Paris. How important was that trip to Paris in 1926?

WJThe pieces after that visit are quite different: some have even said it looks like that of another artist. It marked a transition. For example, after he went back he started using plaster heads in his still lives, which was very Picasso. This can be seen in Neo-Cubist Academy (1926) from the Museu de Montserrat, a really large painting that has rarely been seen in this country, or in Table in Front of the Sea (1926), an homage to Erik Satie, from the Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí. And then of course after Dalí moved to Paris in 1929 he again visited Picasso on numerous occasions, and their works were frequently shown together in group shows, especially those organized by the Surrealists.

DBDid they ever work on anything together?

WJThat’s a good question. We borrowed a “cadavre exquis” print from the Musée Picasso in Paris, which Dalí said he remembered making together with Picasso, but some Picasso scholars say they didn’t actually work on it simultaneously. It is a unique counter proof based on a Picasso plate, where there is both the Picasso composition and an intervention by Dalí. Dalí later recalled on two occasions that he and Picasso made it collaboratively one day when working in Lacourière’s print shop, but more recently Picasso scholars have challenged this assertion. At any rate, Picasso kept it and we have borrowed it from the Musée Picasso, Paris, as well as several postcards Dalí sent Picasso.

DBWhat was the most interesting thing you noticed when you were putting it together?

WJThat the paintings look good together. The pieces really complement each other, which I think says a lot about the artists and their works, for example Picasso’s Portrait of Olga, or Dalí’s Portrait of My Sister. This wasn’t just a contextual show where we were looking for academic or documentary links. There’s a visual component here evident in the art, which supports what we’re trying to say.

DBThey’re both dead, but in your estimation, do you reckon they were friendly?

WJI think there were moments when Dalí irritated Picasso, especially later on, but there must have also been a fondness there. For example Dalí and his wife Gala owned a 1913 collage by Picasso, which they gave to the Museu Picasso de Barcelona when it opened in 1963. Dalí spoke a lot about Picasso and Picasso famously didn’t talk about other artists much. But through the years, and primarily from the 1930s through the 60s, Dalí would send postcards to Picasso. We have a few in our show that we’ve borrowed from the Musée Picasso in Paris. Picasso didn’t directly remark on them, but the fact that he kept them says something. Also, it is worth mentioning that many were sent in the summer and bore the enigmatic local Cadaqués expression, “In July neither women nor snails.” Apparently Picasso looked forward to receiving these with relish.

This exhibition was organized by the Dalí Museum and the Museu Picasso, Barcelona, with the collaboration of the Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí and is supported by an indemnity from the US Federal Council on the Arts and the Humanities. Picasso/Dalí, Dalí/Picasso is on view at the Salvador Dalí Museum, St. Petersburg, FL, November 8–February 22, 2015

![Left: Salvador Dalí, Apparatus and Hand, 1927. Collection of The Dalí Museum, Inc., St. Petersburg, FL. © Salvador Dalí. Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, [Artist Rights Society (ARS)], 2014Right: Pablo Picasso, Femme dans un fauteuil rouge, 1929 © 2014 Estate of Pablo Picasso/ARS, NY/The Menil Collection, Houston, TX.](https://gagosian.com/media/images/quarterly/picasso-and-dali/OMO3LCrZpxfR_585x1170.jpg)