Derek Blasberg is a writer, fashion editor, and New York Times best-selling author. He has been with Gagosian since 2014, and is currently the executive editor of Gagosian Quarterly.

DEREK BLASBERGLet’s start at the beginning. Where were you born and where did you grow up?

NICHOLAS CULLINANI was born in Connecticut, and then, when I was four, my parents, who were British, moved back to Yorkshire.

DBWhen you think of your earliest formative art-world experiences, what comes to mind?

NcWhen I was a child, my parents took me to museums all the time. I remember being about nine years old and going to Manchester Art Gallery to see a Camille Corot exhibition. And we’d come to London for the Tate and the National Portrait Gallery, of course.

DBWas there an epiphany when you realized the art world or art scholarship was something that you wanted to spend your life doing?

NCYes, actually. I was on my gap year and trying to figure out what I wanted to do, and I ended up in one of the last rooms of the Galleria dell’Accademia in Venice with the cycle of narrative paintings by Carpaccio about Saint Ursula, which are still some of my favorite things, and which I always make a pilgrimage to when I go back to Venice. I remember it was a Wednesday night, and the gallery was closing, and I was sitting there with my guidebook studying these beautiful paintings. . . And I thought, “This is what I want to do for the rest of my life.” I committed to it right then.

DBVenice inspires everyone, but I guess especially you.

NCThe luckiest thing that can happen to someone is that they discover exactly what it is that they want to spend the rest of their life dedicated to, and let the rest flow from that. I knew in that moment that I would be completely happy with my decision—and thus far, that’s how it’s panned out.

DBSome people go to art school or work in a different industry altogether before landing at a museum. It looks like you’ve remained entirely in the academic space. Was that intentional?

NCI wish I could say so, but no, it wasn’t. I was basically focused on paying bills and being able to continue my studies. When I was earning my degrees, I needed to work, and I found paid internships and jobs at institutions, including the National Portrait Gallery. I know that if you look at my CV, it could appear as if I had this seamless trajectory—but I remember there were times when I was only a month or so away from not being able to pay my rent. The bigger point is that I was focused on my studies and art history, and I enjoyed those for their own sake. Only later did I realize museums would be my career.

DBWhat is it about the role of a museum that you find so dedicating?

NCAgain, it goes back to that epiphany in Venice: that day, I realized a museum can have a transformative experience, and that enjoying a work of art can improve someone’s life. Maybe they’ll just enjoy it for that moment—they don’t have to dedicate their lives to it like I did—but the effects can be quite clear and fulfilling. Wait. Do I sound like a cult leader?

DBNot entirely, but there could possibly be similarities drawn between the art worlds and a cult!

NCI knew early on what I wanted to do was study and work with artists and organize exhibitions. But what’s great about museums is how they relate to the public. It comes back to communication. Unlike the world of academia, museums aren’t necessarily preaching to the choir. It’s like when you discover something great, you want to pass it on. I’m that way with things like restaurants and music too.

I suppose I’m also a bit of a foreigner, like many of us, but I have a sense of belonging. And if you have that, you’re not threatened by the outside world.

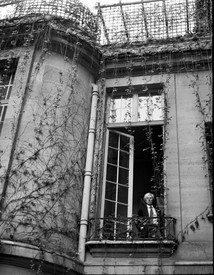

Nicholas Cullinan

DBThe Tate Modern’s Matisse cutouts show was a career high point, wasn’t it? How did that show happen?

NCI had worked with the Tate’s Nicholas Serota on a Cy Twombly show in 2008. Cy was still alive, and we would go and visit him and see his latest work still in the studio, which was incredible. And I’d think to myself, “This must have been what it was like to visit Matisse when he was working on his cutouts,” which he did toward the end of his life and in the South of France. Matisse would come up in conversation with Cy too. So, after Cy passed away [in 2011], things sort of happened organically. It’s like everything else that I’ve done: it’s intuition, not a master plan.

DBWas it difficult to make the Matisse show happen?

NCThe preconception was that it would be very difficult to get those loans. To be frank, we thought if we got forty or so pieces, we’d have done well. But it turned out to be surprisingly uncomplicated. Everyone was enthusiastic to be a part of this once-in-a-lifetime show, and we traveled and talked to lenders. I remember I went to the South of France and visited Matisse’s studio in Vence. Matisse’s view from his window was of a palm tree, which he painted several times, and when I looked at the same view, it was very poignant, as, sixty years later, the palm tree had grown too tall to be seen from Matisse’s window, but in its place were now two offspring. While I worked on the Matisse exhibition, Cy died, who for me had been the original inspiration. Maybe one of the reasons the Matisse exhibition did so well is because there was some emotional and personal investment behind it. I think the public can pick up on that.

DBI see that, in the history of the National Portrait Gallery, there’s only ever been twelve directors since it began in 1856. How does it feel to join that illustrious list?

NCI prefer to say “twelve to thirteen,” don’t you? Ha! And yes, it’s an honor to be on that list now. What’s particularly meaningful and exciting for me is that the National Portrait Gallery is an institution that I grew up going to, and then I worked here as a student, so I’ve spent a lot of time in these galleries. There’s some important personal symbolism in that, a connection between my own past and present. Yet, I also think that’s what this museum is particularly good at: providing a link from the historical to the present. There are over five centuries of portraits here.

DBThe museum’s charter says that the works only apply to British people—the sitter that is, not the artist. Is there anyone in the gallery that surprises you?

NCThe gallery breaks down in two ways: the collection is a visual history of Britain. Not every sitter has to be born and bred here, but they have to have made a contribution to British history. Then the exhibition program is about portraiture as a genre, which can cover any medium or period and, of course, be international. In terms of the collection, there are a few gaps that we are filling. Here’s a good example: we’ve just announced that our spring program will include the portraits of Howard Hodgkin, most of which are abstract. His work raises the very interesting question, “Does a portrait have to be figurative and look like the sitter, or can it instead capture the essence of them?”

DBMy first memory of the National Portrait Gallery was when I was studying abroad in London, and I came to Mario Testino’s show in 2001, which was a blockbuster. What are you looking for in your upcoming shows?

NCPhotography is a popular medium, and we do a lot with that. Earlier this year, we had the Vogue exhibition that looked at one hundred years of the British edition of the magazine, which was very successful. There are a few obvious ingredients in a popular exhibition: a recognizable name, and the general appetite right now tends more toward modern and contemporary art. But there is not a formula, and even if there was, I don’t think we’d want to follow it.

DBBecause you want to give people what they don’t know they want?

NCOne of the reasons I took this job is to make people excited about things they haven’t seen before. I want to communicate with a younger audience and introduce more people to historic art. That’s an important challenge for this gallery: what is British-ness now? What does this gallery mean during Brexit? We want to engage people in a discussion of how you can feel very much that you belong to a country, but retain an outward focus. I suppose I’m also a bit of a foreigner, like many of us, but I have a sense of belonging. And if you have that, you’re not threatened by the outside world.