Can you tell us about Ed Ruscha’s commission for the High Line in May?

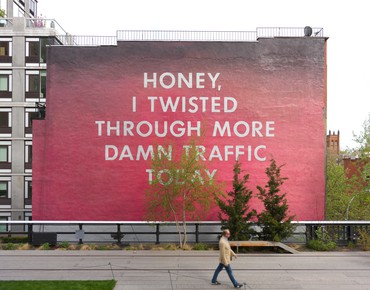

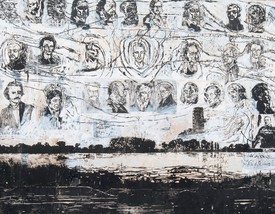

Cecilia AlemaniIt is the first time that Ed Ruscha is presenting his work in a public space in New York City. The project consists of a large-scale mural painted on the side of an apartment building overlooking the High Line at Twenty-Second Street. The mural recites “Honey, I Twisted Through More Damn Traffic Today,” and it is a reinterpretation of a 1977 pastel drawing bearing the same title. The mural is quite large, 30 by 50 feet.

What made you think of Ed Ruscha for this project?

CAMost of Ruscha’s work can be interpreted as a visual poem dedicated to the myth of the great American city. His parking lots and his views of Sunset Boulevard, his gas stations and even his recent paintings of industrial Los Angeles as transformed by the forces of globalization describe a personal geography—a psychogeography one could say—of which the American metropolis remains the main protagonist. His text paintings can be interpreted as fragments of the concrete poetry you encounter when driving across America, cutting and pasting in your mind the texts that pop up on billboards and signs along the highway. Strangely enough, for an artist who has so poignantly described our contemporary urban experience, Ruscha has never made a public work in New York City. He has made murals and public paintings in Los Angeles, Miami, Denver, and San Diego, but never here. That’s why I approached him and invited him to work on the High Line, which itself holds a very special place in the architecture and the imaginary of the city of New York.

How does this project specifically relate to the downtown neighborhood in which the High Line is situated?

CAThis project for the High Line combines Ruscha’s typical interests in architecture, language, and public space and creates a dry and humorous commentary on life in the contemporary metropolis. The High Line is certainly a very different environment from the cityscape of LA, but it is a quintessential urban experience that is deeply connected to the history of New York as an avant-garde hub for architecture and engineering, and to the multilayered lives of modern cities. The High Line is an elevated street that snakes through Chelsea and beyond, opening up hidden views and secret vistas. It was built at the end of the 1920s: it speaks of New York as the capital of the industrial twentieth century. Today, as a park, it connects to the postindustrial era of this new century. In these multiple stratifications, I think the High Line makes for the perfect background for Ruscha’s work.

What’s the relationship between Ruscha’s work and the High Line?

CAUnlike many other parks where you get lost, forgetting that the city is around you, the High Line is an urban park that makes you look at the city from a different perspective. Like many of Ruscha’s greatest works, this new commission both exalts and criticizes the romance of city life, instantly turning the urban experience into a dialogue worthy of a Hollywood comedy or a Jack Kerouac novel. Camouflaged in the architecture surrounding the High Line, Ruscha’s giant street sign reads like a speech bubble emanating directly from the streets of New York—a collective thought balloon hovering on the High Line like a silent soundtrack for a new symphony of the city. It is also an ironic take on the fact that the High Line can often be perceived as a very crowded location. The High Line is visited by thousands of people daily, almost like a pedestrian highway in the heart of the city. Here Ruscha’s work will reach the five million visitors who come every year to the park. Our public is extremely diverse: Chelsea art lovers, international tourists, New Yorkers who use the High Line for their daily commute . . . It is part of our mission to bring museum-quality works to a large audience, and make them available for free. Each viewer who will encounter Ruscha’s work on the High Line will bring a completely different and personal reading to it.

Who is going to paint the piece?

CAThe work will be painted by a company called Colossal Media, which specializes in hand-painted outdoor murals. You can see many ads around the city that have been painted by them: they are usually hyperrealistic murals on the sides of buildings. Colossal has also realized many other great artworks around town. They will be installing a swinging scaffold from the roof and from it a team of painters will be re-creating the drawing by hand. It will take a few days. Ruscha loved the idea of a professional company executing his work: since his early days, when he worked as a graphic designer, he has often found inspiration in mass media and commercial companies.

Ruscha and many of his contemporaries have taught us to embrace popular culture: with High Line Art we want popular culture to embrace contemporary art; we want to make art accessible to anyone, but without dumbing it down.

Cecilia Alemani

Can you talk about Ruscha’s previous public commissions?

CARuscha has done very few public commissions since the 1960s: they include outdoor murals for museums, large-scale indoor paintings for public libraries, and street billboards. A work that was very significant for me when I was thinking of approaching him was The Back of Hollywood, a giant billboard Ruscha did in 1976–77, commissioned by the Eyes and Ears Foundation. The billboard portrayed a reverse image of the Hollywood sign. Installed in a parking lot on Wilshire Boulevard, the billboard could be read accurately in the rearview mirror of a car—a motif that is recurrent in Ruscha’s work. Like many other works in Ruscha’s oeuvre, this image evoked eerie atmospheres à la film noir, with burning colors of the Los Angeles sunset and an odd, oblique angle on the famous sign itself, which exposed the scaffolding—and therefore the illusion—behind it. At High Line Art we have been commissioning artists to design billboards and we have presented a series of gigantic works displayed on a large billboard at Eighteenth Street and Tenth Avenue. We have shown works by John Baldessari, Gilbert & George, Paola Pivi, Allen Ruppersberg, and Anne Collier among many others. So to a certain extent Ruscha’s Hollywood billboard served as an inspiration for my program, but by inviting him to create a mural for the High Line, we wanted to propose a more long-term project. Usually our billboards stay up for one month only. Ruscha’s painting will be on view for one year: you will be able to see it as the vegetation and the landscape around it keep changing.

What do you think the High Line can offer more than a museum?

CAThe High Line is visited annually by some five million people, an audience that is comparable to that of the Museum of Modern Art. Unlike MoMA’s, our audience is mostly composed of people who are coming to the High Line for many different reasons other than the art. Our mission is to bring exceptional artists, like Ruscha, who you’d usually only see behind the closed door of a museum, to a large audience, free of charge. I think it’s our responsibility to show to a very diverse public that art should be part of our everyday life. Ruscha and many of his contemporaries have taught us to embrace popular culture: with High Line Art we want popular culture to embrace contemporary art; we want to make art accessible to anyone, but without dumbing it down.

How do you think High Line visitors will react to the mural?

CAOne thing that always amazes me on the High Line is to see how visitors react to the art. Some contemplate it, others just take pictures: for many visitors the artworks on the High Line represent a break in the usual experience of public space—a moment of reflection, interrogation, and enjoyment. In cities you are mostly pushed around and overwhelmed by the urban experience: on the High Line, with the help of art, we want to create a space where you are also able to engage with your own and with other people’s opinions.

Artwork © Ed Ruscha